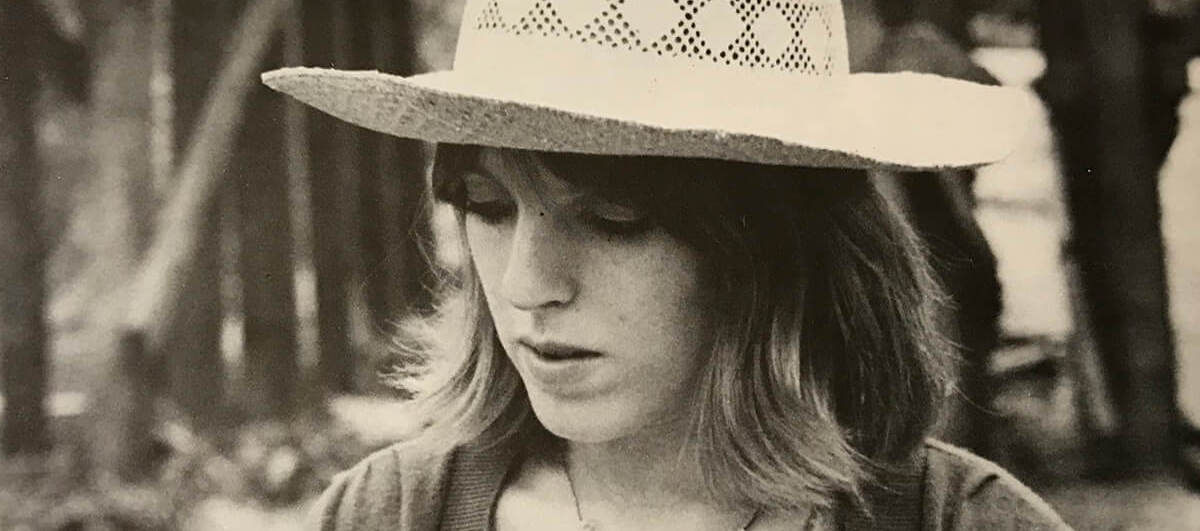

Lucinda Williams Recalls the Turbulence of Growing Up With a Sick Mother

“Your mother’s not well, don’t be mad at your mother.”

In the summer my father would drink gin and tonics. When I was a kid, he would say, “Honey, can you go make me a drink?” I knew how to pour gin into a shot glass and into the cocktail glass with ice and then pour in the tonic, add a piece of lime. Nobody back then thought there was anything bad about that.

I remember reading an article about Eudora Welty describing how she would have one small glass of whiskey in the late afternoons before dinner. It was her little treat, a way of relaxing at the end of the day, having a cocktail. In the same manner, my dad and my stepmother, Jordan, who I called Momma Jordan or Momma J, would partake of a glass of wine or a cocktail at the end of the day, and my dad would open the day’s mail and we’d talk about current events or anything else.

We’d sit in the sunroom off the living room. It was all glass and it felt like you were sitting outside. You could enjoy that room all year round because you didn’t have to worry about bugs but you could enjoy the natural light. In the winter it would be delightful because there was a potbelly heater out there to warm the room.

I had different experiences with my mother and her drinking. She was not a social drinker. She drank in private, a closet drinker. I didn’t realize this until I was around age eighteen when I was visiting my mother at her apartment in New Orleans and she came to the door slurring her words. For years she had always said it was her medications. I was used to seeing her like that. She had spent a lot of time in mental health hospitals and various therapy clinics and she was on medications. But it suddenly occurred to me on this visit with her in New Orleans that on top of that she was drinking heavily. I didn’t know she was an alcoholic until then.

Her maternal instincts or maternal abilities were taken from her by her mental illness. We were close until she passed away in 2004, but after a certain point I didn’t depend on her for anything. I learned at a very early age that I wouldn’t be getting from my mother what most kids get from their mothers, the stability and warmth and reliability and support. I never felt any pressure from her, either. I mean, she didn’t

have that capacity.

Looking back on it, many of my traits that might be considered good traits came from her. She read everything. She played piano and she listened to good music. She loved Judy Garland and Erroll Garner and Ray Charles. She also introduced me to Joan Baez and Leonard Cohen.

As I grew older and more aware of her mental illness, I began to compare her situation to that of Sylvia Plath and in many ways to Anne Sexton. Both Plath and Sexton committed suicide. My mother didn’t commit suicide, but she did check out in other ways, at least from the point of view of her children.

My mother was obsessed with psychotherapy and read every book about it that she could get her hands on. She was in therapy all the time and in and out of psychiatric hospitals. She had electroshock treatment back when they didn’t have the drugs for depression that we have now. She was on lithium and she hated it. Lithium had horrible side effects, like nausea and diarrhea and skin problems and weight gain and fatigue. Because of that she’d stop taking the pills. Then she would act out in a very hostile manner and my father would say, “Oh, she’s not taking her medication.” That’s a lot for a kid to deal with.

It was back and forth; she couldn’t live with a piano or without a piano.

