“Don’t be afraid,” the counselor reassured me, “I’ve been briefed on your case and I have a lot of experience in this kind of problem.” Her body language had been arranged to suggest that she was open, but everything else about her told me she was closed. She leaned forward, narrowed her eyes, and asked searchingly: “Do you have a good role model for yourself?”

This question had been preceded by: “Do you have issues at home?” Of course—one had first to be from a broken family before one would even possibly think to romance a member of the same sex. Sixteen-year-old me had been sentenced to hour-long sessions in her airless office till I “got better.” My ailment: I had been “caught in a compromising position.” That was to say, a parent had lodged a complaint because she had spotted me taking a nap on the lap of a spiky-haired basketballer in our all-girls’ school canteen. If this was a compromising position—I was face up in said girl’s lap—I felt very sorry for her spouse. Looking at the counselor smiling patronizingly at me, in her floral suit camouflaging with the floral sofa, I thought that the paragon of nurturing Asian femininity she was trying to model for me was a faded farce.

“Amanda?” the counselor prodded.

There were no visibly queer female public figures out in Singapore back then. Once in a long while, there would be a whispered rumor circulated in the pejorative as regards a certain lawyer, or playwright, or singer, always with the addendum: So wasted! How come! There had only been the one flagrant bisexual, a Eurasian model called Bonny Hicks. A public furore erupted when Bonny declared that she was in love with a female swimming champion. The swim champ took pains to distance herself from Bonny, who took solace in white men and died young in a plane crash, solidifying the age-old narrative that there was no good end in sight for socio-sexual degenerates.

I felt dread and doom for the future I was slowly sliding towards, and what everyone else around me seemed to consider a natural inevitability: make your way to college—being absolutely sure to steer clear of the arts and humanities, which were termed, in Mandarin, 死路一条i.e. “Dead Road One Path”; settle into a stable 9-to-5 job—general consensus being that the civil service was a coveted iron ricebowl you could lean on forever; wed a nice lad—obviously no premarital sex, and ideally at least three inches taller than you and one socio-economic bracket higher than the one you belonged to; make 2.5 babies—the magic median that would save Singapore from her aging population.

None of these trajectories were particularly palatable, but what were my alternatives, and who could a plausible role model be? Pulling back into my lineage as far as I could see, the Asian women I came across in myths and legends left me cold and dismayed: lauded for self-sacrificial nobility and close-mouthed passivity in captivity. Historically speaking, a good Chinese woman was, first and foremost, a daughter who never answered back to her father; then the submissive wife who was seen but not heard by her husband, and finally the celibate widow who waited on her in-laws for the rest of her/their days.

And looking around me in media representation circa mid-2000s, I didn’t see anything particularly comforting or interesting, either. Giddy traditional cisheteronormativity is what it is, whether it’s trampy American suburbia a la Desperate Housewives or prudish Singaporean social realist soap operas like Holland V. How could a scantily-clad Eva Longoria trying to bang her gardener or a dim-witted but kind-hearted Jeanette Aw waiting to be swept off her feet spark anything but horror in me?

*

In the midst of this all, there was one woman who gave me hope.

Her name was Marlene Dietrich. Long dead, she had been born into fin-de-siècle Berlin of 1901. A hundred years later, I had come upon her in a most roundabout fashion. I’d seen The Hours at the mall, and left perplexed. (At that point, I’d read Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, but not Cunningham’s The Hours, so I didn’t know the plot.) Some scenes just didn’t add up—characters who had been self-possessed a moment ago were red-cheeked and flustered a moment later.

After some online sleuthing, I found out that the version that had been screened in Singapore had been censored by our punctilious media authorities. They’d scissored away three lesbian kisses between Nicole Kidman (whom I could not believe for the life of me was playing Virginia Woolf) and Miranda Richardson, Julianne Moore and Toni Colette, Meryl Streep and Allison Janey. Why, I thought, they’d might as well not have even bothered to screen the film at all!

This led me, naturally, to search for the deleted scenes—they were not much of a deal, really—and I ended up going down the time-travel wormhole of YouTube algorithms, till I ended up at a fan collage of Greta Garbo kissing a duchess in Queen Christina and Marlene Dietrich kissing a female diner in Morocco. So it was senseless censorship that brought me to vintage MGM and Paramount movie clips of Garbo and Dietrich snogging women, and for that I have the Media Development Authority of Singapore to thank.

Marlene intrigued me.

In Morocco, she’d kissed a woman and cuckolded a man at the exact same time—how economical!—with a charm that seemed to be played neither to the woman nor the man but to the camera, straight to the beating heart of the viewer. I was soon a Marlene connoisseur; I trawled through well-kept fan blogs, watched whatever old movies I could get my hands on, and read all her biographies. Marlene had a sense of humor, did whatever she wanted, and truly gave zero fucks.

