Barbara was late to the meeting, and she rushed to it directly from her job at the call center. It was only after she settled down in her metal folding chair next to the two new-comers that she noticed the socks under her slacks were mismatched: one was navy and one black, a difference she’d been unable to distinguish in the dark that morning. She crossed her ankles and moved them underneath the seat, next to her purse, and tried to pay attention to what Dimsberg was saying, but her mind was distracted by the discovery of the socks—and Chimsky’s phone call that morning, out of the blue, asking her to meet for a drink. Could anyone be more dense?

As she pondered what she’d ever seen in her ex-husband— it had become Barbara’s habit to regard Chimsky as the catalyst of her issues, although a year in the Snoqualmie Chapter of Gambling Help had consistently reinforced in her mind that she was their source—the newcomers sitting beside her suddenly rose, startling her.

“Excuse me,” mumbled the woman, aiming to get out of the circle by moving her chair. A man followed—her husband?

Barbara scooted aside several inches, and the couple had broken through and were mere steps from freedom when Dimsberg’s voice ascended to arrest their escape.

“My friends!” he said. “Stay among us a while longer. You must’ve come for a reason—tell us your story.” He opened his arms magnanimously. Dimsberg was not a charismatic person, with his long face and teeth like a rat’s, but he seemed to have a way of making people do what he wanted, and the couple returned to their seats, although they remained standing.

“What are your names, my friends?”

They said they were Shirley and James Harris. Barbara joined with the rest of the group in welcoming them. “Welcome, Shirley! Welcome, James!” There was, of course, that perverse part of Barbara that wanted to whisper to get the hell out before Dimsberg could get his claws into them.

“We weren’t sure, you know, if we belonged,” Shirley said hesitatingly. “James and I—we don’t gamble every day. Or even every other day.”

“Shirley, one of our mantras is an addict is always an addict. Your very presence in this room is telling.”

“Still—we aren’t sure about this.”

“Tell us why you came,” Dimsberg said. “Why don’t you let us decide?” Other people in the circle encouraged them, and Barbara again found herself in their number. She relished hearing first-timer stories—they satisfied to some degree her desire for action. She admired those in the circle who’d lived through worse than her; conversely, there were some in the circle whom she did not respect for what she felt were minor problems made major. Barbara was curious where this new couple would fall.

It was the woman, Shirley, who spoke. She explained that she and James never went to casinos, and before this past year had never gambled outside of occasional forays into the state lottery, when the amount of the jackpot was too large to resist. They never won anything. Still, they were doing fine. They had enough coming in from their jobs as math teachers to survive, and the children—there were several, Barbara couldn’t tell how many—were out of the house. The mortgage was paid each month, et cetera. They were nice, unassuming people. Everyone in the circle was waiting, like Barbara, in anticipation of some more tantalizing morsel.

“Our youngest, Julia, was always the lucky one in the family,” Shirley said. She placed her arm around her husband’s waist. Sitting so close to them, Barbara could see his neck muscles tense at his wife’s touch. “She kept track of the jackpot religiously, and would let us know whenever it hadn’t been hit in a while. She was always winning small amounts—a hundred here or there, sometimes even a thousand. We dabbled, but she played every week, twice a week, like clockwork. We’d chide her about it. Just as a joke.

“One day,” she continued, “ten months ago this week—we received a phone call from the police. There had been an accident downtown. Julia was walking with her friends. They were celebrating—she’d just found a job. Some maniac drove up on the sidewalk. She—Julia—was pinned underneath the car.” She stifled a sob. “They rushed her to the hospital, but it wasn’t any use.”

Dimsberg told Shirley to take as much time as she needed.

Barbara glared at him.

“I don’t even remember what happened the rest of that week,” Shirley said. Her voice grew quiet. “There were arrangements made on our behalf.” She broke down again.

This time, Dimsberg had the sense to keep his mouth shut.

When she resumed, Shirley’s voice was measured. “We thought we wouldn’t be able to go on. But you know, life makes you. One day, about two weeks after the accident, we were filling up at our normal place. James went inside to pay, and when he came out he had the strangest look on his face. Like he’d heard something wonderful and awful at the same time. Do you want to tell them about it, honey?” He shook his head. His eyes never left the ground. “Okay, I will, then. But stop me if I get anything wrong.

“Apparently, there was a bit of a commotion in the shop. The jackpot had been hit the previous Tuesday—a dozen people had hit it. One of the twelve winning tickets had been purchased from that gas station! Everyone was talking about it. But no one knew who it was, because no one had claimed the ticket yet.

“Like I said, James had this strange look in his eyes when he got in the car and told me. He said he knew who had bought that ticket—Julia—and at first, I told him he was crazy. I didn’t want to believe it. But the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. That was where Julia always bought her tickets. And why wouldn’t someone claim their share of the jackpot? No one forgets to redeem $1.7 million. Unless they couldn’t. Unless they were dead. We never wanted to forget about what happened to Julia— that lost ticket became a symbol to us. It was like a gift she’d left us, James said. It was our responsibility to find and redeem it.”

