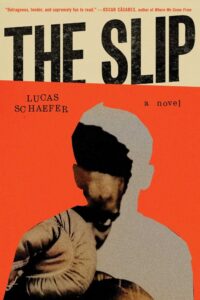

Lucas Schaefer on Troubleshooting a Problem Character

“A lackluster character was on the prowl, and he’d become the King Midas of meh.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

My former writing professor Elizabeth McCracken used to warn us about the dangers of letting a character’s bad habits become a story’s bad habits. The glib protagonist sauntering through a narrative that never transcends his flippant observations; an emotional vampire who sucks the energy not only out of her friends but also the reader. A couple years into drafting my debut novel, The Slip, I realized I’d failed to heed McCracken’s counsel. A lackluster character was on the prowl, and he’d become the King Midas of meh, turning everything he touched humdrum and colorless. Including, alas, my book.

The Slip concerns sixteen-year-old Nathaniel Rothstein, a dumpy sad sack who, after getting into a fight at school, is sent to live with his uncle in Austin for the summer of 1998. At the uncle’s insistence, Nathaniel spends his days volunteering at a nursing home, reporting to the activities director, a charismatic Haitian-born ex-boxer named David Dalice. The two develop an unlikely bond, and David begins training Nathaniel at a local boxing gym. Over the course of the summer, Nathaniel begins to transform. Then he disappears. The Slip is the story of what happened to him.

It is also—and this is relevant for our purposes—far from autobiographical. The book is preoccupied with the lines that typically divide Americans—racial, economic, geographic—and the opportunities and tensions that arise when those lines begin to fade. Among the players connected to the disappearance are a wide and varied cast of Austin characters: an up-and-coming boxer who crossed the border from Mexico under strange circumstances, a rookie cop determined to crack the case, a grifter clown (figurative and literal). The only character who bears any demographic resemblance to me is poor Nathaniel: white and Jewish.

And yet it was Nathaniel who I could never seem to capture on the page. Or, rather, I couldn’t find a way to convey his dreariness with any pep. I knew it was essential for Nathaniel to be inchoate, unsure of who he was. But he became an unformed kid stuck in unformed prose, his scenes as blah and vague as he was. Most of the other characters had, after a year or two, started to take solid form. What was I doing wrong?

I began to consider how I’d developed my other characters. They’d all started as inscrutable amalgamations: pieces of people I’d known and of myself, pieces I’d imagined. Writing characters who were, on the surface, so unlike me, I was acutely aware of the importance of specificity, nailing down their voices and physicality over many drafts. Crucially, I learned to understand them within the context of Austin, the city where I’d spent most of my adult life. I considered the city’s racial and class dynamics, and the history that had created those dynamics, and each character’s history within that history. I knew, two years into the process, exactly where each of them lived and how they made their money and how much.

Most of the other characters had, after a year or two, started to take solid form. What was I doing wrong?

Nathaniel, meanwhile, was a void. In those initial drafts he hailed from suburban Houston, though the adjective was more central to my understanding of that place than the noun. His high school was similar to the suburban high schools in many of the movies and shows I’d grown up with: a generic land divorced from history and politics. In my commitment to creating singular characters in my diverse cast, I’d revealed a subconscious bias: the white character had come from Anywhere U.S.A., a sort of baseline location that didn’t require description or thought.

Of course, a place without history or politics is a place that doesn’t exist. In the end, someone from Anywhere is from nowhere at all.

*

This is when McCracken once again appeared on my shoulder, as our best writing mentors do, unbeknownst to them, for the rest of our writing lives. If you are writing a story and you need a house, she orated, just use your grandmother’s. Use a house you know.

I decided to rewrite Nathaniel’s history by borrowing from my own. I uprooted him from Houston and instead had him hail from my Massachusetts hometown.

To give you a sense of the Newton, Mass. of my nineties youth: during my senior year of high school, a mild controversy developed over at the middle school regarding a bulletin board dedicated to significant LGBT people throughout history. The issue was not, as it might’ve been in other school districts, the existence of the bulletin board, but rather that Eleanor Roosevelt had been included in the display.

