Lost: Joanna Kavenna on Walking the Grande Randonnée

Life, Death, and Sheep in the South of France

Midway through the walk, I was lost. The sun faded and the moon rose, like a fire balloon. I was on a high, windy plateau, dark trees beneath, and then the silent ocean.

All sorts of crazy things go through your head as you walk. I was here for a break. This was quite a few years ago, and I’d been working in London as a temp. I was very bad at my job. Meanwhile there had been a spate of deaths in my family, lots of calls from pensive doctors bearing grim news. Reality felt quite unreal. People vanished, and this was clearly insane, but I was told it was sane and reasonable. I kept waking in the depths of the night, unable to breathe. I wondered if I was going mad.

Everyone told me I needed a break, and sometimes there’s a good reason why everyone tells you something. I took a train to Paris and headed south. I called my boss so he could fire me, which he did. He told me I was lost. I said, “No no, I’ve got a map.” He said, “I mean it as a metaphor.”

This was fair enough. But now I was actually lost. I am very bad at reading maps. Real, metaphorical. Actually all maps are metaphorical, and that’s the trouble! I never quite understand how a neat, fixed representation corresponds to the variable reality around me. This plateau, for example. The glimmering stars, the vast sky. The way the shadows kept sliding along the grass. The way the grass flattened itself, as if it was afraid.

Perhaps this is part of the great randomness. Time is a music that numbs the pain.

There’s a story by Jorge Luis Borges, “Of Exactitude in Science,” in which the cartographers of some fantastical place created ever-larger maps, because they wanted them to be entirely accurate. They hated metaphors. Finally they made a map of the Empire which was exactly the same size as the Empire and “coincided point for point.” But the map was useless, and they had to abandon it in a desert.

But this was hardly the place for stories, fantasies. I was lost, I had to stick to the facts.

I was walking along the Grande Randonnée number 4, from Grasse to the Plateau de Valensole, incorporating the Verdon Gorge.

The Grande Randonnée or Grote Routepaden or Lange-Afstand-Wandelpaden or Grande Rota or Gran Recorrido is a network of walking routes in Europe.

The Grande Randonnée number 4 (GR4) ranges in altitude from 1 to 1,912 meters. My pack contained lots of cheese, bread and water, plus a sleeping bag. It was August; I could sleep outdoors.

The trail would take seven days, then I had to go home and get another job. I was actually (and perhaps metaphorically) lost.

I was reading the map by torchlight when a gust of wind sent it fluttering away. Sometimes it feels as if the universe is proving a point. The battery had died on my phone and I needed the map, even though I was very bad at reading it. I scampered after it, the shadows sliding along with me. I found it again, resting on a tussock. I picked it up, dropped it again, scampered off. It was a funny game to be playing, in the dark. The moon was smiling. My pack felt heavier than before. The barging wind didn’t help. Come to think of it, how many hours had I been walking? Fifteen hours already? My feet were a problem. My boots were old and comfortable but they seemed to have developed a few holes. But all in all, things were fine. It was a clear, warm night. I wasn’t remotely worried about where I would sleep. I was always happy in nature.

I’d begun at Grasse a few days earlier. Many paths lead out of Grasse. I went backwards and forwards for a while and then I marched uphill as fast as I could. There was a long view of the glittering ocean, then the path ducked into a shady forest, birds singing among the gnarled oaks. I thought I heard a lark. As night fell, I crawled into my sleeping bag, not even bothering to move it off the path. I woke again in blazing sunshine, with a family of hikers stepping carefully over my head.

The landscape was dreamlike. Cicadas chirped wildly, everywhere. The loudest insects in the world. My compass kept freaking out. The map—well, I’ve said enough about the map. But it was trouble, always. Day 2 was mostly about tiny flowers and magic. It was very hot, and I had to ration my supplies of water. The flowers were lovely and minuscule. So many variegated colors! I spent the whole day thinking about water. That night I slept at the base of a limestone cliff, in the middle of a circle of boulders. I felt happier being inside the circle; it gave me a feeling of security.

The path forked, over and over again, and often I took the wrong path.

Before I went to sleep I tried to count the boulders—seventeen, or eighteen? Or sixteen? No, definitely seventeen. There was a gap in the circle, like a doorway. I slept deeply, woke at dawn, the last stars fading in the gray sky.

