Modern Tourism Makes It Difficult to Truly Appreciate the Sistine Chapel

Jeannie Marshall on Why We Need to Slow Down and Sit in Silence to Take in Works of Art

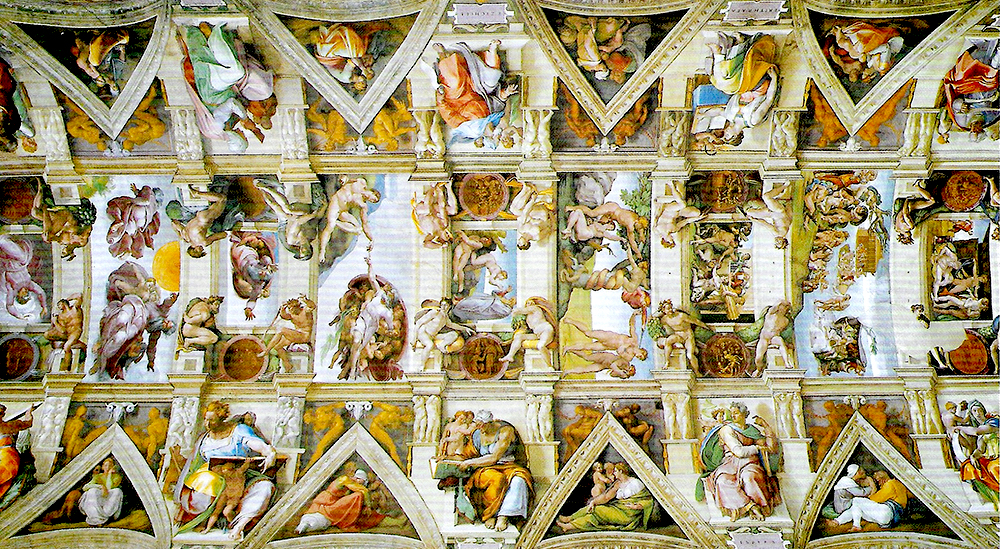

The Sistine Chapel frescoes are much looked upon but rarely seen. And this is not exactly because of a collective failure in those who travel from all over the world to see them. Okay, maybe you could have read a little more about the images themselves, to understand the significance of the expulsion from the garden of Eden and the depiction of Noah and the story of the flood.

But you’ve come for more than just the facts, which you could acquire without leaving home. I would bet that you’ve come to see great art because you want to know what it feels like.

Inside the Sistine Chapel I once experienced a sense of myself in time, as a body of energy that has existed forever with a consciousness frustratingly limited to now. But I also felt my consciousness reaching through the images painted on the ceiling to connect to the mind of an artist who has been gone for nearly half a millennium and who himself was trying to connect to the thoughts and stories of the past, maybe even to God. It was quite something.

And because of that experience, I have returned numerous times, and I have approached that feeling again while looking at the images of the pagan sibyls and at the frescoes as a whole, though never quite with the quiet shock of the first time when it crept up on me while I sat on a bench under the scene of the flood.

And isn’t that why we go to visit famous works of art, why we travel and build our holiday plans around a trip to see Leonardo’s Last Supper in Milan, Botticelli’s Primavera in Florence, and Michelangelo’s frescoes in Rome? Or are we just checking things off a list: Raphael’s School of Athens—done. Michelangelo’s Last Judgment—done?

You might wish you had learned more about Michelangelo while you are standing elbow-to-elbow with a room packed full of your fellow travelers trying to get a look at the ceiling, trying to find one image to hold onto. Maybe it’s the famous one of God and Adam reaching toward each other, or maybe it’s the Prophet Jonah with a fish tucked under his arm.

And just as you’re thinking—hey, didn’t Jonah get swallowed by a whale? And what is that look in his eye?—one of the guards will demand silence through a thought-shattering loudspeaker while another guard tries to herd you toward the exit.

The reason I was able to catch a glimpse of the strangeness inherent in these images and to feel anything at all, was because I managed to get a seat where I could rest away from the current of bodies that were moving me toward the door and out of the room that I had spent all morning trying to get into.

When I sat down, I could disconnect from the chaos around me and connect with the surprising sight of the victims of the flood depicted in the moments before all was lost, when maybe there was still a chance left in their minds that they might make it. And then to remember that, of course, they do not.

When I sat down, I could disconnect from the chaos around me and connect with the surprising sight of the victims of the flood.Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel frescoes are so hard to see. They unravel a view of spirituality, a poetic and nonlinear embrace of human origins that the Catholic Church veered away from after the Renaissance. To really make it difficult, the ceiling is about sixty-five feet overhead.

Even if you could lie down on the floor (you can’t, don’t even think of it), it wouldn’t help. And if you try to use binoculars, you will be able to see some detail but lose your sense of the whole (and feel queasy afterwards and have to miss lunch).

Another problem is each other. There are too many of us there on holiday, all at once, all of us wanting to see the same thing. We might have the best of intentions. We might truly want to see this feverish, sensuous, dream of sixteenth-century spirituality and we might also want to understand how it spirals out of the Vatican Museums and into the streets of Rome. We might want to find the historical connections in the contemporary city that run through the Renaissance and back to the pre-Christian ancient world of the Caesars.

But the problem with art tourism, as with tourism in general, is simply each other. There we are, each on our own mini grand tour, but we cannot get away from the rest of us. We’re like Lucy and Charlotte in A Room with a View unable to shake off Mr. Emerson and his son, except multiplied. There they are again, doing everything that we’re doing.

Only now we can hardly walk through the historic centre of the city on a summer night because there are so many of us, consulting our apps and looking for that authentic trattoria, which, when we find it, is lined up with people just like us, clutching our phones, consulting our apps. We can’t quite grasp that elusive sense of meaning in the artwork when being squashed into churches and galleries with our fellow travelers.

The director of a museum in northern Italy once told me that cultural institutions shouldn’t use numbers to measure their success. They shouldn’t count turnstile clicks and revenues. The point of such places is not to make money but to allow visitors to experience the art, to allow it inside themselves, rather than to graze the surface as they walk past paintings, clicking their phone cameras presumably to look at the images later.

But how does an institution measure your experience of the art? Should they ask you some questions as you’re leaving? Excuse me, but did you have any meaningful experiences today? Has the sense of your place in the universe been altered? Would you say quite altered, only a little altered, not altered at all?

The difficulty of modern tourism when it comes to seeing art is that we need a little quiet.Will you walk out of this place, buffeted and bumped in this stream of humanity and feel a little flutter in your stomach for having caught the edge of a thought that came from a world that no longer exists? And if only you could just be left alone with it and your own mind, do you think you might be able to take hold of it?

The difficulty of modern tourism when it comes to seeing art is that we need a little quiet. This isn’t because we art lovers are so precious, but because it takes time and humility to look down the centuries to see that these artists who were wrestling with their own questions about existence and how to live a good life in the eyes of their god were working on a puzzle that has never been solved.

And you feel that if you could be allowed a few tranquil minutes, you might be able to sense something close to meaning in your own life, something that includes you and these long dead artists, as well as the generations of people yet to come, and, even though you might not want to admit it in the moment, includes the guy next to you who is loudly filling the air with information.

Art tells us something we need to know, but it does so quietly. So, next time you find yourself in the presence of a piece of art that has been gazed upon so much it’s in danger of disappearing behind a curtain of familiarity, try to remember to close your mouth and open your eyes. See if anything happens.