Lupine Cryptids, Tornado Alleys, and Sulfuric Demons: Lillian Stone on Her Complicated Relationship With Her Ozark Roots

“I felt like a werewolf—hiding from prying eyes, not wanting anyone to see me transform.”

I was raised in the shadow of a Yakov Smirnoff billboard. It’s on State Highway 248, a half hour from my parents’ place near the Missouri-Arkansas border. Glance up and you’ll see the Ukrainian comic’s grinning face, thirty feet in the air and partially camouflaged by a Cossack fur hat. Below him lies a stick of dynamite. Danger! The billboard reads. EXPLOSIVE LAUGHTER! WITH YAKOV.

Drive a few miles down the highway and you’ll find Yakov’s two-thousand-seat Branson comedy theater. Drive a few miles in the other direction and you’ll find my hometown. Springfield is the third-largest city in Missouri, with a population that recently broke 160,000 and a shiny new Costco to prove it. It’s half the size of St. Louis, the next-largest city. You can drive from one end of town to the other in about twenty minutes if you’re really cooking, though no one ever is.

Like the Yakov billboard, Springfield is weird. In a good way, mostly. I’ve always rolled my eyes at the rhetoric surrounding other “weird” towns—places like Austin, Texas, or Portland, Oregon. Sure, your city might have a robust penny-farthing racing community, but Springfield has miles of underground limestone tunnels in which the United States government stores 1.4 billion pounds of cheese.

Brag about your hometown heroes all you want; Springfield has the Baldknobbers, a group of fearsome masked vigilantes who stalked outlaws and corrupt government officials throughout the nineteenth century. Oh, your town square’s the site of an infamous Revolutionary War skirmish? Great. Mine’s the site of the nation’s first one-on-one quick-draw duel, which took place in 1865 between Wild Bill Hickok and Davis K. Tutt.

Legend has it that the shootout began as an argument over a gambling debt, prompting Tutt to seize Wild Bill’s prized watch as collateral. Humiliated, Wild Bill challenged Tutt to a duel and killed him on the spot. After a three-day trial, a jury acquitted Wild Bill of manslaughter. They decided he had a pretty good reason for offing Tutt. A gentleman must accessorize.

The hills had lost their luster; my hometown had transformed into an entirely unknown beast.

Like I said, Springfield’s weird. I once heard someone describe the area as a “freaky vortex,” a bubbling cauldron that spits out the strangest artifacts—artifacts like Brad Pitt, who went to high school with my mother. He still comes home for the holidays, treating vigilant locals to selfies at an upscale pizza joint. When he’s not around, we settle for his brother, who is unironically named Doug Pitt.

And while the latest census data puts the median income around $38,000, it’s hard to classify Springfield as a blue-collar town. It’s got the quirk of a college town and the sprawl of a farming community; a Marxist bookstore, a firearms dealer, and a Route 66 museum are all located within a one-mile radius of the town square.

There’s an emo ice cream parlor that serves charcoal-dyed soft-serve; there’s a weekly bluegrass hour on the local NPR station. Close your eyes and throw a Yakov flyer and you might hit a grizzled moonshiner, but you’re just as likely to hit the frontman of a moderately successful indie rock band. Accents run the gamut from deep, twangy hill chatter to vocally fried barista-speak.

We’ve got open-carrying millionaires who made their fortunes in the trailer hitch industry; we’ve got crunchy California transplants eager to shake up the composting scene. For every berry farm, there’s a semirural gated McMansion complex; for every McMansion, there’s a cozy midcentury bungalow flanked by Little Free Libraries. It’s a place full of contradictions. A place full of lore.

It makes sense that urban legends would flourish in a contradictory town like Springfield. The topography alone is pretty spooky. The Ozark Mountains ooze hillbilly folklore, with swirling mists that produce claims of howling beasts and vigilantes in black horned hoods. Down below, untouched caves lie beneath ancient layers of dolomite. In between, urban legends are born of conflicting accounts.

