Lynn Hill on Conquering the Treacherous Climb Up El Capitan

“We would do whatever was necessary.”

If there’s one female rock climber that any climbing enthusiast can name, it is surely Lynn Hill. Lynn has been used as the preeminent example for generations of women to look up to and as the end to countless debates over whether women could ever really climb as hard as men. Men have undoubtedly admired her as well, as her accolades place her in the realm of the best climbers in the world—not just the best women, but the best, period.

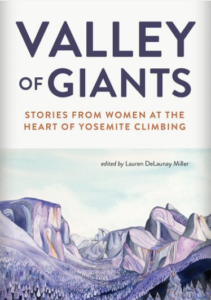

Lynn’s long climbing career is intimately connected with Yosemite, from her early years as a budding Stonemaster to her triumphant return to become the first climber to free climb the Nose of El Capitan. So when I set out to edit a collection of stories that would document the history of women’s climbing in Yosemite (what would become Valley of Giants), Lynn’s name was first on the list.

But she had so many notable ascents in the park, which story would I choose? Luckily for me, I was able to return to a book I’d read long ago as a new climber. I marked up my copy of Climbing Free: My Life in the Vertical Worldwith sticky notes so I could jump back and forth to the parts about Yosemite. At first, it seemed insane to not include the story of Lynn’s historic ascent of the Nose. It is, without doubt, the most well-known accomplishment of any female climber, both in Yosemite and likely in the world. But then, I thought, if it is already the most famous story, why repeat something that everyone already knows? If the goal of my collection was to show how underrepresented women have been in climbing history, did I not have an obligation to highlight the lesser-known stories?

Reading back through Lynn’s memoir, I was instantly struck by her recounting of climbing a route called the Shield with Mari Gingery. The two made the first all-female ascent of what was, in 1980, one of the most difficult aid routes on El Cap. I started casually asking friends in Yosemite—those who consider themselves diehards in the sport and troves of knowledge about its history—if they knew who had made the first all-female ascent of the Shield. No one did, and when I told them, they were surprised. Lynn’s legacy is largely focused on her free climbing prowess and athletic ability, so it seemed to me that her prominence on big wall aid routes had been largely overlooked.

At the end of this story, Lynn reflects on a quote from a prominent male climber in which he claims that women have been excluded from climbing history books simply because they were not present during the early years of the sport. But, as Lynn saw firsthand and as I learned through the process of editing this anthology, that just plainly isn’t true.

The vastness of Lynn’s accomplishments in Yosemite is proof to me of two important things. First, it is proof that even the world’s most famous female athletes rarely receive adequate recognition for the breadth of their experiences. And second, it is proof that women are, and have always been, central to the heart of Yosemite climbing.

–Lauren DeLaunay Miller, editor

*

This story is an edited excerpt from Lynn Hill’s memoir, Climbing Free: My Life in the Vertical World.

*

The Nose introduced Mari and me to the cult of El Capitan. Back then, on the cusp of the seventies and eighties, climbers viewed the experience of living for days on end on a gigantic cliff as a mystical pilgrimage. These were heady times. We indulged in these “vertical retreats” as a means of reaffirming our belief in the virtue of abandoning material comforts in favor of the kind of character-building experiences that inevitably occur on these big-wall journeys. Through such intense experiences you get to know your partner’s true nature without pretense. Mari and I were good friends and we worked well together.

This aspect of the sport is all about the mental space you occupy when you know there’s no turning back.

The Nose had provided a good challenge for us and we wanted more, so we planned another El Cap route. This time we’d do one that was steeper, more difficult, and that would require us to learn more advanced aid climbing techniques. This time we’d spend more time living in the vertical world. If Yosemite Valley is to the world of rock climbing what the Himalayan Range is to mountaineering, then for us, doing El Capitan by a route like the Shield would be the equivalent of tackling Everest.

The Shield is a big-wall experience altogether different from the Nose. While the Nose is steep, especially in the upper third of the route in the huge corners, the Shield is so overhanging that a drop of water falling from the top of the route would land in the forest 200 feet out from the base. The last chunk of the climb—a thousand-foot feature known as the headwall—juts over the floor of the valley so dramatically that the first time I watched a party climbing up it, I was reminded of two flies crawling around the underside of a giant hot-air balloon. The only way to climb this overhanging wall is by slow and methodical aid climbing tactics. Up on the Nose, Mari and I had often been able to stuff our hands into cracks and quickly free climb long sections of the route. But the cracks of the Shield are not much wider than a piece of string.

Into these we’d have to hammer tiny pitons, one after another for hundreds of feet. Hanging from our pitons in ladderlike slings called aiders and inching our way upward, it could take hours to climb 100 feet. Though I was more enthusiastic about the natural movement of free climbing, the dramatic, wildly exposed position that we’d put ourselves into on the Shield made the labor of aid climbing—which I have no interest in if taken as a style on its own—seem worth the effort. Aid climbing would take us to a place on El Cap that no other method would allow us to reach.