Every anecdote was tinsel I could add to Marlene’s crown: As a teenager in boarding school, she’d landed herself in hot water by sneaking cream puffs into her dorm in her brassiere. Trying out for a non-speaking bit part as an extra in a casino gambling scene early in her career, she went to the audition in velvet gloves, a lacy negligee, and a puppy on a leash, to stand out from the rest of the hopefuls. She was married to one man her whole life, but had intense relationships with other men and women without hiding them from her husband or the press. Her husband had a mistress of his own, too—a woman she had personally introduced to him—and the three on them vacationed together all the time. She spoke her mind freely: “In Europe, it doesn’t matter if you’re a man or a woman—we make love with anyone we find attractive.” “Sex is much better with a woman, but then one can’t live with a woman!” “I am at heart a gentleman.”

Every last thing Marlene did gave me life.

To be sure, it wasn’t all big ticket identity and sexuality. I could count on Marlene’s joie de vivre in the banal and granular, too. I had been told to get a “proper” schoolbag because the patchwork tote I had sewn together from my mom’s old jeans made me “look like a beggar”; I was “flying (my) freak flag really high” for cutting my own hair and leaving it asymmetrical. So what? Marlene had stalked through the streets of Berlin in her own idiosyncratic fashion—wearing a monocle she didn’t need, with swan feathers tied to her purse, in wolf furs that were sold as floor rugs thrown over her shoulders.

People followed Marlene. Some were enamored of her. Others were laughing at her. She laughed right along with them.

Though Marlene existed in a time and space completely unlike my own, the fact that she had lived so fearlessly and fabulously through an epoch where social norms and conventions had been even more restrictive gave me courage to try to move through my world in the here and now just as unapologetically and marvelously. Later, when my best friend bought me a vintage Marlene poster off eBay for my birthday (so gigantic we could hardly find an IKEA frame large enough for it) I lay each night beneath her bone structure like I was recharging from all the injustices of teenage life in a place that didn’t understand any of the things that really mattered.

*

All through the growing pains of my teenage years, I slept under Marlene’s bedroom eyes. Around the time I turned 21, I replaced smoking Marlene with an authentic 1950s Shanghai tobacco ad, wrapped up the frame of my unlikely teenage idol in bubble wrap and stowed her away in the attic. I had outgrown Marlene—I was looking for myself. By the time I moved to New York a few years later, I had forgotten about my Blonde Venus.

The first place I visited upon settling in New York was not MoMA or Central Park or Momofuku or Times Square but the Strand bookstore, and it quickly became a favorite haunt, even if this was a cliché I was playing into as the lost, youngish transplant who wanted to think of herself as a writer. On one of my regular Strand visits, I was browsing through the fine-art photography aisle when an Alfred Eisenstaedt monograph caught my eye.

There was a woman on the cover, looking sated from dinner. She wore black gloves and her face was not without a touch of baby fat. The hair was dark blonde, not the platinum I knew it to be. It was my bygone queen—a younger, more naïve, slightly plump Marlene, as I had never seen her. Rifling through the photobook, my heart started beating faster when I landed on a curious image of young Marlene alongside Anna May Wong, Hollywood’s first Chinese-American film star, and Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler’s cinematic propagandist. They were all at a party in Berlin in 1928. None of them had made their mark on history at that point—they were simply three ingenues looking for their big break. Standing in the aisle at the Strand, a frisson of all things coming full circle ran through me.

I had found Marlene again, or was she the one who’d found me?

When one does not see any plausible future for themselves represented in the media narratives and immediate environments they’re growing up in, self-selected teenage role models become stand-in emblems vested with esoteric power beyond their common veneer. These icons/ikons function as a devotional aid towards self-actualization in an inhospitable place.

I was lucky enough to be able to hold on to me, and I am grateful for the tiny temple I made deep within my innermost self, with Marlene’s unlikely likeness on my altar, which allowed me to beat an untraceable mental retreat even when my body had been forced to sit on an ugly floral sofa, and my ears had to listen to the counselor, who was still painfully pussyfooting around my “issue” (she could not bring herself to say “girlfriend” or “lesbian,” as if once she invoked any of these unholy nouns, I would shed my human schoolgirl exterior and morph into my true demonic state) by asking if I had a role model.

“No,” I lied.

Why should I tell her about Marlene? I could not bring myself to sully my lady’s name in a space that wouldn’t be able to hold her free spirit, her will to be. What could the counselor have seen in this queen, but a loud, lewd, cheating, smoking, foreign, bisexual degenerate? I am, at heart, a gentleman.

________________________________________

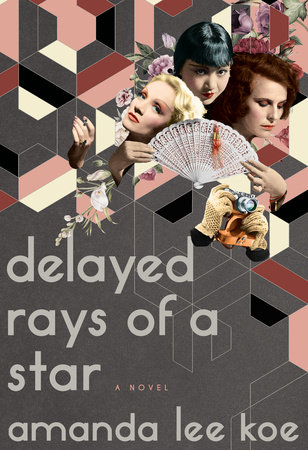

Amanda Lee Koe’s debut novel, Delayed Rays of a Star, is available from Doubleday.