There’s the abandoned plot of land near my childhood home that supposedly once housed Camp Winoka, an apocryphal summer camp where a dozen Girl Scouts were brutally slaughtered. Some say there never was a camp there; others say it was Cubs, not Girl Scouts. Once, my sister went to see for herself. She swears she saw members of a devil-worshipping cult through the trees. Her friends say it was a sorority.

Then there’s the Albino Farm, an overgrown nineteenth-century settlement on Springfield’s far north side. It’s allegedly haunted by the ghost of a spiteful groundskeeper with albinism. Or did the groundskeeper’s wife have albinism? Or did the groundskeeper simply breed albino catfish? And are we even still using albino as a descriptor? Or groundskeeper?

My favorite legend involves a beast that can’t make up its mind. Growing up, I kept my eyes peeled for the Ozark Howler, also known as the Hoo-Hoo, the Nightshade Bear, or the Devil Cat. The Howler is said to stalk the Ozark Mountains’ dark, craggy ridges, guarding the no-man’s-land near the Missouri-Arkansas border. The beast is bear-sized with stocky legs, black shaggy hair, glowing red eyes, and thick, horrible horns. Even worse is the Howler’s telltale cry, described as something between a wolf’s howl, an elk’s bugle, and the laugh of a hyena.

I learned about the Howler in a library book. I was nine or ten, and I had already plowed through my elementary school’s kiddie horror section, stealing away with five Bunnicula paperbacks at a time.

I was hard on library books, baptizing Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark anthologies in the bathtub until I emerged, shriveled and shivering, to read under the covers. I broke spines and dog-eared pages with abandon until the Dewey Decimaled horror section seemed to beg for respite.

At that point, I moved on to the local history shelf. I pawed through pamphlets for nearby Civil War battlefields and impatiently sampled an 1880 homesteader’s diary. Finally, I landed on a well-worn collection of Ozarks myths and legends. I lowered myself to the ground, sitting cross-legged on the thick carpet as I took in tales of a beast that’s part cat, part bear, and part wolf.

No one can agree on the Howler’s exact physical characteristics. The only thing we can agree on is that it’ll just as soon eat you as look at you. That’s what makes it so scary—by the time you realize what you’re looking at, it’s too late. The Howler contains menacing multitudes, capable of shifting into everyone’s worst nightmare.

One minute, it’s a dusty old dog curled up by the fire; the next, it’s eating your granny. It’s lupine to some and ursine to others. It is unwieldy, dodging capture and definition, beholden to no one and mastered only by otherworldly possibility. It’s the perfect cryptid for a town like Springfield, which can’t seem to make up its mind about what kind of town it wants to be. And it’s the perfect cryptid for me, a breathlessly nostalgic Ozarks expat who can’t make up my mind about my relationship with my hometown.

I didn’t leave Missouri until I was twenty-four, later than most. My hometown is one of those places where you either scuttle away at eighteen or stay for life, sucked in by affordable real estate and, if you’re lucky, a wild sexual affair with a smoothie artist at the local health food store.

I stuck around for a cheap college education, got a few jobs under my belt, and then headed north to Chicago to live out my big-city fantasy. The fantasy had been brewing since I first visited Chicago at twenty and wept in awe upon seeing a two-story Walgreens, with escalator. Other than the giant Walgreens, I didn’t have a great reason for choosing Chicago, though I now know it to be the greatest city in the world. There are lots of cities, and probably lots of multistory Walgreens pharmacies. In the end, Chicago was the biggest city within U-Hauling distance at a time when I felt restlessly, frantically itchy.

I’ve always been itchy, though not in the way you’d expect from syrupy Hallmark depictions of small-town girls longing to break free. I was—still am—a homebody. I didn’t feel oppressed by my surroundings; I felt oppressed by my own uncertainty.

I spent my teen years scratching at that sense of oppressive possibility; the knowledge that the world could, someday, be mine for the taking, if I only had the courage to leave my parents’ driveway. I mean that literally: I used to spend warm nights leaning against the garage door, staring upward in the most dramatic possible interpretation of teen angst and feeling like I was about to bust out of my skin amid the vastness of rural suburbia.