The other aspect of climbing the Shield that would be a new experience for us was the way we would have to live on the wall. On the Nose we found spacious ledges to sleep on each night. The Shield offered no ledges until the top. Instead we’d have to take our own portable ledges for sleeping on, which we’d suspend from the belays on the overhanging wall. Sleeping, eating, climbing, even answering calls of nature, would all be done in an overhanging environment. We were entering the arena of hard-core big-wall climbing.

To say we were apprehensive about doing a climb as wild as the Shield was an understatement. But once the work began, there was no more time to be nervous. At that stage in our climbing every experience was new, so we were used to finding new ways to adapt to whatever situation we were in. We always seemed to find a way to make it work. On the Shield, we would just have to find a way. Once we climbed onto the headwall, we would have no choice about backing off; rappelling back down such an overhang becomes nearly impossible because the rope swings free from the rock. So once we passed this landmark we knew we were committed. More common to mountaineering, this aspect of the sport is all about the mental space you occupy when you know there’s no turning back.

Prior to setting off we learned that two other teams wanted to jump on the route too—Randy Leavitt and Gary Zachar, both Californians, and another team from Arizona. Both teams had a wealth of big-wall experience under their belts. We agreed to let these all-male parties step in line ahead of us, and we stalled our departure for a couple of days. We figured that letting the faster, wall-hardened climbers go first was the “gentlemanly” thing to do. We were surprised to see, on our first day on the wall, both teams rappel past us on their way down. First Randy and Gary came down because Randy had gotten a splinter of metal in his eye, then the team from Arizona followed.

“What’s wrong? Why are you retreating?” I shouted up to one of the Arizona climbers above me. I wondered if the storm of the century was bearing down on Yosemite. Yet the sky was blue.

“We heard someone take one hell of a fall early this morning. There was a terrible scream. He must be way fucked up, or dead. It kinda freaked us out, so we decided to bail,” came the reply.

Mari and I eyed each other, then explained the story behind this bloodcurdling scream. Mari’s boyfriend, Mike Lechlinski, and Yabo [John Yablonsky] had set off at midnight to climb the 3,000-foot-long Triple Direct on El Cap in a day. When Mari and I arrived at the parking area below El Cap early that morning and saw the two of them standing by their car, we knew something had gone wrong. Mike was arranging their gear while Yabo leaned against the fender, smoking a cigarette, staring into the forest.

“What happened?” Mari asked.

“Yabo took an eighty footer!” Mike shot back.

At this Yabo uttered one of the staccato sniggers he was known to emit whenever nervous or unsure of himself.

“Yabo, are you okay?” I asked, looking him up and down from head to toe, searching for blood or bruises. He appeared unscathed.

“Yeah, I’m fine. I was climbing in my tennis shoes since it was easy up there. I was climbing with a pack and a full rack of gear, but I didn’t bother to put in any protection. It was four thirty in the morning, so it was a bit hard to see. I was cruising fast until I was nearly at the top of the pitch, and suddenly I realized that I messed up my hand sequence. Just then my foot popped off the face and I took a huge whipper,” came his sheepish admission.

“He was a hundred feet up, on the tenth pitch!” exclaimed Mike. “When I saw him flying through the air, I reeled in slack through the belay device, but I could see he had no pro between me and him. I thought for sure, we’re dead, he’s gonna rip us off the wall. Strawberry jam, here we come. But then his rope hooked around a mysterious knob or feature just barely big enough to catch Yabo’s fall. If he had fallen 10 feet farther, he would have come crashing down onto Mammoth Terraces. As soon as Yabo scrambled back down the last few feet onto the ledge, I flipped the rope and it came tumbling back down! I don’t know how the rope snagged on that chunk of rock, but if it hadn’t, Yabo would have gone another 80 feet! I knew Yabo was not badly hurt when he said, ‘Let’s go for it. We can do it.’”

The Shield was still there, though, awaiting Mari and me, so after hugging the boys and saying goodbye, we started jumaring up our ropes to Heart Ledge, where we had fixed them a few days earlier. Now that the last of the men had retreated due to the horror of Yabo’s primal scream, we had the wall to ourselves. It amused us to know that despite the more impressive range of experience that these teams had over us, we remained the determined ones, going to the top.

“A wall without balls,” I jokingly said to Mari, referring to the term Bev Johnson and Sibylle Hechtel had coined when they did the first all-female ascent of the Triple Direct on El Cap in 1973. The Shield, which loomed frighteningly steep over our heads, was now the sole domain of two women.

