Madeleine Arenivar on the Rhythm of Translation, Preserving Poetic Language, and Letting a Novel’s Voice Shine

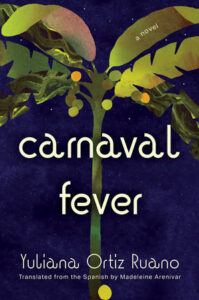

Lily Meyer in Conversation with the Translator of Yuliana Ortiz Ruano’s Debut Novel, Carnaval Fever

The translator Madeleine Arenivar, who lives in Quito, Ecuador, was a student in perhaps the most enjoyable class I’ve ever taught: an online translation course whose participants were, without exception, eager, gifted, and giving. We were unanimously delighted with Madeleine’s workshop contribution, an excerpt from the Ecuadorean writer Yuliana Ortiz Ruano’s debut novel Carnaval Fever. The book was already under contract at the time, and I’ve been waiting impatiently for its publication ever since.

I’m delighted to say that my wait is now over—and that Madeleine’s translation of Carnaval Fever more than lives up to the high expectations she created. Ortiz Ruano’s novel, in which a sheltered girl named Ainhoa describes a family and coming-of-age that she hardly understands, is at once casual and lyrical, detailed and dreamlike, joyously alive and shatteringly sad. I wolfed it down. You will, too.

*

Lily Meyer: How did you originally encounter Ortiz Ruano’s work?

Madeleine Arenivar: I went to one of her launch events here in Quito. I heard her speak and read from the book, and I just had a feeling right away. I just really wanted to translate it.

And then I read the book, and it was so incredible, I thought that someone would pick it up if I didn’t. I wanted to throw it out there, and so I did. I applied to the PEN Presents program from English PEN, which gave me a grant for the sample. That was a very positive experience—even the application is great in that it helps you reflect on the book not only in the world of translation but also in its original language, publishing scene, and culture.

This book is unique because it’s from Esmeraldas, Ecuador, which is the country’s only Black-majority province. It was its own kingdom, settled by escaped enslaved people from a ship that crashed on the shore, and then later it was incorporated into the Spanish colony. It’s always had a separate place within the country, due to racism and to structural issues of it being rather hard to get there from the highlands where the capital and the major cities are. And then it just has this really particular culture of orality and poetry. There are several nationally famous and somewhat internationally known poets from Esmeraldas in history.

Rhythm is so important. I read the whole book out loud, in Spanish and English, to really try and get the rhythm close.

LM: How did you approach translating both Blackness and provinciality when you are not Black and live in Quito?

MA: I am very lucky to have some family connections with Esmeraldas. I’ve been there, and Ainhoa’s grandmother’s voice sounded a lot like my husband’s grandmother’s voice. I also tried to immerse myself in Black literature and academic resources about Black English. Rather than try to mimic any American voice, though, I just tried to let the novel’s voices come through. I love what Kaiama Glover says about being in this in-between space and trying to get close to both the original and the English without necessarily being situated directly in one or the other. That really resonates with me.

LM: I thought you did an especially good job with your use of slang.

MA: I had a lot of fun. The book’s set in the 1990s, and so I was constantly looking up ’90s slang or trying to remember by listening to music—both the music that’s in the book and other ’90s music.

LM: Did that process also help you with the musicality of the prose? And how did you approach translating the song lyrics in the text?

MA: Yes. A local bookstore made a playlist of the book, which I listened to a ton when I was translating. Each song is linked to a specific part of the text and really influences the rhythm in that section. Rhythm is so important. I read the whole book out loud, in Spanish and English, to really try and get the rhythm close.

As to the lyrics—translating them was hard, but it was really, really fun. I really enjoyed it, and I just gave myself permission to do that. For example, the song that’s at the beginning of chapter nine is a traditional Colombian children’s song, and it just has this really fun rhythm. I felt especially free to play with it because as a traditional song, I’m sure that it’s changed over time, right? There’s not only one version.

LM: Can you talk about the Spanish you kept in the text? I’d especially love to hear about the words ñaña and ñañerío.

MA: I would never have translated ñaña—not because it’s an untranslatable word, but because it’s really a part of the story. It’s a word from Quichua, which is a language spoken mostly in the Highlands and some of the Amazon by indigenous people, but has a huge influence in the Spanish spoken in Ecuador in general. Ñaño means brother, ñaña sister, but in Esmeraldas, they use it to refer to aunts and uncles. Ainhoa briefly explains that in the book, and then it becomes a plot point when the protagonist’s cousins from Quito don’t understand why she’s calling her aunts ñaña. The aunts say, “It’s because we’re not old harpies. We’re young. We’re fun. We’re like sisters,” but it also speaks to non-nuclear kinship networks that communities form in Esmeraldas.

The language is very poetic throughout, but it heightens towards the end as the narrator is more confused and the situations are more opaque to her.

LM: What’s your relationship with the author like? How closely did you collaborate with her?

MA: She’s always been very available. She answered some important questions to help me fine-tune some important points towards the end. She’s very busy. She’s going to all the festivals and all the countries, but she’s always been super helpful and approachable. When I turned in the manuscript, she was the first person to reply to me, and she just said she loved it. That was the most important thing to me. If she loves it, then I’m happy.

LM: It’s not possible to talk about the plot of this book without ruining things, but there’s a big gap between what the narrator knows about her life and what we ultimately know—and the reader only becomes aware of that gap at the end of the book. How did you manage that reveal as a translator?

MA: When I first read the book, the second half gave me the feeling of a train going through tunnels, so that there are periods of blackness. I tried to maintain that feeling, to remember the choppiness between the scenes that starts to happen. The language is very poetic throughout, but it heightens towards the end as the narrator is more confused and the situations are more opaque to her.

And I was confused because of the poetic level of the language. There are some really strange images toward the end, and so even though I had translated three quarters of the book by that point, there were still parts where I had to throw out everything I’d translated before and just look at that page just for what it was to figure it out. In a way, that mimicked the protagonist’s experience of confusion and blackouts.

LM: Do you or Yuliana have any particular dreams about this book’s reception in the United States, or what readers it might find its way to?

MA: I think we’re both dreaming of prizes, not because we’re doing this for the prize, but because we think this book is just so incredible and we really believe in it. I also think not just about the mythical “English reader,” who we hear so much about in translation-world, but about Spanish speakers in the U.S. reading the English version who maybe never or don’t have the chance to get the Spanish version. It’ll be exciting to see what they think.

Mainly, though, I just hope this book is a breakout success, as it has been in Ecuador. I don’t even know what printing they’re up to.

LM: Where do you want to go as a translator after this?

MA: I mean, I just want to translate everything, anything I can get my hands on. Partially to learn and to get more experience in many different areas, but I’ve really fallen in love with it. It feels like a dream come true, although it feels silly to say that because it’s not like a dream that I’ve had for very long. It feels like such a joyful practice, and I just hope to do as much as I can.

__________________________________

Carnaval Fever by Yuliana Ortiz Ruano and translated by Madeleine Arenivar is available from Soft Skull Press, an imprint of Catapult Book Group.

Lily Meyer

Lily Meyer is a writer, translator, and critic. She is a contributing writer at the Atlantic, and her translations include Claudia Ulloa Donoso's story collections Little Bird and Ice for Martians. She lives in Washington, D.C.