Early in my life everything involving my mother revolved around hospitals and therapists and drugs. I was always hearing comments from my father like “Your mother’s not well, it’s not her fault, your mother’s not well, don’t be mad at your mother.” I understood that. It was actually a sort of generous thing for him to say about her. But I was left without very much to grasp on to. I would think, “Okay, my mother isn’t here for me.” I understood that. It wasn’t easy. I had to pick my spots and pick my times when it was okay to engage her.

My mother’s name was Lucille Fern Day and she was born on December 31, 1930. Her parents were the Reverend Ernest Wyman Day and Alva Bernice Coon Day. She went by Lucy. Her father was a Methodist minister, so conservative you’d think he might have been Baptist. He was a hellfire-and-brimstone type of evangelical preacher. The Methodist Church moved him from town to town in Louisiana every two or three years. Both of my grandfathers were Methodist ministers, but my mother’s family was much more closed-minded. She had four brothers, three older and one younger.

Her younger brother, Robert, died on his motorcycle coming home from World War II. That was before I was born. I always heard from my mother that he was the sensitive one in the family. He was a poet and, along with my mother, a musician. My little brother, Robert, was named after him.

Mom studied music but didn’t pursue a career in it. My understanding is that she started playing piano at the age of four. She fell in love with it. But music became her albatross, the piano was her albatross, because she wasn’t allowed or able to pursue it as a career. It became a symbol for what she could not do. Nobody in her family encouraged her to take it seriously. I’m not going to say that her inability to pursue a career in music caused her mental illness, or influenced it, because I think most of it was biochemical. But she struggled so much with not having a career in music. It affected her confidence or lack thereof.

We had a piano in the house when I was growing up. After my parents divorced, Mama still had a piano with her wherever she lived. But the piano would come and go. It was a joy and a burden at the same time, a love-hate relationship. She would long for a piano and then get rid of it after a while.

She never explained why and I didn’t ask. When those feelings overwhelmed her, she would get rid of the piano. Then a short time later she’d go out and get another one. It was back and forth; she couldn’t live with a piano or without a piano. She wasn’t like Bette Davis in one of those old movies, running around with smeared lipstick. Her mental illness was more understated and subtle and at the same time monumental.

My mother told me that when she was a kid, her family didn’t have plumbing and they used newspapers for wallpaper and insulation. They were all working-class and didn’t care about school or going to college. I don’t know how one sibling can be born into the same family as other siblings, and grow up the same way, and come out so different. She had an intellectual mind, read good books. It was a testament to her capabilities that she broke out and went to college and became a well-read person because none of her relatives were like that at all.

My mother met my father when she was studying music at LSU. My mother’s family hated my father. He was the literary poet guy. Although they were both church families, his family was liberal and open-minded. My mother wanted to be in a more progressive world and my father offered a way into it.

Later in my life my father told me certain things about my mother being sexually molested in horrifying ways by her father and one or more of her older brothers, repeatedly, when she was a youth. This was confirmed to me later by my sister, Karyn, who attended therapy sessions with my mother when she was older. Karyn didn’t tell me this for years and years and I don’t think she made the wrong decision to withhold it. Learning about this was unthinkably horrifying and upsetting, and I’m still trying to process it.

I have memories of my mother being happy, and of us being happy together. She had a great sense of humor. We would laugh at all sorts of things. But she would drift in and out of her illness like Sylvia Plath did. My father told me that she was once diagnosed as having manic depression with paranoid schizophrenic tendencies. Back then they didn’t have the medication we have now.

Mom talked about her psychiatric care and would quote passages from her psychology books and jot notes in the margins. She read Jung and she read that popular book from the 1960s I’m OK—You’re OK. She was very aware of her mental illness. After I moved away, we would talk on the phone for hours about psychology and the latest therapies. I learned so much from her.

She was sent into mental hospitals from time to time after she had nervous breakdowns. My father used to say that everything with her seemed fine when they were dating and before they got married. Then they got married and they didn’t have much money. My father was a struggling itinerant professor moving around and working at various colleges. This was in the early 1950s and my mother wasn’t working, because most women did all their work at home.

Kids will end up blaming themselves. All of that energy goes somewhere.

I was born on January 26, 1953, in Lake Charles, Louisiana. You could say that I was a born fighter. Like most people I don’t have a clear memory of my earliest years, but my father always told me that right from the beginning I had to fight. I was born with spina bifida, which is obviously not the best malady for someone who would go on to spend a couple of hours every night standing on a stage, but I’ve managed to overcome that just fine. As a young child I was often sick. When I was about one year old, my windpipe became blocked and I had an emergency tracheotomy. My father said it was touch and go, but I made it. I still have a visible scar from that procedure, and every time I look in a mirror, it’s a reminder of my difficult beginning and that it’s possible to grow stronger.

My struggles continued for another couple of years. At one point I developed croup and had to be put in the hospital in one of those oxygen humidity tents, and then I was quarantined at home in another oxygen tent in my bedroom.

Things grew more difficult between my parents after I was born, and my father always said I got the worst of it. I was their first baby and the responsibilities caused all sorts of new stresses and new tensions. When I was very young, my mother would get in these hostile moods and nobody ever knew what caused it or triggered it. My brother, Robert, was born two years later and my sister, Karyn, two years after him.