*

For the first two days of the climb we inched up El Cap’s glacier-cut face, slowly gaining height by the unfamiliar mode of aid climbing, and even more slowly dragging up our haul bag. For good reason, climbers refer to the haul bag as the “pig.” Haul bags are heavy, unruly, and obnoxious, and they do not obey. They often get stuck behind a flake or small roof and stubbornly refuse to budge. Whenever our haul bag got stuck, one of us would have to rappel down to the bag and maneuver it around the obstacle, then herd it upward. Ours was loaded with so much equipment, water, and food that it outweighed both of us combined. So on the first few hundred feet of the wall, Mari and I rigged a two-person hauling system. We each pulled out backward with all our might on the haul line, winching the bag’s weight through a small pulley. Our pig crawled up the wall in small surges. Our skin was rubbed raw from pulling on the rope. Sweat poured out of us.

After two days on the wall, we became accustomed to living in a reality where survival required us to concentrate on each move and to evaluate the consequences of every action, whether it was hammering in a piton or clipping ourselves into our batlike hanging bivouacs. During those intense moments of total engagement, I would become acutely aware of that little voice of intuition that on the ground is so often obscured by the clutter and command of our day-to-day thinking. On the sixteenth pitch off the ground, while bashing a piton into an expanding crack (a crack that opens as the piton is driven deeper into it, making for a very unstable piton placement), the thought occurred to me that perhaps I should have hammered this piton a little harder. In the next instant, after I had clipped my little 4-foot-long ladder of nylon webbing onto the piton and stood up in it, the piton ripped out with a loud ping. I flew 30 feet backward before a well-placed piece of gear caught me on the rope. The fall was over in less than a breath but the memory of the need to listen to the quiet internal voice of warning was never forgotten.

Night was a precious time when we could relax, eat, drink, and gaze up at the stars—but only after we had fiddled for an hour rigging and suspending our sleeping bunks. Mari had it good—she owned one of the first portaledges ever made. This newfangled gadget was a six-pound collapsible cot consisting of an aluminum frame strung with a nylon sheet. It hung from six webbing straps all sewn together into a single loop, into which she clipped the anchor. It made a comfortable sailor-style bunk. My bed wasn’t so deluxe. It was a banana-shaped hammock in which I slumped like a caterpillar in a cocoon. My first night in this was dire. In the corner of a dihedral, I hung in a bent position all night long, shifting from side to side in discomfort.

On the fourth day Mari led us up to the headwall. The pitch she followed to get us there was dubbed the Shield Roof, and it was indeed a giant of a roof. Hanging upside down under the roof to place each piece of gear, she dangled in her aid ladders, whacking in pitons and placing nuts whenever possible. Among the more dubious devices she hung her body from were “copperheads.” These are blobs of copper clamped onto the end of a thin wire cable, and they are used whenever the crack is too shallow to accept the blade of a piton. The copper blob is pounded with the pick of the hammer until it softens and molds around the irregularities of the crack. It then has the adhesive quality of a piece of duct tape, and you can hang a while on it before it gives up its grip and pops out. If you find yourself placing a lot of copperheads in a row, you know you are headed into territory with high potential for a big fall.

Our sport back then was directed by a fraternity of men … Yet women climbers were out there.

Hours passed while Mari led to the end of the Shield Roof. Finally shouting down through the afternoon wind that blew our hanging rope in a swirling dance, she let me know that she was off belay. I jumared up while removing a few precarious-looking copperhead placements she had hammered in. When I pulled around from the underside of the ceiling and joined Mari at the lip of the roof and at the start of the headwall, I found that we were poised in an outrageous position. Under our feet, there was nothing but air. Above us rose 1,000 feet of smooth, overhanging orange granite. To either side of us the walls curved around out of sight. We seemed to be suspended on the edge of the world, and the two of us and our pig hung from three steel bolts the length, yet not quite the thickness, of a half-smoked cigarette. Feeling vulnerable, I instinctively checked the knot at my waist, the only thing securing me to the anchor. I could see now why this climb had been named the Shield: the feature we were on resembled the curving shield of a warrior.

We had reached the point of no return. It would be impossible to rappel down from here. It was now summit or bust. But we grew accustomed to the exposure of our perch, and once we set up our portaledge and hammock for another bivouac, the calm of twilight descended and Mari and I were finally able to rest. A distant strip of clouds in the west, over the plains of the San Joaquin Valley, glowed with brilliant colors. Hanging side by side in our bivouac cocoons, we munched bagels, tuna, and canned peaches to add hydration to our dry pemmican bars that were loaded with calories. We had no fear of the height, only an enhanced sense of intimacy between us. Up here in this giddy place I felt as if we were the last people left on earth and secrets were of no use.

