Lost in the Blinding Whiteness of My First Semester of College

Darnell L. Moore on Navigating Life at Seton Hall

Seton Hall University is in South Orange, a short hour and a half drive from Camden, but it was far enough away from home for me to stumble into new experiences and fail outside the watchful gaze of those I feared shaming. It was also close enough to New York City. I had been to New York City only one other time in my life. I was 16 when I traveled to the Statue of Liberty and the fabled Mamma Leone’s restaurant, a once-popular eatery in Manhattan’s Theater District. It was a trip organized by the summer youth entrepreneurship-training program Camden public schools offered in the 1990s. As I prepared to move onto campus, I held fast to my hopes of returning to the place big enough where the hyper-visible could be unseen, a place so worldly one could sin over and over again without the condemning stares that tend to be cast upon anyone who chooses to live as they will. The skyscrapers and packed streets, the people who appeared to be raptured by wanderlust, those seeking to be discovered and those who walked about as if they did not want to be found, drew me in. I would one day roam those same streets, but until then the gated campus of Seton Hall would have to do.

We arrived in Newark, New Jersey, in the early afternoon of move‑in day with bags full of my belongings. It was a humid early summer day in ’94. The sounds of overworked commuters, train announcements, and incoming public buses filled the air. My Aunt Barbara and I searched for signs leading us in the direction of the number 31 bus. We’d already been traveling for two hours, on the bus in Camden and on the train to Newark. Unlike others traveling to campus to begin a summer academic enrichment session meant to prepare students accepted through the Equal Opportunity Program (EOP), my family did not own a car. It was the second time I realized that our family lacked wealth. The first time, I was walking onto the campus of Mullica Hill Friends School, another microcosmic world where white middle-class and upwardly mobile black people sent their kids.

I was no stranger to long commutes, but the commute to Seton Hall made me more anxious than ever. I was moving away from Camden for the first time to a part of New Jersey I never imagined existed. Newark is a black city like Camden, but its spirit is animated, improvisational, and alive like jazz. The familiar tunes of Biggie Smalls and Craig Mack weren’t as dominant as the house music blazing from the speakers on vendors’ tables on Broad and Market Streets, where mix tapes with strange house beats like the “Percolator” and “Witch Doctor” were sold. Newark was a different world, a different hood, where people talked with a different tongue. The sound of the “r” was stronger, harder, as it rolled out of the mouths of the bold, hopeful, and aware black people from Brick City who seemed no less overcome by the looming presence of police and state neglect than those of us who grew up in Camden. Such is the illusion that shapes great escapes from home. The places I’ve run to seemed to always figure as mythical havens of possibility even if they were gripped by the same conditions that zapped hope out of the people and city I tried to abandon. Newark was no different. In fact, I would soon learn why black cities like Newark weren’t that different in many ways from Camden.

My first year in undergrad was typical of that of any black 18-year-old from the hood dropped off and left alone with his bags and pipe dreams on the campus of a predominantly white university. And it wasn’t just any predominantly white university; it was a Roman Catholic one, which meant I would need to prepare myself to face isolation and moral judgment for loving weed and men. White students, staff, faculty, and priests blanketed the campus from the dorms to the classrooms. Those of us who came through the EOP spent way too much time in the small EOP office because it was the one place where we knew other black and Latino students and staff would be. The university green sat at the heart of the campus, and during the welcome orientation it resembled an indie music festival where abundantly cheery white college students would meet up to eat medium-rare hamburgers and drink beers while the sun turned their skin red and scaly.

I registered for classes—a few I liked, a handful I skipped, and others I withdrew from. Even after graduating from a Camden middle school where I excelled as an “academically talented” student, struggling through two years of a private high school, being voted Camden High School’s “Most Likely to Succeed” as a senior, and completing the EOP’s summer program at Seton Hall, I was not prepared for a white campus. I hadn’t learned how to navigate this strange world where white people’s cares and well-being were centered.

“A world away from Camden, with little less than a year in the belly of a predominantly white campus, I had begun the process of a new becoming. I was becoming politically black: aware, awake, in love with my people, and enraged by racial injustice.”

No summer enrichment session I attended gave any indication that a white security guard would grab me and slam me to the ground. I was not taught to expect that a white baseball player throwing snowballs in front of our dorm during a late-night fire alarm would hit me in my face with a large piece of ice while he played. He had a black eye, and I was glad my fist would be remembered as the source. But it was no salve for the wounds to the soul resulting from racial profiling so normalized on a college campus. I felt as if justice, even at a Catholic university, was a concept that only made sense as a theory in philosophy and religion classes.