Everything was cold and eerie, the gap had disappeared. Now there was no doorway, just a neat circle of boulders. It made no sense. I wondered if a boulder had rolled down the mountain in the night, and careered into the gap. Or, if the circle was magical. The doorway ensnared foolish travelers. Stone giants ate them. This was impossible, but so many impossible things had happened recently, you couldn’t be too careful. I gathered my things and tiptoed out of the circle. The mountains had craggy, ancient faces. I was certain there had been a gap.

On Day 3 I slept in a forest. My bed that night was very comfortable. I found a pile of moss, and lay down. I was so pleased about that bed. It cost nothing, and the smell of the moss was rich and delicious. No boulders, no gaps. Just the orotund cries of finches. In the morning I saw a heron in a lake, so still I thought it was a figment—then it made a gliding magisterial ascent. I splashed into the lake, gulped down water. Then I filled my bottles again and set off with the heartening sound of my pack sloshing behind me.

Now it was Day 4, and I had been walking for hours, on the path, off the path, back to the path again. I saw a black shadow ahead of me, its shape indeterminate. I thought it might be a refuge, somewhere warm and comfortable. A fire, a bed. I started hurrying forwards, but it became swiftly apparent it was just a ruin. The crumbling walls provided some shelter, so I lay down on the lee side. I was glad to be out of the wind. The sky was full of famous stars and layers of iridescent dust.

I was reading a book by Hubert Reeves, Pourquoi la nuit est-elle noire? The dark night sky proves that the universe is finite. Also, we are made of stardust. When we die, this energy is dispersed into something else. Nothing that has existed can ever truly vanish. It made no sense. I was tired, my French wasn’t good enough.

The wind howled. I was asleep when someone tugged at my foot. I half-woke, assumed it was a dream. Black sky, celestial dust. I couldn’t actually be sleeping in the depths of nowhere, alone. Then I heard a loud, definite rustling and then—worse—the sound of footsteps. Suddenly I was awake and very frightened. “Who’s there?” I said, stupidly. “What do you want?” I said all sorts of stupid things and then with a desperate, trembling movement, I switched on the torch.

I expected—a murderer, a pale lunatic, a moon spirit, the ghost of my father. Instead—sheep! I was so angry with them, for scaring the hell out of me. But they looked miserable, with their little white faces. Like a Greek chorus, masked and anxious. I had stolen their bed. It was the only sheltered place for miles around. “I’m sorry,” I said, still trembling from the shock. “I’m only here for a night.” They stared at me, balefully. “Why not settle down over there?” I said—gesturing towards the opposite wall. It wasn’t as sheltered but it was better than nothing.

Illustration by Blythe Kavenna.

Illustration by Blythe Kavenna.

For a while the sheep stood around, then by some mysterious consensus they gave up and wandered off. I switched off the torch, my heart still pounding. What a ridiculous scene! It took a while before I slept, if timorously, and when I woke again at dawn the sheep had vanished. I hoped they’d had a decent night.

The GR4 has a system of signs, which are very helpful if you read them correctly. A white line over a red line means Follow the Track. The same two lines with a white arrow beneath, pointing left or right, means Change Direction. A red line and a white cross means Wrong Direction. I admired the clarity and simplicity of these signs, even though I often misread them. They referred to tangible objects in space. A landmark. The next village. The right or wrong track. Yet my thoughts were garbled at the time and I often wondered if the signs meant something else. Why did I keep finding myself on the Wrong Track, for example? When the signs said Change Direction did that just mean on the GR4 or in life in general? The path forks constantly, and there are no signs. In life, not on the GR4, where there are always signs. Like anyone, I missed the dead. I couldn’t summon them, except in chaotic memories and dreams.

A brief rest, to stop my thoughts. Misty crags in the distance. Shepherds on the path, dogs barking. The smell of lavender. More finches, bouncing on the air. I filled my bottles in a syrupy stream. A tree had been struck by lightning, its smooth trunk white as bone. There was the sign again, Follow the Track. It was a good path, firm and definite, and it led all the way to the Sublime Point and the Verdon Gorge. Lustrous banks of trees, shimmering sapphire waters. I dined on fish and potatoes, drank Bordeaux, slept in a campsite. Pure bliss. No giants, no ghosts.