Our progress slowed to a snail’s pace as we coped with the difficulties of the headwall. Poking out of the crack ahead of me were occasional RURPs that had been hammered in so tightly by other ascents that they could not be removed. Old and tattered bits of skinny webbing tied to these “fixed” RURPs flapped in the breeze. These little slings creaked like ripping fabric when I hung from them. They felt ready to break, so I hurried on to the next placement. The only thing in my favor was that my weight—around a hundred pounds—exerted less force on the RURPs than other climbers. The more solidly built Charlie Porter, or any other guy who had climbed the route since him, likely weighed nearly twice as much as me.

On the fifth day we exited the headwall, hauling onto a large, sloping rock platform called Chickenhead Ledge, so named for the black knobs of intrusive diorite that poke through the bed of white granite. Sometimes these bumps resemble a head with a narrow neck, and some wit in the climbing world had likened the grabbing of them to strangling a chicken. With only one day left before we topped out, we slept well here, knowing we’d be on flat earth by the next afternoon. Some of our pitches had taken us five hours to lead. I wondered if I would bother doing another big “nailing,” or piton-bashing route, ever again. It was so slow and tedious and I missed being able to walk around and sleep on a flat, horizontal surface! We’d later learn that in the time it took us to lead three pitches on the headwall, Mari’s boyfriend, Mike Lechlinski, with John Bachar, had climbed all thirty-three pitches of the Nose!

We also learned that the guys in Camp 4 who knew us “girls” were up on the Shield and were occasionally checking our progress from the meadow below, had all made bets about when Mari and I would retreat from the wall, as the other two teams of men did. But Mari and I believed in ourselves and were willing to “put our backs into it,” as Mari liked to say. We would do whatever was necessary to get the job done!

The next day—our sixth since leaving the valley floor—we pulled over the edge of El Cap. Twenty-nine pitches lay behind us. The relief of the climb being over and the elation of finally standing on top was enhanced by the presence of John Long, otherwise known as Largo, and Mike, who had hiked to meet us on top, just as Mari and I had done when our boyfriends had reached the top of the Shield. In fact, that was when Largo had suggested that Mari and I climb this route together. After hearing about what a sensational climb it was, Mari and I had looked at each other and said, “Yeah, why not? Let’s go for it.” Though it was a lot of work, living in such a spectacular vertical world had been well worth the effort. Weighed down by our haul bag and by coils of ropes and racks of pitons, we wobbled on our legs, but we were grateful to be able to walk again and return to the comforts of a hot shower and some fresh food.

I had learned early on as a little girl that what I believed was appropriate or even possible was dependent on me: not on what others projected onto me because of my gender or appearances.

Years later, after I had done the first free ascent of the Nose, and then again in one day, I had read with some chagrin in Galen Rowell’s book The Vertical World of Yosemite, “Women are conspicuously absent from the climbs in this book. I have no apology to make here because it is not my place to change history. There simply were no major first ascents in Yosemite done by women during the formative years of the sport.”

Our sport back then was directed by a fraternity of men, and there was little encouragement or, frankly, inclination for women to participate. Yet women climbers were out there. There were women such as Beverly Johnson before me, who had done the first ascent of a big-wall route on El Capitan with Charlie Porter, the same person who also did the first ascent of the Shield. The fact that this woman who had done the first ascent of a big-wall route in Yosemite back then was not given credit or even an acknowledgment during those times was disgraceful to me. It was very important for me and others to know that there were other women out there who shared a passion for climbing and adventure.

I had learned early on as a little girl that what I believed was appropriate or even possible was dependent on me: not on what others projected onto me because of my gender or appearances. In fact, these types of stereotypic experiences throughout my life have become a dominant theme of my career. The underlying motivation for my most noteworthy ascents was that I felt the need to demonstrate that women can do whatever we set our minds to. Believing in ourselves is the most important quality of all. It’s amazing what we can do when we put our heart, mind, and soul into it to achieve something much greater than ourselves.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Valley of Giants: Stories from Women at the Heart of Yosemite Climbing edited by Lauren DeLaunay Miller (April 2022) with permission from the publisher Mountaineers Books. All rights reserved.

Lynn Hill

A natural athlete, Lynn Hill competed as a gymnast and runner and immediately excelled at rock climbing after roping up at the age of fourteen. By the late 1970s, she was climbing near the top standards of the day. After pushing the limits of sport climbing and succeeding on the world competition climbing stage, Lynn returned to Yosemite to complete the climbs she is undoubtedly most famous for: the first free ascent and the first free one-day ascent of the Nose on El Capitan, feats that changed the definition of what’s possible in rock climbing. Lynn’s climbing spans all disciplines: she was the first woman to climb Midnight Lightning, a very difficult bouldering problem, as well as the first to succeed on difficult aid climbs on El Capitan. There are few Yosemite walls Lynn has not transformed. She lives in Boulder, Colorado, where she climbs, guides, coaches, skate skis, and is raising her son, Owen.