Love, Death, and the Birds of Terry Tempest Williams

Randon Billings Noble: What of the Raven, What of the Dove?

A story was growing inside my neck, but I didn’t yet know what it said. After the first appointment I started Terry Tempest Williams’s Refuge.

In the weeks between the ultrasound and biopsy, I read about the rise of the Great Salt Lake, the displacement of its birds, the spread of Williams’s mother’s cancer, her slow relentless death.

I read this while I waited.

The first robins of spring arrived, and I pointed them out to my two-year-old twins. They soon became expert at spotting robins. There was one in the mulch under the bush; there was one on the edge of the sidewalk; there was one in the tree outside their window. They looked back at us almost balefully, like portly English gentlemen in wooly red vests, peering out of the 19th century, unsure what to make of our present.

I wonder if Williams, as she identified avocets and counted egrets, knew that the Romans studied birds to determine the will of the gods. That auspice, auger, and avian share a Latin root. Did she seek prophecy in burrowing owls, in snow buntings? Or could she see all too clearly what lay ahead?

What growth to feed and what growth to excise is a matter of perspective.

“Erasure,” Williams writes in When Women Were Birds: Fifty-Four Variations on Voice. “What every woman knows but rarely discusses. I don’t mind erasure if it is done by my own hand.”

She looks at its shades of meaning—to rub out, to eliminate completely, to obliterate, to murder. The word comes from the Latin; it shares a root with raze.

Williams writes in pencil and uses an eraser. But even then, doesn’t a trace remain?

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

You cannot erase a growth. You can excise it, but it is cut—not rubbed—away. Something is missing. An absence is left. What will you fill it with? What substance? What story?

When the Great Salt Lake rose to a record high of nearly 4,212 feet and spread to cover almost 2,400 square miles, it didn’t think, What about the birds in the Bear River Refuge? The tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad? The needs of a daughter losing her mother too soon, too soon?

When a development takes over a hillside, it doesn’t think, What about the land beneath us? The trees we have felled? The animals we have displaced? The water we have diverted?

When a nodule grows on a thyroid it doesn’t think, What about the airway I might threaten? The pressure I might cause? The possibility of cancer I inject?

As almost a joke I unfolded a bird guide—a laminated sheet of maybe 50 one-inch birds—and asked, “Where’s the robin?” My daughter, two years and two months old, looked and looked and looked and pointed. Robin. She was right.

“A mother and a daughter are an edge,” Williams writes.

A sharp edge can cut: the edge of a knife, the edge of a sheet of paper. A round edge smooths the transition from one plane to another: the curve of a torso from ventral to dorsal, the lip of a bowl from inside to out. Regardless of its shape, an edge divides and defines: mother/daughter, healthy/stricken, grafting/pruning, living/dying.

The twins—my daughters—will live beyond me. Their lives are wide open, and they don’t know agoraphobia. My life is not claustrophobic, but it has narrowed narrowed narrowed with each choice.

There’s a danger in living vicariously through your children, but—when they are small—it is impossible to live separate, parallel. We are in this—this life, this dyad, this ecotone—together. I cannot live for them or through them, but I can witness and fuel and follow and lead.

Today I spent an hour listening to recordings of birdsongs. I want to tell them black-capped chickadee and white-throated sparrow and Carolina wren when they ask.

Once you open your ears to birdsong, it is everywhere.

The return of robins forecasts spring. A robin in a bird guide invites identification, learning, a choice made, a path taken, pride.

Birds are sent from ships to shore; canaries are lowered into mines; falcons are loosed to find prey; needles pierce the body to extract an answer.

Four needles, thirty seconds each, in a deep node more than half an inch in. One can think of this with wonder—that so much knowledge can be drawn from such a simple procedure. One can think of this with fear—that four needles will strike, twitch, jerk, push, and draw both blood and bruise. One can try not to think of it at all, to forget once it’s happened, to refuse to count the days as 48 hours stretches into a week.

The raven was sent away and never came back. Did it drown? Did it find land and stay there? What of its mate back in the ark?

The dove returned with an olive branch and, presumably, reunited with its mate. But what of the raven?

The dove came back with a story in its beak. The raven disappeared into silence. When we have flown alone over deep waters, what story do we tell when we return? What stories do those left behind tell if we do not?

It will take a weekend to absorb the knowledge that my story, for now, stops here.

It will take two weeks for the coin-sized bruise in the hollow of my throat to fade from plum to glaucous to yellow to white.

It will take longer than that to believe that my body has finally absorbed the blood and the bruise is gone.

It will take longer still for me to conclude with “The End.”

Are those wings on the horizon? A branch in the beak? Doubt grows in silence and in stealth, while hope circles for a perch.

__________________________________

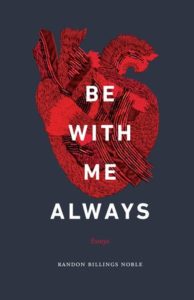

Excerpted from Be With Me Always: Essays by Randon Billings Noble by permission of UNP. © 2019 by Randon Billings Noble. This essay originally appeared in Rappahannock Review 2, no. 3 (August 2015).

Randon Billings Noble

Randon Billings Noble is an essayist. Her collection Be with Me Always was published by the University of Nebraska Press in March 2019, and her anthology of lyric essays, A Harp in the Stars, is forthcoming from Nebraska in 2021. Other work has appeared in the Modern Love column of the New York Times, the Rumpus, Brevity, Fourth Genre, and elsewhere. Currently, she is teaching in the West Virginia Wesleyan low-residency MFA program. She is also the founding editor of the online literary magazine After the Art.