Lucille Clifton Didn't Just Write Poems. She Inhabited Them.

Tracie Morris Remembers a Reading at Cave Canem

I’m riding shotgun in a big Cadillac. My friend who’s driving, a buddy for years, is comfortably past six feet tall. We’re heading from the Uptown to Jersey. Someone he wants me to meet, he says. My seat is much closer to the glove compartment than his is to the dashboard. I’m eagerly looking out while he’s more laid back.

Time flies on the turnpike as we chit-chat about friends, art and how fun the hang is in this slick old-school mobile. We roll up, me for the first time, at the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival. After parking this huge car somewhere, Harlem native son Sekou Sundiata strides out like they learned to do from birth where he’s born.

We don’t even go inside a venue. (I don’t know my way around but I learned in the late 1980s, before I really started writing, that Sekou was a poet to follow.) Here in dodge, circa the mid-’90s, we sidle up to the author’s table, where my multi-hyphenate mentor introduces me to the luminous poet, Lucille Clifton.

One thing I learned from my inevitably inadequate introduction of Ms. Clifton that day was how to own a poem one is reading.

I didn’t know her or her work, podunk that I was. I did have enough sense to know that if Sekou drove out because he looks up to her, I should get the 411. That day after her gracious welcome outside sitting at a fold up white table, I bought Good Woman.

Fast-forward a few years later and I’m at one of the early years of the Cave Canem summer program in the late 1990s. By then, I knew who Lucille Clifton was, and I’d memorized one of her poems. At the Cave Canem event, I was honored to introduce Ms. Clifton for her reading in a monastery in upstate New York, a fitting environment for her. Other great Black women of poetry of letters, including Cave Canem’s celebrated co-founder Toi Derricotte and the legendary Sonia Sanchez, were at Cave Canem then, just an indication of the company in attendance along with newbies and rising stars in the African-American poetry world.

One thing I learned from my inevitably inadequate introduction of Ms. Clifton that day was how to own a poem one is reading. Up to that point I’d always memorized and recited one of her poems I love, like a private prayer. She, however, read it like a declaration of power. The confidence, the grace, the clarity, the strength of vulnerability was in her voice, her bearing. To be able to read well is one thing; to be able to read aloud as excellently as one writes their own great work is rarer.

Lucille Clifton’s work sings and tells the clear truth on the page. Her poems are grounded, are the ground. They are words of power. Hey, these are objective facts. Something that her first editor, the first person to bring Ms. Clifton to the attention of the publishing world, Toni Morrison, obviously knew. Along with Angela Davis, Toni Cade Bambara and many others, the person who was to become Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison, was a revolutionary editor at Random House who knew how to select great Black women writers and to support them early in their illustrious publishing careers.

What is it about Lucille Clifton? Not enough people know who she is, the importance of her writing. She writes about you, it feels that personal. She is, a poet’s poet. The type of poet that most anyone would know is great. All kinds of people should know about Ms. Clifton’s writing the way Black poets have to know. How could we not? The way our dearly departed Toni Morrison and Sekou Sundiata knew. Reading Lucille Clifton is like hearing from a dear, down-home, elegant friend, with time to tell you what you need to know.

Lucille Clifton’s work is unflinching and there is also joy in it. The joy of it, of reading it, will put one in better stead.

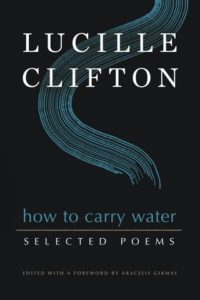

How do you get to know Lucille Clifton’s work if Sekou didn’t drive you to her? The formidable poet and professor Kevin Young co-edited the first collection of Clifton’s work (with a foreword by Ms. Morrison herself). That book, The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton 1965-2010, received heaps of well-deserved praise when it was published in 2012. And now, a new, important book of Clifton’s selected work, How to Carry Water (BOA Editions, 2020) is edited and forwarded by the excellent Araceils Girmay, and really should be in your library.

Girmay’s tender foreword has the almost prayerful meditation that Lucille Clifton’s work and presence cultivates in people. The new wonderful book also has a plethora of uncollected poems (and even drafts) by Clifton that are essential reading for anyone who loves or wants to love poetry. At the end of the book, Girmay is sure to remember the many of us who were not (nor could ever be) peers of Lucille Clifton but who were deeply affected by her work, life and discipline.

At the beginning is Girmay introducing Clifton, then there’s Lucille Clifton then there’s us thinking about her, the legacy of this work. Lucille Clifton’s work is unflinching and there is also joy in it. The joy of it, of reading it, will put one in better stead. How to Carry Water steels the reader for the road ahead. Reading this selected poetry is riding with a friend, while shooting the breeze, unbeknownst to you, you’re about to encounter the extraordinary.

__________________________________

Lucille Clifton’s How to Carry Water: Selected Poems is available from BOA Editions.

Tracie Morris

Tracie Morris is writer/editor of 7 books and is a poet, professor, performer, voice teacher and theorist. She holds an MFA in poetry from CUNY Hunter College, a PhD in Performance Studies from New York University, and studied British Acting technique at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London. Her most recent poetry collection is Hard Kore/Per-form: Poems of Mythos and Place, Joca Seria, 2017 (English with French translation). Tracie became an Atlantic Center for the Arts Master Artist in 2018; that year she also served as the 2018-2019 Woodberry Poetry Room Creative Fellow at Harvard University. Tracie was the inaugural Distinguished Visiting Professor of Poetry at The Iowa Writers Workshop for three semesters before joining the permanent faculty as their first African-American Professor of Poetry in Fall, 2020.