Luz Aguirre on Living Inside the Panopticon as an Undocumented American

“We grow up in this country, immersed in this culture, without the tools necessary to fulfill unattainable ideas of prosperity.”

I came to the United States in 1990, when Americans believed that the worst of racism had been left behind. “Americans do not see color” was the standard saying of the day. I was sixteen years old when I entered a department store located in Lower Manhattan. I asked for a manager and was surprised that he was white, unlike all the other workers on the floor who were people of color. As I waited in line at the register, I could see that all the cashiers’ faces showed signs of exhaustion, lack of sleep, and overall stress. It was easy to make the connection to racism.

After that, I could see it everywhere. Wherever there are menial, low-paying jobs, people of color are doing them. How can white people not see it? It is perhaps the subconscious—or conscious—idea of white supremacy that, supposedly, people of color are where we are because we are not as intellectually capable as white people.

Even with that, I could never have imagined the xenophobia that permeates the American landscape in 2022. Some people blame it on the events of 9/11. I have always believed that 9/11 was used as an excuse to ramp up the exclusion of people of color in this country built on the backs of Black people and the near extermination of Indigenous peoples. An immigration reform seems farther away than ever since my transplant into the United States.

Yet “immigrate” is a term that I am not comfortable with. It seems too agentic, I was eleven and not part of the decision making on whether to come or not.

Sometimes, I feel that we spend too much energy discussing terminologies. Yet “immigrate” is a term that I am not comfortable with. It seems too agentic, I was eleven and not part of the decision making on whether to come or not. Some terms, like the use of “undocumented Americans” rather than simply “undocumented,” seems to catch the essence of our experience. We grow up in this country, immersed in this culture, without the tools necessary to fulfill unattainable ideas of prosperity and upwards mobility—we are told—”if only we work hard enough.”

When I was in high school, I longed to go to college, to have a “normal” American life. I disclosed my status to the guidance counselor. It was then I understood the precariousness of my legal situation. She said—full of contempt—that I did not qualify for college. This was not true. All I had to do was get enough money to pay for classes ahead of time, which is hard but not impossible. What I cannot do is apply for a job, an apartment, a loan—I cannot even apply for a magazine giveaway or a cooking show contest (Nailed It!, I am looking at you). You try keeping your dreams alive with so many no’s. The talk with the guidance counselor was the first time I had a sickly feeling. It is as if I am forever falling in space. My insides have a consciousness of their own and refuse to accept my body’s inability to anchor them to the bottom of my stomach.

For many undocumented Americans, the sickly feeling pops up when faced with the need to disclose status to someone who might not be receptive or familiar with the legal pitfalls of interacting on a professional level. I would give almost anything not to feel that way again. This is one of the things I blame for my clinical depression. Disclosing my status for a job with someone who holds my success and economic stability in their hands is almost impossible.

Many activists write about the need for undocumented Americans to build support networks which could open seemingly hermetically sealed opportunities and to avoid falling into exploitative situations, yet many of us are unable to do this. I grew up without my parents in violent environments. My mother migrated when I was four, my father abandoned the family. We were left under the care of people who saw my brothers and I as a burden. Violence at such a young age from people who are supposed to be your caretakers makes you unable to trust anyone and incapable of asking for help. The sickly feeling creeps here again.

Disclosing my status for a job with someone who holds my success and economic stability in their hands is almost impossible.

At 25, I was volunteering at a cultural organization. The executive director, impressed by how fast I was learning, wanted to hire me. I had to disclose. She took me to see a lawyer to find a way to get paid. The lawyer suggested I create an LLC which allows me to get paid as a contractor or freelancer. The ED became part of my support network but asking her for anything after that is physically impossible—sickly feeling, sickly feeling, sickly feeling—it is an illness at this point. It does not matter that I went from volunteer to program director without an education. Or from LaGuardia Community College to Brown University when I finally seeked an education at the age of 35.

