M.L. Rio on Writing Real Songs for Fictional Bands

“Too much granular detail can suck the life out of something.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

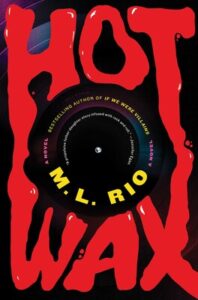

As any woman who’s ever worn a band T-shirt out of the house can attest, the proprietary indignation at perceived inauthenticity in the music space is so extreme it’s become a meme. (Recently, someone on Threads recommended that ladies respond to the evergreen “Name five songs” fandom purity test with “Name five women who trust you.”) Write about a band—even one that isn’t real—and the book will be held to the same impossible standards. One early reviewer panned my forthcoming novel, Hot Wax, for having the audacity to put music in print at all.

I can sympathize with the sentiment, to some extent; I’ve told my agent I’m not interested in selling film rights to Hot Wax because Hollywood almost always gets music movies embarrassingly wrong. I don’t feel the same about the written word, partly because I’ve been a rock critic myself and have a deep respect for music writing done well (it’s worth remembering that without publications like Rolling Stone and Creem and NME, your favorite rock stars would have languished in obscurity) and partly because I’m not afraid of a challenge in prose. That’s a good place to start, if you want to write a rock band worth reading about: you’ve got to have the gumption to put something essentially audio-visual down on paper in black and white, never mind the naysayers. And because the music industry is incredibly stingy with the rights to reprint lyrics, you’re going to have to write the songs yourself.

I have never been much of a poet, and no matter how well you describe the sound of the music itself or the spectacle of a live show, you can’t write your way around the words. Eventually you’re going to need lyrics.

In the nearly ten-year process of writing this book, I tried a lot of things that didn’t work and stumbled on a few that did. I talked to many musicians about how they approach the process, and unsurprisingly it’s as variable for them as it is for writers of fiction. Everyone’s methodology is different. One songwriter told me it takes him an average of ten years to write a song: some take twenty years to find their final form, while others erupt in full form in five minutes. I was strangely glad to hear it, because something similar happened to me. A few of the songs that survived to the final draft of Hot Wax were there at the beginning, evolving along with the book until I felt they were finally finished, but others jumped into my head so suddenly that they caught me completely by surprise. I once narrowly avoided being hit by a car in a crosswalk because a snippet of a song called “Handful” grabbed me by the hair and insisted I write it down, right fucking now.

What never worked was forcing it. I couldn’t just sit down and write lyrics the way I can just sit down and write prose after more than twenty years doing it. Unsexy as it sounds, what did work was a combination of research, character development, and patience. I learned to trust that the right words would find me at the right time, once I’d done the work to earn them.

A song like “Handful,” or “Minnie’s Place,” however instantaneous their composition and minimal their revision, did not come out of nowhere. Because of my academic background and my long, tiresome experience proving my expertise to men in the rock scene, my research for the book was exhaustive (but never exhausting, because you don’t spend a decade writing a book unless you love the subject matter intensely). I applied the same rigor to the songwriting.

Music, like literature, has genres and forms, recognizable patterns which signal to a listener, “This is a power ballad” or “This is a protest song” or “This is blues rock” or “This is hip-hop.” A single song can be many things at once, but it’s impossible to write one well if you don’t know what artistic traditions it’s descended from and participating in. So, much of the process of writing songs was actually listening to other songs in the same genre, made by the same kinds of bands, and studying how they worked: the structure of the music and how the lyrics mapped onto it. An eight-minute piece like “Stairway to Heaven” doesn’t have verses and a chorus but movements, almost like classical music; a tight three-minute pop single by Madonna will adhere to a stricter and more predictable structure. Once I had a handle on the overall shape of a piece of music, I wrote the lyrics out by hand and examined how they worked with it—diagramming them line by line, in a way I never have with prose. I needed to understand what I was trying to replicate in intimate, granular detail.

The beautiful thing about research like this is that the longer you spend immersed in it, the more at home you feel in the fictional world you’re building.

But too much granular detail can suck the life out of something. Good songs can’t be prefab or manufactured, no matter what the multi-billion-dollar corporations cannibalizing real art to train their AI would have us believe. Nothing so soulless could ever make your heart race or bring a tear to your eye the way real music does. And, for that matter, real fiction—which is where character development comes in.

Writing lyrics for a fictional band is a peculiar act of ventriloquism. You write songs not as yourself, but as a fictional character (or, in the case of Hot Wax, two fictional characters who are very different people). No two lyricists write lyrics the same way, just as no two novelists write novels the same way.

Character development has always been essential to my creative process, because I gravitate toward group stories where interpersonal dynamics matter more than any one person. To play fictional people off each other effectively, you need to effectively differentiate them so the reader can keep track of who’s who. Writing is an iceberg sort of art form where only 10% of the work ends up on the page; the other 90% includes excavating each character’s backstory. I start with where they enter the narrative and work backward through every significant event in their life until I arrive at their birth. Surprising discoveries abound along the way, and by the time I come back to the manuscript, each character feels more unique and more vividly alive.

But we’re more than just our biographies. One of the best writing exercises I was ever assigned in a workshop was to write a story about a character who never appeared on the page by simply describing a significant place from their life: their bedroom or their car, for instance. Our stuff says a lot about who we are and what we like. Each character of mine has a long biography, but also a bookshelf, a closet, a handbag, et cetera. In Hot Wax, they also had records.

No artist makes art out of nothing. We are the sum total of our unique creative pedigree, the myriad artistic influences which combine over time to give each of us a voice which is undeniably distinct. (At least, that’s the hope; idolize any one writer at the risk of sounding like a bad copycat.) Why should fictional characters be any different? Writing songs for my protagonist Gil meant I needed to understand not only his background, but the musical influences which shaped him as a songwriter and a performer. What was he listening to when he was learning to write? How was his taste molded by his life experience? He learned English mostly from the Bible but walked away from that life, so it was no great surprise that more than one of his songs takes a blasphemous turn. His early musical influences were mostly rockabilly; his later listening took detours through punk and glam and blues. Writing songs that sounded convincingly like him meant I had to cultivate a close relationship with all those influences, too.

The beautiful thing about research like this is that the longer you spend immersed in it, the more at home you feel in the fictional world you’re building. Gil found his voice at the same time I was finding mine. It had to grow and change to fit this ambitious, risky project. By the time I’d worked down to the last drafts, the songs, like everything else, came much more easily. It was a thrilling synchronicity. Hot Wax, like Gil and the Kills, took years to find its footing, but now that it’s found the right sound, I can’t hear it any other way. The whole thing sings. The lyrics are, at long last, here to stay.

_______________________________________

Hot Wax by M.L. Rio is available via Simon & Schuster.

M.L. Rio

M. L. Rio is the author of international bestseller and BookTok sensation If We Were Villains. She holds an MA in Shakespeare Studies from King's College London and Shakespeare's Globe and a PhD in early modern English literature from the University of Maryland, College Park. Her research explores representations of madness and mood disorder on the early modern stage. She lives in Washington, D. C. with too many books, too many records, and a mutt called Marlowe.