The woman paused to take a drink of water from a bottle that Dimsberg handed her. Barbara looked around, and everyone was waiting on her next words with rapt attention. “We started by searching her apartment,” Shirley said. “All her old rooms. We became obsessed with finding that ticket. Pretty quickly, things started to get out of hand. We bought an X-ray detector, an infrared camera. We tore the furniture apart. Pried open the floorboards. We looked everywhere a ticket could be. All of Julia’s dear clothes—we ripped open their seams and pockets. But we found nothing. We were sitting in the kitchen one morning, drinking coffee, and James was saying we’d looked everywhere.

“Suddenly I remembered Julia lying in her coffin at the wake, in the suit she’d been wearing the day she interviewed for her new job. It was her only suit. Could she have bought the ticket the same day as her interview? Could the ticket still be inside that suit? I said it was at least possible. I looked over at James and he had that strange look in his eyes again. I was afraid to ask, but I already knew what he was thinking. It was the same thing I was thinking. Forgive us, dear Lord, we’ve both gone a little crazy since Julia left us. James said her spirit was not at rest. Was it possible that we could desecrate our own child’s grave to find that ticket? I firmly believed she wanted us to.” Shirley looked around the circle. “I know how all this must sound to you—!”

“You’re among friends,” Dimsberg said. “There’s no judgment here.”

The husband continued staring down, unmoving. There was only a slight ripple along his jawline as his wife spoke, as if he were grinding his teeth. Shirley held onto him tightly. “That night,” she began—she was almost whispering, and Barbara had to strain to hear—“James and I went back to the grave. We had a bag of tools in the back of our pickup. There were two of us shoveling, but it still took hours. Finally, we got down to the coffin. I remember the sound of James’s spade scraping against the wood, and it seemed to snap me out of my trance. Suddenly, I felt that we shouldn’t be doing this—that what we were doing was wrong, horribly wrong.

“But James said we had gone too far already. I said all right, but you have to do the rest. I turned away and I heard him grunting and prying open the lid of the coffin with the crowbar. I heard the snap as it opened. James was shrieking, and I covered my ears and shut my eyes, and I shouted at him to grab the ticket, grab the ticket! It seemed like hours before I finally heard the noise of the lid slamming closed. When I opened my eyes, James was standing there. He could hardly speak.

“‘Did you get it?’ I said. I could see in one hand he was still clutching the crowbar—and in the other he was holding a slip of paper. It was the ticket!”

Someone in the circle audibly gasped. Barbara realized she hadn’t taken a breath in several moments. She had never heard a story such as this.

“Go on,” Dimsberg said.

“We went back to the gas station the next afternoon.” The life had drained from Shirley’s voice now. “The ticket wasn’t the winning jackpot ticket after all. We told him to check again, and he said that he was absolutely certain that it was not the winning ticket. Julia had only gotten two of the numbers right—but it was still worth fifty bucks.”

The way the woman said “fifty bucks” made Barbara cringe—like they were all victims of some sick joke.

Shirley closed her eyes for a moment. “James hardly speaks anymore, since that night. But I know we’re on the same page. Fifty dollars is far from enough. We play every drawing now, for Julia’s sake. We started buying seven tickets a time, because that was the day she was born. Then we bought seventeen every time, because that was both the month and the day she was born. Then thirty-seven every time, factoring in her birth year and age. Still, we haven’t won. But we know we will if we can just find the right number to buy. Julia is worth more than fifty goddamned dollars.”

Here, the woman fell silent.

“Hey, at least she won,” Dimsberg said. “Lucky Julia, you know?”

Quickly, Barbara rose—feeling everyone’s eyes turn to her—and left the circle. She nearly ran.

Once outside, Barbara leaned her head against the cool brick of the Community Center, smoking a cigarette. No one else came out. She couldn’t believe they could all still sit there, after hearing a story like that. What she needed was to get away from them for a moment. What she needed was a drink, she thought, recalling Chimsky’s offer. She ground the butt to ash on top of the trash bin, and stepped across to the pay phone beside it.

“Okay,” she said into the receiver when he answered. “One drink. Meet me in half an hour at Rudy’s.” When she arrived, ChImsky was already waiting at their usual spot in the back, a small booth for two underneath a mounted moose head, a drink in hand. He was dressed in his dealer’s garb. He rose to meet her, extending his arms in an awkward attempt at a hug, but she patted his arms away gently. “No, Chimsky,” she said. “Sit down.” She pulled out her chair, collapsed heavily on it, and sighed. He looked at her with unconcealed delight.

“Hi, Barbara. I was so thrilled when you called.” “I see you’ve started without me.”