The activist Jose Antonio Vargas has written about how undocumented Americans must excel if we want to get ahead but also stay under the radar to keep ourselves safe. Most of the time I feel completely exposed, I cannot see in front of me. I do not know when or to whom I can disclose my status.

The philosopher Jeremy Bentham called panopticon a structure from which others have the power to monitor you at any or all times—the ones being observed aren’t aware when they are being watched. The US immigration system knows I am here. I shudder to think where my information is stored within the government apparatus and for what purpose.

The writer and activist Karla Cornejo Villavicencio wrote that growing up, she felt admiration towards the self-made character Gatsby. My Gatsby was Vincent Freeman from the 1997 film Gattaca.

It is uncanny how much Freeman’s legal problems in this fictional world mirror the ones of real undocumented Americans.

In this dystopian film, most people are screened before birth for genetic abnormalities. Freeman’s parents could not have foreseen at the time of his conception that choosing not to screen would doom him to a marginal existence. He is born with a heart condition, therefore deemed an ”in-valid,” limited to accessing only menial jobs. He dreams of going to space and becomes a janitor in a NASA-like corporation.

It is uncanny how much Freeman’s legal problems in this fictional world mirror the ones of real undocumented Americans, except that legally, we cannot even hold menial jobs. He does not give up; he lies, cheats and is in contact with shady characters who provide him with phony documentation and bodily waste. He needs blood to enter the building, urine to show his fitness, hair to leave behind to avoid suspicion. He concocts ways to get around society’s panopticon which could expose him at any one time.

I have a hard time lying. I grew up Catholic which carries within it Aristotle’s ideas of creation of virtuous individuals through a list of actions that are either intrinsically good or intrinsically bad; lying is bad. For the philosopher Immanuel Kant, no lie can be justified because reasoning is what makes us human and lying makes our ability to reason a very murky business.

Like Vargas, Cornejo Villavicencio, and the fictional Freeman, I keep reaching for excellence while, as Freeman puts it, “refusing to accept the hand [I] was dealt.” As a non-religious person, I believe that this life is the only one I have. I want to look back at the end of it without regrets. Whenever I feel despair, I think of everything that happened for me to exist in this time and space. Life is incredibly valuable and unbelievably random.

The universe is supposedly around thirteen billion years old, the earth four and a half. Around three billion years ago, the first unicellular organism came into existence. Only six hundred million years ago, the first multicellular organism arose. According to science, the first modern humans can be traced to only three hundred thousand years ago.

Somewhere along the way, my ancestors managed to pass on their DNA and keep their offspring alive until they themselves were old enough to procreate. If any of the many eggs or sperm that belonged to my ancestors had encountered a different egg or sperm, I would not be here, nor would anyone reading this. This is when I feel the closest to my fellow human beings. I wake up everyday thankful to be alive, able to listen to the mourning dove outside my window with my somnolent cat at the foot of the bed. And I ask, how do I convey to those who seem to hate me that my life matters as much as theirs, that we exist in this world where we elbowed ourselves into existence, that I just want to live an examined and meaningful life in this country where I was forged.

________________________________

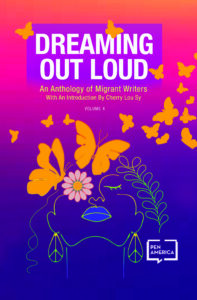

DREAMing Out Loud: Voices of Migrant Writers, Vol. 4 is available from PEN America

Luz Aguirre

Luz Aguirre is an Ame-Mexi-Pocha immigrant living in the US since 1990. She is a head-in-the-clouds renaissance woman interested in the multidisciplinary arts, philosophy, and the sciences. She was published in Voices: The Journal of New York Folklore (Fall/Winter, 2010), A-Way (Medusa Editorial, 2013), Esperanzas Desesperadas (NY Writers Coalition Press, 2013), and SOMOS: Latinx Literary Magazine (Brown University Press, Fall, 2019). She holds an AA in philosophy and a BA in art history and architecture.