For years, as both a teenager and an adult, whenever I was having my own problems, my dad would say to me, “Well, honey, once when you were three years old, before your brother and sister were born, I came home from work and your mother had locked you in a closet because you were being a typical three-year-old and crying and she couldn’t handle it.” That was his explanation for my troubles. He was intellectually minded and was really into Freud. So he was always analyzing things, and he would tell me that story as an explanation of how things were for me as a child. Mom wasn’t being mean, he’d say. She just couldn’t deal with it. She probably thought I was safer locked in the closet.

When I think about it now, it sounds so horrible. How could a mother do that? But there was always my dad there to say, “She can’t help it. It’s not her fault. She’s not well.” My mother used to tell me stories about how poor we were when I was a baby and toddler. She said she had to borrow bread from the neighbors to feed us. Also, they didn’t have a crib for me, so she pulled a drawer from a chest and turned that into my bed. Poverty put even more stress on my parents’ already fragile relationship.

If a child drops something on the floor, a healthy family would say, “Oh, that’s okay, honey, we’ll clean it up.” My mother would say, “Goddamn it!” Everybody was walking on eggshells around her. My dad wasn’t Mr. Perfect, either. He would get irritable and I never knew what kind of mood he was going to be in. Sometimes he would say things to me like “If you keep doing that, I’m going to knock your teeth down your throat.”

But I bonded with my father in a way that I might not have if my mother had been more stable, if she’d been more available to me emotionally. When my mother would be really bad off—yelling, screaming, cussing, throwing things at my dad or at the wall—he would take us out to play Putt-Putt or to see a drive-in movie, anything to get us out of the house. He took on the role of what a mother would do back in those times.

Despite this, I didn’t grow up hating her, or feeling any kind of resentment, because of my dad always saying, “It’s not her fault. She’s not well.”

Recently my sister, Karyn, and I were looking at some old family pictures and out of the blue she brought up a memory of us playing Putt-Putt. I could not believe it. She’s four years younger than me, but she had the exact same memories of playing Putt-Putt with my father. That was a very powerful moment for me.

I’m 70 years old and I’m still working through a lot of this. I’ve held back from talking about my childhood over the decades of my life—I’ve written songs about it instead—because I think I came to think of it as normal. “Okay, my mother is freaking out and yelling; my dad is in a bad mood today.” I could tell that everybody was trying. And that seemed normal, the trying.

I still remember one of my favorite photographs of my father and me. I’m about two years old. We’re standing on the front steps of our house, and it looks like we were getting ready to go to church, or we had just come back from church, because he’s got his suit on, and I have a little dress and a little jacket on. It just has such a sweetness and innocence to it. The two of us are just on the front steps together. You can see we had this special bond. I had been so sick, and by the time I was born, my mother’s mental illness had started to rear its ugly head, so my father was taking care of me more and more.

Now that I’ve read a lot of psychology books and been through extensive therapy and self-education on mental illness and dysfunctional families, I realize that I didn’t have any way to recognize or deal with this trauma that happened to me. Kids will end up blaming themselves. All of that energy goes somewhere. You’re the little kid sitting in the locked closet, thinking and feeling, “What did I do that was wrong?” But then my dad was saying, “It’s not her fault, she’s not well, you can’t be angry at your mother.” What was I going to do with all that sadness and confusion and anger?

Not long after we moved to Baton Rouge, when I was eight years old, I was sent to see a child therapist. I vaguely remember just sitting in a room with this woman, playing some kind of board game. My dad told me something like “Well, we were concerned that maybe you were, you know . . . because of your mother’s illness.”

I don’t think I was acting out or anything. It was just a matter of precaution. “We need to make sure everything’s good,” he said. Maybe my mother was going through a particularly bad time and he feared I was being traumatized by it.

A couple of years ago, I was in a bar in New York and an older gentleman came up to me and asked me what I was working on. I said this book. He’d had something to do with the music business. He told me, “Don’t write about your childhood. Nobody wants to read about that. Just write

about your music. Just pick a part of your career to write about.”

But my childhood informs so many of my songs. Some listeners hear these memories and feelings in my songs. One woman came up to me after a show at the Dakota in Minneapolis and asked, “Did you have a rough childhood?”

I nodded my head as I was making my way backstage.

“I thought so,” she said.

__________________________________

From the book DON’T TELL ANYBODY THE SECRETS I TOLD YOU by Lucinda Williams. Copyright © 2023 by Lucinda Williams. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Audio excerpted courtesy of Penguin Random House Audio from DON’T TELL ANYBODY THE SECRETS I TOLD YOU by Lucinda Williams; Read by Lucinda Williams.

Lucinda Williams

Lucinda Williams is an iconic rock, folk, and country music singer, songwriter, and musician. A seventeen-time Grammy Award nominee and three-time winner, she has also been nominated twelve times for Americana Award, which she has won twice. Williams was named “America’s best songwriter” by Time and one of the “100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time” by Rolling Stone.