Lurid, Offensive, Troublesome: On the Rise of “Underground Comix”

Brian Doherty Looks Back at the Rebellious Illustrators of the 1960s

In July 1969, a comic book got some people in trouble.

This comic book, titled Zap #4, was actually the fifth issue of the series (Long story involving sudden trips to India in search of wisdom, a newspaper called Yarrowstalks, a daring New York book editor, and a young artist who didn’t want to see his work disappear. More on that later. The sixties, man… ); it was an anthology with stories and drawings by seven different cartoonists: Robert Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Spain Rodriguez, Robert Williams, and Gilbert Shelton.

Their work in other places—album covers, rock posters, underground newspapers, hot-rodder T-shirts—was defining what it looked like and felt like to be young and strange and rebellious—or to believe you were—in the late ’60s.

The images and ideas on the comic’s cover and contained in its fifty-two pages might rub a “straight” the wrong way: A pair of decadent aristocrats sexually abusing a harnessed servant girl, with one firing a pistol ball clear through her and into the penile opening of the other, who she’s fellating (by S. Clay Wilson); an anthropomorphic clitoris tells the tale of a humanoid galaxy forcing bizarre techno-torture devices on a female-presenting being (by Robert Williams); a frustrated superhero Wart-Hog tries to fuck the reporter who loves him, but she laughs at his little curly penis, so he uses his snout to penetrate her (an uncharacteristically vulgar Gilbert Shelton).

In addition to these shocks to the system, the art pulled from elements of our visual culture that go unquestioned—a monocle and top-hatted giant peanut, trying to convince you to buy and eat peanuts??—and Moscoso’s cover turned that concept askew, portraying it in a way that helped readers see the culture shaping them with enlightened eyes, exposing the absurd and the sinister.

Zap was a capacious little pamphlet of black-and-white images sandwiched between vibrant sweet-sour color covers, giving readers room to think, ruminate, imagine their own images, think their own thoughts.

But the star of the lurid show, the most unmistakably offensive and troublesome—so far beyond what anyone might call “problematic” today—was a story titled “Joe Blow,” written and drawn by Robert Crumb.

Unlike most comics periodicals sold in America, they did not subject themselves to the authority of the Comics Code.

In linework and imagery more plastic and clunky than is typical for the generally lively and organic Crumb, the characters of “Joe Blow” seem toylike rather than human; perhaps that’s the point. We see a dad watching a blank TV musing that he “can think up better shows than the ones that are on!” who then stumbles upon his seemingly masturbating daughter. He eats “a simple pill called ‘Compo¯ z,” orders her to fellate him, and proceeds to fuck her on the living room floor until his son returns. The son runs to his mom in shock, and she asks him questions about masturbation before coming into frame in sexy lingerie.

The dad concludes, “I never realized how much fun you could have with your children,” as the kids go off together to make use of their new knowledge, and the strip shifts into mock-socialist propaganda as the parents—again looking not quite human—declare their offspring are off “to build a better world!” “Yes, youth holds the promise of the future!”

The New York Times asked Crumb about this comic in 1972. Why? How does one justify… ? Those would be some ways into the touchy topic. The Times reporter just blandly asked: “What was your intention?”

“I don’t know. I think I was just being a punk.”

Just four years prior to this, Crumb was making a living drawing funny greeting cards for American Greetings in Cleveland, but he’d transitioned into a career of blowing hippies’ minds with cartoons in counterculture tabloids such as Yarrowstalks and the East Village Other, and in 1968 broke into the mainstream with his anthology Head Comix, published by Viking.

He garnered praise from a variety of generational gatekeepers and his art graced the cover of Big Brother and the Holding Company’s Cheap Thrills, an album that topped the charts for eight weeks and starred his good pal Janis Joplin.

Crumb, now a recognized thought and culture leader by the rebellious, taboo-shaking, enlightened kids of the Now Generation, was inadvertently responsible for getting booksellers dragged to prison and forcing publishers into hiding from the authorities.