The next day I was on the right track and so was everyone else. The path through the Gorge is named after Édouard-Alfred Martel, who carried out geological surveys in the first decade of the 20th century. When Martel arrived, there were no paths at all. He made his own track, which was now the only track. It was hard to imagine this place completely deserted and with no trails or signs. The Gorge was stunning, but it was August and it was full of people. We moved in a sluggish queue, which stalled entirely at the ladders. The rocks were intricately shaped, like Gothic cathedrals. The only exit was far above us.

This gorge was hell—much too hot, rammed with people. But the people were kind in hell even if the place was brutal.

It was hot and claustrophobic. The queue paused at another ladder. I was thinking about water as usual, when I saw a man sitting on a rock. He was wearing a thick brown suit—an odd choice. He was red in the face, leaning forwards, breathing heavily. He looked depressed. When the queue finally moved, I fell in behind him. He walked with his head bowed, he never even glanced at the scenery. Occasionally he mopped his face with a white handkerchief. He took off his suit jacket, slung it over his shoulder. His shirt was soaked with sweat. He had a slender, handsome face, and gray-black hair. Above us—great walls of sculptured rock, people dotted all over them, moving uphill to the exit. I envied these tiny people far above, because they were almost out of the Gorge.

What a strange idea, I thought. Queuing in a kiln, getting boiled alive. For fun. What an experience! Nature worship. I thought of WH Auden, hating mountains. Well, I liked mountains, and windy plateaus, but I hated this boiling gorge. Brown Suit wasn’t carrying a bag; he didn’t even have a bottle of water. I couldn’t bear it any longer. I went up to him, holding out a bottle. Everyone had water apart from him. I said, “Would you like this?” He looked at me, startled, waved his hand, no no, he was fine. Thank you! We carried on in silence, I lost track of time, wondered about Auden and about this man as well.

Eventually I tapped him on the shoulder again and said, in my poor French, “Please take it, I have a lot.” This time he thanked me and seized the bottle, drank almost all of it. He looked dazed. Then a man behind me, a total hiker with all the right gear, offered me a replacement bottle of water. I was really moved by this gesture. I wanted to tell him about the signs, and the heron and the giants and how I’d upset the sheep, but I just thanked him again. Total Hiker said, “I’ll keep an eye on you!” Then he gave his water to the Brown Suit, who accepted it gladly. I thought it was funny, this gorge was hell—much too hot, rammed with people. But the people were kind in hell even if the place was brutal. Perhaps I had heatstroke. Now, thank Christ, the path was climbing upwards, to the exit. The Total Hiker had vanished.

What a strange idea, I thought. Queuing in a kiln, getting boiled alive. For fun. What an experience! Nature worship.

At the top of the Gorge there was the most amazing thing: a little café selling ice creams and drinks. It wasn’t even a mirage. Brown Suit spoke, and asked if I would like a beer. He was called Gabriel. We sat on a bench, drinking our beers and feeling very happy—at least, I was overjoyed. “I’m sorry, I couldn’t speak down there,” said Gabriel. He was a musician from La Rochelle. He was here because his brother often hiked in the Gorge. He died a few days ago, of a heart attack. He was only forty. The shock of his death was so incredible, said Gabriel, that he hadn’t known what to do. So he came here, to be with his brother. I said I was really sorry. “Has it helped?” I asked. Gabriel was confused—my French was not remotely sufficient for this sort of conversation. “I mean,” I said. “I came here, also, because I thought it might help. With my own sense of loss.” That’s what I was trying to say, at least.

“Nothing helps,” said Gabriel. “Except time. Time numbs the pain.” But he said this in a much more elegant way. “Le temps,” he said, “c’est une musique sensible qui engourdit la douleur.” I think this is what he said. We finished our beers and stood. Clumsily, I said that if we met again I would buy him a beer, and he laughed. We both knew that wasn’t very likely. We shook hands and then, unexpectedly, we hugged. His shirt was still soaked. When we parted, Gabriel said, “You go first, you’re faster,” so I thanked him again. Then I went off as quickly as I could, trying to prove him right.

I never saw Gabriel again, not on any of the further paths. I walked along the GR4 for another day or two. Then I took the train all the way back to Grasse, went home, got another job. In a sense, that walk changed my life. But it’s impossible to know for certain. It was just a few days on the GR4, a massive tourist trail. It wasn’t a difficult or remote hike, except I was in such a feverish state.