When I decided to re-imagine Nathaniel as a Newtonite, these were the sort of memories that began to emerge. The year of the bulletin board, I was one of the editors of the student newspaper; I was also gay and in the closet. The news editor, Rachel, was a closeted lesbian. Together, we were constantly inserting gay content into the paper’s pages, though we never spoke of it, quietly turning The Lion’s Roar into our own version of The Advocate. We plastered the bulletin board story onto the front page, above the fold. Later, we interviewed a local homophobic agitator, an elderly man with an eye-patch whose kindly-old-grandpop speaking style was belied by the words coming out of his mouth. We were ostensibly there to cover recent attacks he’d launched against the existence of gay-straight alliances in area high schools. I think we were mostly just curious to meet him face to face, to see, if we ever did come out, who we might be dealing with.

Why was I in the closet? I suspected that my family would be supportive if I came out; my friend circle was, in hindsight, a gay-straight alliance of its own, all newspaper and theater kids. Our affluent and largely white high school’s emphasis on inclusivity often rang hollow, but it was also sometimes substantive. The faculty included more than one instructor who was out, including Bob Parlin, a beloved history teacher who created the first gay-straight alliance at a public school in the entire country. Our public school. And yet in the closet I remained, along with, in my memory, every other queer kid.

Sometimes, troubleshooting a problem character isn’t about inserting yourself into that person but inserting him into a context you know.

Some of it, of course, had to do with the national landscape during our most formative years. I was in sixth grade when “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” became official military policy. At the start high school, Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act, banning federal recognition of same-sex marriage. Matthew Shephard was murdered our junior year.

But I suspect what made the greatest impression on me was not the landscape but the landscapers. While the reactionary right offered the most frothing anti-gay rhetoric, much of the anti-gay policymaking happened under a Democrat, Bill Clinton. In Newton, where “diversity” was the watchword of the day, almost every adult I knew enthusiastically voted for him.

Even Eleanor-gate, in retrospect, required re-evaluation. Those raising a ruckus over the bulletin board were not out-there Christians or far-right rabblerousers but “regular” Newton people. I’d always viewed the incident as a particularly goofy squabble between relatively likeminded liberals. But the message of the fracas must’ve had an impact on me, even if I didn’t know it at the time. A bulletin board acknowledging the achievement of established homosexuals was fine, but to lump in a vaunted historical figure previously perceived as straight wasn’t a bold act of historical reappropriation, or even a well-intentioned if misguided gesture. It was an insult.

None of this, on the surface, would seem relevant to Nathaniel Rothstein. But in remembering and reconsidering my own high school experience, I was able to imagine the contours of his with a new specificity. Nathaniel wasn’t gay, but in my revised conception, he was a theater kid—a milieu I knew well—an outcast even among the other outcasts on the stage crew. While I was silent about my sexuality, Nathaniel’s deep secret was his love of musicals, and though our reasons for being closeted were different, our reasoning wasn’t. In relocating Nathaniel to Newton, I was also able to glean insights into his views on race—essential for the book—that were not possible for me to understand when he hailed from a blurrier setting. Every city, every school, is its own particular stew of contradictions and complications; in the end, the way I figured out Nathaniel was by dropping him into one that I’d personally supped on.

Sometimes, troubleshooting a problem character isn’t about inserting yourself into that person but inserting him into a context you know. Sitting down to recraft those pages, I could see Nathaniel skulking the buffed corridors, one backpack strap slung over his hunched shoulder, could imagine him enviously eyeing passing packs of more confident-seeming kids. Nathaniel made sense once I understood where he came from, this boy who was still unformed, but also, finally, whole.

________________________________________

The Slip by Lucas Schaefer is available now via Simon & Schuster.

Lucas Schaefer

Lucas Schaefer lives with his family in Austin. The Slip is his first novel.