*

Zap #4 was an example, an archetypal example, of what were called “underground comix.” Unlike most comics periodicals sold in America, they did not subject themselves to the authority of the Comics Code, whose seal emblazoned the top corners of every comic book you were apt to find on a newsstand, in a drug store, or on convenience store racks all over America.

To get that seal of approval, your comic book had to be middle-American wholesome. It had to eschew “profanity, obscenity, smut, vulgarity” and “suggestive and salacious illustration or suggestive posture” and any “ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group.” None of these were things that Crumb and his colleagues could be relied on to avoid.

They didn’t just do art differently, these underground comix creators, they insisted on doing business differently and, in doing so, eventually changed the mainstream comics industry as well.

The first issue of Zap had a seal drawn to emulate the comics code that read “Approved by the ghost writers in the sky.” Ridiculing religion? Maybe. Hard to say, and as Crumb’s Mr. Natural advises on the cover, “If you don’t know by now, don’t mess with it!”

Underground comix (the “x” to mark them as distinct from the mainstream comics to which they were in opposition) were not distributed by the sort of jobbers that were also trucking Time, Better Homes and Gardens, or Family Circle around. They were instead distributed by hippie entrepreneurs, some of whom might also be slinging drugs, and generally appeared alongside drug paraphernalia (such as pipes and papers for help ingesting drugs, or posters that made you feel like you already had).

Though some were periodicals, many were one-shots either by design or by their creator’s lack of follow-through. They were not sold as ephemera to be destroyed at the end of every month with the publisher eating the expense of unsold copies like mainstream comics; rather, more like books, they would sit on shelves getting more and more dog-eared by the hands of curious thrill seekers who might not dare to actually buy them and take them home (or who couldn’t afford to) so their strange imagery and subversive ideas could successfully keep audiences and win acolytes across, if not literal generations, at least multiple waves of the rapidly shifting interests, mores, and attitudes of the morphing American youth counterculture of the late 1960s and ’70s.

Just as the wave of filmmakers who arose in that same period—including Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, and Martin Scorsese—embodied their generation’s attitudinal and experiential edges and upended the aesthetics and business model of their archetypal American art form/industry to the great pleasure of audiences, so too did the men and women who made underground comix change both comics and comedy, making everything ruder and deeper at the same time.

They were mostly a dark secret you needed to stumble across in the search for other quirky or forbidden kicks, or be initiated into by a previous acolyte, like some occult rite of passage.

They didn’t just do art differently, these underground comix creators, they insisted on doing business differently and, in doing so, eventually changed the mainstream comics industry as well. They had no interest in dealing with the existing mafias of periodical distribution or the corruption of its returns system; underground comix were thus sold non-returnable to independent retailers enmeshed in rebel youth culture without outside sponsors’ ads coming between their message and the reader.

Most importantly, the artists themselves remained the owners of their work and copyright. They were paid royalties like real authors (at least theoretically) and not merely upfront page rates as work-for-hire; and underground comix publishers printed and distributed what the artists chose to create, not vice versa.

Much of what made America juicy, zesty, strange, scrappy, devil-may-care, irresponsibly fun, and chaotically strange in the past half-century flowed through and/or out of this loosely assembled band of brothers and sisters: from hot-rod magazines to funny greeting cards, biker gangs to homemade mod clothing, psychedelic rock to science fiction, cheap girly mags to women’s liberation, smartass college humor magazines to karate, Wacky Packages trading cards to surfing, communist radicalism to born-again Christianity, transsexualism to graffiti.

They fought and lost legal battles with Walt Disney and vice squads across the nation; they labored for twenty-five bucks a page or less and reshaped their despised art form into a now essential part of the cultural repertoire of any educated hip adult.

Unlike other pop culture products—say, rock music—that similarly formed the mentality of those boomer youth out to change the way Americans thought of war, race, war, sex, gender, work, and expression, underground comix were genuinely subterranean, unsupported by major corporations or distributors or anywhere public where you might come across them unbidden, such as radio. They were mostly a dark secret you needed to stumble across in the search for other quirky or forbidden kicks, or be initiated into by a previous acolyte, like some occult rite of passage.