“I was a little nervous,” Chimsky said. “I’m really glad you called, Barbara—but I said that already. How are you doing?” The waiter came by, a young man with wet, spiky hair, and Barbara asked him to fetch her a gin and tonic. After his departure, she sighed again. “To be honest, Chimsky, it’s been hard, fitting everything in. I’m working full-time now. And then going to the meetings.”

“Are they still making you feel terrible about yourself?” Chimsky said. “I never liked—”

“Please,” she broke in. “Don’t start. They provide structure in my life. I was out of control for a long time.”

“But we had a good time,” Chimsky said. “We were good for each other.”

“Stop, Chim. You know that’s not true.” Barbara’s drink was placed in front of her on a tiny napkin; she thanked the server, and he nodded and left. “Let me enjoy this, will you?” She sipped it, relishing its smoothness. “Why don’t you tell me what’s been going on with you?”

Barbara listened to her ex-husband’s recap with only half an ear. Rudy’s was loud at that hour, and Chimsky was describing a series of events that she did not have the desire to understand completely. She looked him over as he spoke, noticing how he had aged, growing thinner, more lined. He was ten years her senior, but the difference had scarcely been noticeable when they’d been married—now, however, she thought he looked in his sixties, despite being fifty-two. No, fifty-three. Chimsky was fifty-three, because she was forty-three. He was explaining to her a hand of Faro, a game she never played, and an old woman who tipped him $5,000—

“Wait, did you say five grand?” Barbara asked. “Yes.”

“How much of that is left? I’m afraid to ask.”

“At least twelve hundred,” Chimsky said. “Business has been slow at the Royal lately, but we still have good nights. You should come by—”

“I told you I hate that place,” she said. The waiter returned, and she ordered noodles—she hadn’t eaten all day, she realized. Chimsky ordered another whisky sour. “Do you ever play the keluaran hk lottery?” she asked after a moment.

“The what?”

“The lottery. The state lottery.”

“I’ve bought a ticket or two,” Chimsky said. “Why?” “Do you ever win?”

“Of course not,” Chimsky said. “You know how much of a scam those tickets are—on average, they return sixty-two cents on the dollar.”

“Never mind,” Barbara said. “Someone was testifying about it tonight in my meeting, and I guess it’s on my mind. I can’t tell you about it, of course.”

“You’ve been thinking about playing it?”

“No. But the new people were so odd and sad. She said they play thirty-seven tickets at a time.”

“They’re wasting their money. They’d be much better off coming into the Royal once a week and betting it all on red.” Barbara laughed. They ordered another round of drinks, and then settled into light reminiscing. Her noodles were delicious. She hardly knew what Chimsky was saying while she ate and listened to the music, which seemed softer now that she’d been drinking, but she found his idle chatter not unpleasant to hear again, after things had been so brutally quiet recently.

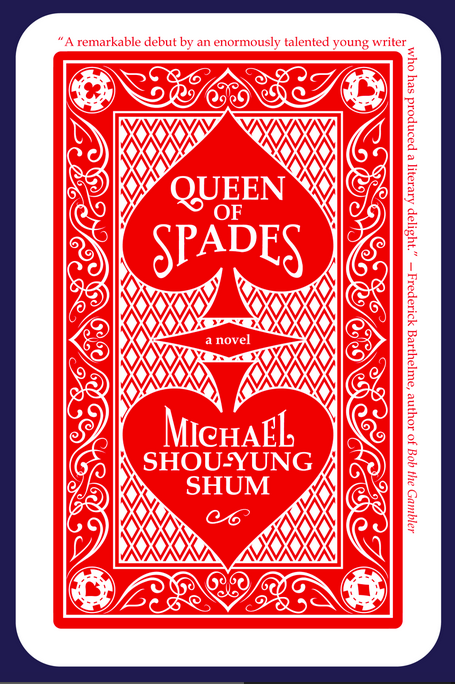

At midnight that night, before separating outside Rudy’s— Chimsky wanted to escort her home, but she said no, firmly— they agreed they should get together again sometime in the vague future. She was too unsteady to drive, so she began to walk in the rain, only about twenty minutes through the silent, wet streets to her apartment. Along the way, she passed a gas station, and she went inside to warm up and get a cup of coffee. In the line at the counter, Barbara broke her usual practice and glanced at the dazzling array of state lottery tickets in the display case. The ingeniously designed Changing of the Card caught her eye. A dealer was depicted with a white-gloved hand poised over a playing card. From the left, the card was the 7 of Diamonds. From the right, it was the Queen of Spades. She hesitated when it came her turn in line. She could break her rules once. No one was watching. She turned to double-check. Then she pulled a five-dollar bill from her purse and bought her coffee, her gum, and one Changing of the Card. She folded the ticket and slid it inside her purse, into the side pocket, and walked home quickly, humming a faint melody underneath her breath.

__________________________________

From Queen of Spades. Used with permission of Forest Avenue Press. Copyright © 2017 by Michael Shou-Yung Shum.