The angst lay entirely in my own terror of growing up, of shapeshifting into something that my hometown might find as horrific as the Howler. I wanted to become something large and loud, something fanged and famous, the kind of person who lives in a sleek high-rise and smokes from a long-handled jade cigarette holder and leaves her hometown without looking back.

At the same time, I wanted to curl up under my great-grandmother’s scratchy crocheted afghan and renovate the farmhouse a mile from my parents’ place, becoming the kind of person who smells of bonfires and develops a deeper, richer twang with age. I felt those menacing multitudes brewing deep in my pseudo-hillbilly heart, and I was terrified. I didn’t want to let anyone down. In the end, the only way to treat the itch was to make a move, to slink away from the prying eyes of the Ozarks and figure out what I wanted on my own terms.

My family made it hard to move away. Most of them live within a ten-mile radius, and I struggle with an advanced case of paranoid FOMO, prone to teary-eyed brattiness when anyone has fun without me.

My family is also full of poor communicators. My siblings and I do okay, mostly swapping hideous selfies and diarrheal anecdotes. My parents are worse. My dad and I communicate almost exclusively via screenshots of old Far Side strips. Not long ago, my mom mailed me a greeting card:

Thinking of you. I hope we get to live near each other again before I die.

FOMO and sporadic texting aside, my family is rich with superstition and exaggeration. They’re not the kind of people you want to offend by moving far away. My mother’s people trickled out of hills and hollers, starting pig farms and doing hair and getting married and divorced enough times to produce me, a confused girl child with strong legs and a weak constitution.

We’ve never been good record-keepers, with elders too dazed from cigarette smoke to pass along accurate anecdotes. My mother tells me how her father ran wild with his brother Randy, seducing unsuspecting women with dirty music and devilish good looks. My aunt tells me my grandmother once saved a kid’s life by diving ten feet into the deep end of a public pool with her shoes on. My great-uncle tells me that somebody, at some point, shot and ate a squirrel.

My father’s side of the family is less exciting, though it doesn’t stop him from self-mythologizing. He’s a transplant from Texas who employs his lingering Amarillo accent to insist that Houston is not, in fact, real Texas. He brags about eating canned rattlesnake. He insists that he once saw Stevie Nicks naked. He’s the only person I know who lacks a healthy fear of funnel clouds, which is a problem because my hometown is situated in the heart of Tornado Alley.

Once, he piled my siblings and me into the backseat during a tornado warning, bone-chilling sirens and all, to do a little grocery shopping. After our cart was full, the store manager came over the loudspeaker to announce that a mean twister had touched down nearby.

My dad took this as a challenge, calmly placed us back in the truck with the groceries, and zipped home down the highway, racing the black cloud as it got bigger and bigger behind us. This is how I die, I thought. In a car with my stupid, round-headed kid brother.

So, yes, things get blown out of proportion in my family. I’m the child of a father who laughs in the face of funnel clouds and a mother who knows how to use lit cigarettes to extract ticks from her flesh. With those roots, it’s no wonder I lapped up local mythology and leaned into the golden rule of mythmaking: that the scariest bits exist in the empty spaces.

The glint in a werewolf’s yellow eye; the smell of sulfur before a demon descends on an unsuspecting village; the sound of a hook screeching against the hood of a parked car. As I prepared to leave Missouri, I knew it was time to fill my own empty spaces, potentially creating something beastly in the process. I felt like a werewolf—hiding from prying eyes, not wanting anyone to see me transform.

I became ardently defensive of the Ozarks, rearing back with a roar every time someone dared perpetuate tired hillbilly stereotypes.

I was kidding myself; the transformation had already begun. I spent my early twenties growing resentful of my surroundings. I had seen one too many bruise-colored tornado skies and endured one too many catcalls from cruel young men in pickup trucks. I had undergone a full-scale sociopolitical awakening that didn’t square with my parents’ allegiance to Mark Levin.