Despite or because of that, underground comix became an essential accoutrement of a counterculture life, despite frequently mocking, satirizing, or critiquing that life. They were seen as designed for a befuddled altered mind yet demanded and challenged (at their best) the most sophisticated levels of aesthetic contemplation.

They were absurd, scatological, goofy, innovative, scary, beatific, thrilling, heartbreaking, and sometimes shoddy, but in all their manifestations they brought pleasure, insight, and bewilderment to millions while seemingly designed to have their off-register, scrap paper, cheaply printed, stapled bodies fall to pieces in a damp rack in some grotty group house’s bathroom damp with Bronner’s residue.

Still, many of them have been carried into the consciousness of later generations via multi-hundred-dollar highly designed hardcover box sets (or on museum walls).

Underground comix were born of smartass rebel kids—some geeky, some intellectual, some impish, some violent, some disturbed, some just looking for a place to get people to read their twisted and “unprofessional” work—yearning to push back vigorously against the limits of what their culture considered acceptable or allowable. These young artists were nearly all motivated at least in part by knee-jerk censorship of the 1950s. Respected psychiatrists, Senate subcommittees, and mothers across the nation decided comic books, especially the ones smart weird kids loved the most, had gone too far.

These young artists were nearly all motivated at least in part by knee-jerk censorship of the 1950s.

Mainstream comic companies reacted with the self-imposition of the Comics Code, and the publisher these kids admired the most—EC, home of Tales from the Crypt, Shock SuspenStories, Weird Science, and Mad—shut down all the horror and science-fiction stuff and turned Mad into a magazine; shortly thereafter, the nutty genius who founded it, Harvey Kurtzman, God to this generation of cartoonists, left the publication he founded, and nothing was ever the same.

White male Jews and gentiles from the northeast suburbs, women growing up curious and arty in New York City, Hispanic young men growing up working-class rough in Buffalo and Brooklyn, a random collection of ill-adjusted kids from Texas to Kansas, together forged a misfit art and literature movement that was driven to break the law in an inky explosion of the repressed dreams of a free America.

Underground comix portrayed illegal acts—from drug consumption to forbidden sex—and were frequently illegal in their very existence. They fought a long and successful battle to change American culture against pressure from the powers that be, who condemned their art and culture as nothing but “vice” and harassed their sellers, publishers, and distributors. That pressure created an unduplicatable frisson of alternate power and fear in the men and women who wrote and drew them.

To a creator, the architects of underground comix came up in a time where the “real” art world, including those in art education (which many of them had experienced) looked down not only on cartooning but also on any art with representational or narrative content at all. With zero institutional support, the undergrounders drew against not just opposition but also condemnation—cultural, legal, and artistic. Still, they couldn’t be stopped. And they couldn’t stop themselves.

Even the most intellectual and serious among them, Art Spiegelman, who became the respectable ambassador of the history and traditions of a once sneered at American popular art turned elite, wielding unquestioned cultural power, understood where it all began for most practitioners of his art form in postwar American culture: “All cartoonists start by drawing naked girls and blown-apart bodies and monsters on lined sheets of notebook paper when they should be doing their schoolwork.”

No matter how arty or intellectual comics could be, he granted, something about that Id-creature energy was essential to the gutter form’s appeal. His colleagues in the undergrounds had that id-energy to burn, and burn it they did.

_______________________________

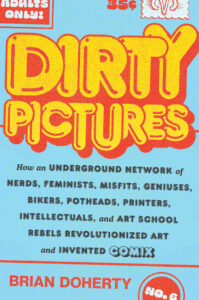

Excerpted from Dirty Pictures by Brian Doherty with permission of Abrams Books. Copyright © 2022.

Brian Doherty

Brian Doherty is a senior editor at Reason magazine and is the author of This Is Burning Man: The Rise of a New American Underground (Little, Brown, 2004). His reporting, essays, and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, Mother Jones, and Fantagraphics's The Best American Comics Criticism, among others. He has also served as a judge for the comics industry’s Eisner Awards.