When I try to write “Grande Randonnée,” my computer types “Grand Randomness” instead. My walk along the GR4 was characterized by great randomness. The path forked, over and over again, and often I took the wrong path. But so many interesting things happened on the wrong paths that I was never sorry I had taken them. My ex-boss and Borges were right. The maps are inadequate. The real journey is imaginary. Gabriel and I were both mired in grief, and yet it was a total coincidence that we ended up in the same part of the queue. Then again, perhaps everyone in the queue was mired in grief, the agony we all carry around with us. Perhaps this is part of the great randomness. Time is a music that numbs the pain, as Gabriel may or may not have said.

And walking is a strange discipline. Your mind charges all over the place. The dead, the living, the stars, the real and the unreal—everything merges and still your body commits to this rhythmic movement. Beating time, onwards. I’m older now and the path still forks. I keep walking, as always.

____________________________

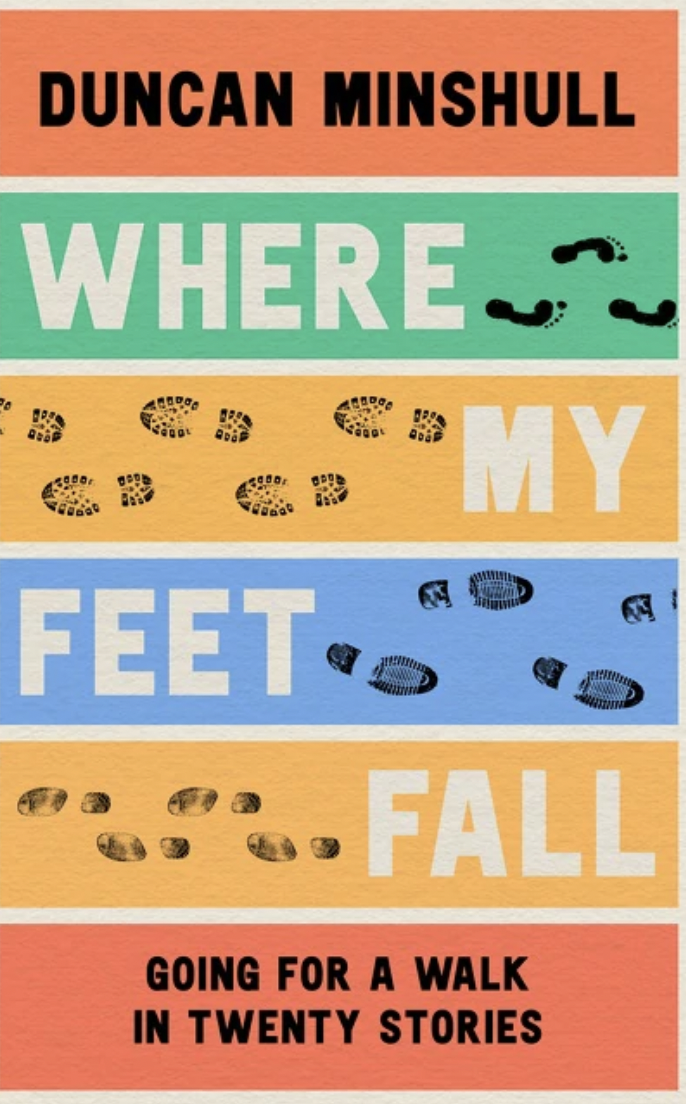

“Lost” was originally commissioned for Where My Feet Fall: Going For A Walk in Twenty Stories, published by William Collins.

Joanna Kavenna

Joanna Kavenna grew up in Britain, and has also lived in the US, France, Germany, China, Sri Lanka, Scandinavia, Italy and the Baltic states. She is the author of several critically acclaimed works of fiction and nonfiction, including The Ice Museum, Inglorious, Come to the Edge, A Field Guide to Reality and, most recently, Zed. Joanna Kavenna’s writing has appeared in The New Yorker, London Review of Books, The New York Times and many other publications. She was named as one of the Telegraph’s Best Writers under 40 in 2010 and as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists in 2013. She has held the Alistair Horne Fellowship at St Antony’s College Oxford and the Harper-Wood at St John’s College Cambridge.