Mad Men is leaving Netflix. Time to read John Cheever.

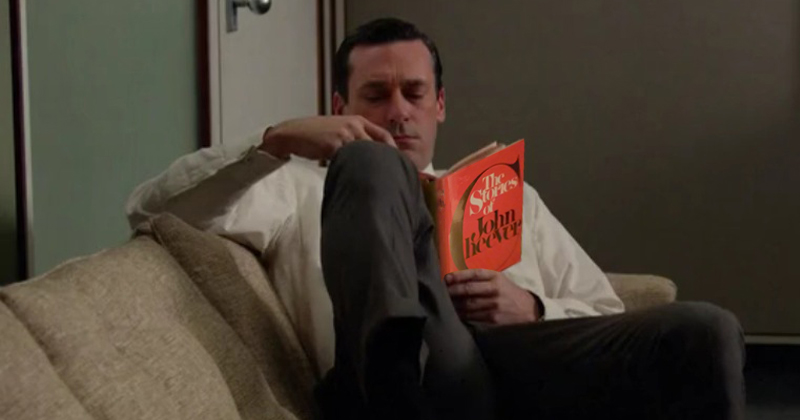

It’s official: on June 9th, the best TV show of the modern era is leaving the most reliable streaming service of the modern era. This is a harsh blow to the quarantined masses, whose reliance on the show during the time of COVID is well documented. In the scheme of things, I’m sure this will be a hiccup in the consumption of Matthew Weiner’s masterpiece. Given the known demand, soon we will surely be able to take on one more subscription and again be roaming the hallways of Sterling Cooper. But in the meantime, you might want to start planning to fill the Don Draper-shaped hole in your heart with the show’s narrative antecedent: the fiction of John Cheever.

Weiner’s fondness for Cheever is no secret, and though Cheever’s influence on the show is best understood in terms of tone and atmosphere, there are also some unmissable on-paper similarities between the late author and Don Draper, the protagonist of Mad Men. As Cheever did, Don Draper lives in Ossining, New York, and like Cheever, Draper’s reliance on alcohol warps his mind and damages his relationships. It may even be worth pointing out that the names “Don Draper” and “John Cheever” are phonetic cousins.

But in terms of storytelling, what Mad Men lifts most directly from Cheever is a tendency toward what is most often and most conveniently termed “enchanted realism.” One of the plainest examples of this in Mad Men comes in the Season 5 episode “Lady Lazarus,” when after seeing off his new wife, Don peers down an empty elevator shaft after the doors have mysteriously opened. We see the drop, we hear the whirring of machinery and air drafts, and as Don backs away we wonder right along with him what the hell just happened, and what it means. (If we’re too much like him, we also guzzle a stiff drink.)

So what does this image mean, or represent? Theories abound in the comments sections of any YouTube posting of this clip, and Matthew Weiner even once offered an explanation of it, but I’d say the simplest, most useful and perhaps most annoying answer is that it means whatever we want it to mean. Or maybe it’s better to say, do with it what you will. We know the character, we know the universe, and so from time to time we can fairly be saddled with some ambiguity. It’s an authorial provocation by way of a striking image, a method that the show trades on frequently, as does Cheever.

For example, Cheever ends his story “The Country Husband”—in which a man survives a plane crash and returns home to find his family pretty much uninterested in his ordeal—with this line: “Then it is dark; it is a night where kings in golden suits ride elephants over the mountains.” Its meaning is not immediately clear. How long ago did such nights occur, and in what country? I suppose Xerxes the god-king comes to mind, but if the details can be joined to any actual historical particulars, I’d argue that that is secondary, or altogether irrelevant. The important thing is what it evokes; in my mind’s eye I see the mountains, the elephants, the golden suits, and, reflected dimly in points off the golden suits, a purple-pink sunset. By this point, I have been convinced of a stable domestic world in which remarkable things occasionally happen, so rather than struggle against the narrator’s final flight of fancy, I am content to linger in the image and fill it in further. That is the true measure of Cheever’s prose, not that it is worthy of admiration (it is), but that it gets you to participate. Readers, like vampires, need to be invited in.

Both Cheever’s fiction and Weiner’s sometimes push the enchantment a step further, to memorable effect. Take the death of Bert Cooper in the mid-season finale of season 7. He passes away the night of the moon landing, and the next day in the office he serenades Don with a rendition of “The Best Things in Life Are Free.” Nobody else witnesses the sign-off (though surely some underling must see Mr. Draper just standing there looking at nothing for five minutes), and though it’s a poignant moment, it’s also one that runs contrary to everything we’ve been taught about Cooper. (RE things being free: his favorite author is Ayn Rand.) So again, as viewers, we are left to our own devices. Are we glimpsing Cooper’s true nature in a moment of transcendence, the one he was scared to divulge at work? Or is this an episode of alcoholic psychosis in a man who is about to once and for all lose the grip he has on his emotions? Or something else entirely?

Consumer’s choice.

Cheever manages a similar effect in his most iconic story, “The Swimmer.” Neddy Merrill resolves to leave a neighbor’s cocktail party to swim across the county by way of the local swimming pools. After each pool he stops, chats, has a drink with its owners, and the conversations become increasingly ominous, alluding to debts and fractures within his family about which he has no idea. He becomes confused, exhausted, and at the end Neddy is outside his own house, pounding on the door to be let in, but nobody is there. It could be that Neddy is very drunk and his family is simply not home yet, and it could equally be that the swimming pools have accrued to a portal across time and space. The mundane has run up against the inexplicable, and we are left to ponder.

After the visitation from Cooper’s ghost, I spoke to just as many people who hated as loved it, and I would never try to make the other side (hate) feel differently than they do. Similar reactions come up whenever I get into a conversation about Cheever’s work, which is a good thing. Consensus around art is dull. One of Cheever’s characters might have said it is dreadfully dull. You shouldn’t expect everyone to love what you make, you should only want them to stay until the end.

All this to say: if you find yourself dearly missing Don Draper and co. come June 10th, take twenty minutes out of your day and read a Cheever story. Unlike episodes of Mad Men, you can find them everywhere.