I had become hypersensitive to the ugly parts of home, rolling my eyes at the rotting hay bales spray-painted with alt-right messaging and avoiding my favorite coffee shops, which suddenly seemed to be crawling with sneaky Evangelicals disguised beneath cool beanies. One minute, they’re serving you an expertly crafted cortado or advising you on Mailchimp strategy; the next, they’re sadly shaking their heads at your sexuality. They wear hipness as a skin, lacing up their lightly worn Doc Martens and strutting into Sunday morning service to remind themselves of their own noxious superiority. They’re the Roger Chillingworths of the Soylent age.

As I considered the beastly aspects of home, I began to feel scrutinized in a way I couldn’t stand. In a town like mine, anonymity is sacrificed in favor of cheap gas. Everyone knows everyone’s business, and my business had grown progressively messier as I entered adulthood. I could walk through the town square and see my old Sunday school teacher, a man who’d once drunkenly tried to run me over on his longboard, and five people who all knew the intimate details of my latest breakup.

It made me feel like I was thirteen again, sitting in my parents’ driveway and wriggling around in too-tight skin. It made me bitter. It made me crass and lazy, joining outsiders in treating the Ozarks as a punch line. I rolled my eyes at the folklore I used to love and laughed along with yee-yee memes about the merits of the humble corncob as a toileting implement. The hills had lost their luster; my hometown had transformed into an entirely unknown beast. I had, too.

So I moved. I rented an apartment and settled into Chicago’s far north side, all feminist bookstores and vintage markets and coffee shops that almost never set off my Evangelical radar. I relished the anonymity, astonished that I could strut braless down the sidewalk without garnering the disapproval of a former employer. I could live there for years, I reasoned, and never run into anyone from junior high.

I was shocked the first time I got catcalled by a man in a pickup truck. I was walking down my Chicago neighborhood’s charming main street, window-shopping and swinging my winsome tote bag. I heard him—“NICE ASS!”—before I saw him. I whirled around and stared at him in disbelief. “YOU CAN’T DO THAT HERE!” I yelled after him, shaking my fist. “DON’T YOU KNOW THIS IS A BLUE STATE???!!!”

Not long after, I started noticing cracks in my glamorously imagined big-city facade. The catcalls continued. Local political leaders outed themselves as bigots. One of my neighbors debuted a bumper sticker that read I’M PROUD TO BE AN AMERICAN. IF YOU’RE NOT—PISS OFF! Naive and self-satisfied, I thought I had left such sentiments behind in the land of Yakov Smirnoff billboards. Turns out, that stuff lives everywhere. Some places are just better at hiding it.

I started missing home about a month into my lease. My hometown bitterness had emboldened me, bolstering my courage and sending me north. The scorn faded almost immediately after I moved. I became ardently defensive of the Ozarks, rearing back with a roar every time someone dared perpetuate tired hillbilly stereotypes.

I rolled my eyes at the coworker who asked if I’d ever eaten a possum. (No—they’re very hard to catch.) I snarled at peers who suggested that Ozarks politicians are an effective measure of locals’ values, as if the region hasn’t been held hostage by high-powered bigots for generations.

Once, on a trip home, I snapped at a gaggle of travelers waiting in line at the Springfield-Branson National Airport coffee shop. They were debating their plan of action during a long layover. “We might as well stay put,” sniffed one woman in a pair of bejeweled riding boots. “It’s not as though there’s anything around here other than cow patties.” I shot her a look liable to kill Wild Bill Hickok himself.

__________________________________

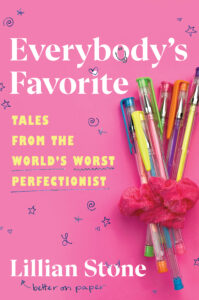

From Everybody’s Favorite: Tales from the World’s Worst Perfectionist by Lillian Stone. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of William Morrow, a division of HarperCollins Publishers.

Lillian Stone

Lillian Stone is a humor writer, journalist, and regular contributor to The New Yorker, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Slate, and others. A leader in the online humor and satire space, she was named one of Paste magazine’s 15 Best Humorists Writing Today. She lives in Chicago.