EOP counselors reminded us constantly to always sit in the front of the classroom, an effort to prepare us nonwhite students for academic success amid the prevailing presence of white peers and instructors. But cues and tips cannot replace the inner power you must summon, which gives you the courage to speak up (even when you don’t have the energy) almost every time a white student or professor makes a racist claim they know to be truth. No words, no workshops, no constant reminders can distort your gaze such that you don’t see that a majority of the students in the cafeteria are sitting and eating together, and they are all white. And the small pockets of black, Latino, and Asian students are cordoned off in small sections of tables. It might have been a scene from Higher Learning, John Singleton’s cinematic take on racial division on predominantly white campuses, which came out in 1995, my second year at Seton Hall. Singleton’s fictional account was too real and too right about a phenomenon so many nonwhite students at Seton Hall knew was unjust.

I had no living room full of black family members who would know I was hurting from loneliness just by looking in my eyes, no kin I could lean on who would remind me I belonged when I felt as if I did not deserve to be on the campus of a college I had put little effort into applying to. But their absences, amid the presence of the daunting reality of living black and free on a mostly white campus, forced me to shape-shift and fight.

By the end of my first year, I had helped reestablish the African Student Leadership Coalition with two first-year black girls, Tia and Kathy. We wanted our quest for respect and equity as black students at Seton Hall to extend beyond rants preached to the proverbial choir about the university’s underrepresentation of black students, professors, and black student–centered groups and programs. I even ended up on Broad Street, the same street I walked on when I first traveled to Seton Hall with my Aunt Barbara, in Newark that year, but this time around I was one of a few dozen attendees packed in a discreet room in a barely finished building listening to black political prisoner and radical journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal. He shared his analyses of white supremacy, black politics, and incarceration by telephone. I was struck by his measured tone and enticing voice. Abu-Jamal was involuntarily isolated, restricting his ability to move past the door to his small prison cell in Pennsylvania. If Abu-Jamal’s spirit could fly free in the midst of forced isolation, I was certain my black peers and I who willfully applied to Seton Hall could soar amid the restrictive whiteness of our university.

All of my life I had identified as black even if I sometimes, with or without awareness, distanced myself from black people I deemed too hood and poor even as others distanced themselves from me for the same reason. A world away from Camden, with little less than a year in the belly of a predominantly white campus, I had begun the process of a new becoming. I was becoming politically black: aware, awake, in love with my people, and enraged by racial injustice. I cared less about perfecting the appearances I had been taught to perform most of my life. I lost interest in those negotiations: displaying intelligence, knowing and staying in my place, quieting my voice, downplaying my street smarts so white people would not interpret me as a threat.

I changed—for better and worse. I walked around campus the first two years dressed in baggy gear and the hottest kicks I could purchase with the money left over from my many student loans or with credit cards I used without care. I cussed loudly, acted tough, and smoked blunts—all were tactics I employed to distance myself as far as possible from the white kids who walked past as if I were invisible and the black students who would remind me that niggas from Camden were worse off than all the rest. With pride, I would brag about Camden. Almost overnight, I had become the thing I was told to resist, a representation of the black thug from the hood. It was the one script I was most familiar with and the one I thought would protect me from white ignorance and set me apart from the black students whom I thought looked down on me for being less smart and not as refined as the rest. My act was deliberate, a survival tactic meant to protect me from the threat of erasure and homophobia. As long as my peers knew I could beat the hell out of white supremacy and white boys, and as long as they knew I could manipulate and fuck around with girls with more cunning sophistication than the other black boys, I knew I’d fare better than I had in high school. I was wrong. Even my avatars could not shield me from the inevitable onslaught of finger pointing and antagonism that accompanies difference.

__________________________________

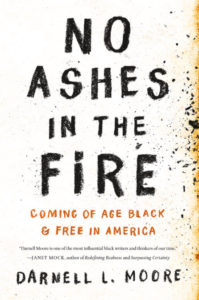

From No Ashes in the Fire: Coming of Age Black and Free in America. Used with permission of Nation Books. Copyright © 2018 by Darnell L. Moore.

Darnell L. Moore

Darnell L. Moore is the author of No Ashes in the Fire. He writes regularly for Ebony, Advocate, Vice, and Guardian. Moore was one of the original Black Lives Matter organizers, organizing bus trips from New York to Ferguson after the murder of Michael Brown. Moore is a writer-in-residence at the Center of African American Religion, Sexual Politics, and Social Justice at Columbia University, has taught at NYU, Rutgers, Fordham, and Vassar, and was trained at Princeton Theological Seminary. In 2016, he was named one of The Root 100, and in 2015 he was named one of Ebony magazine’s Power 100 and Planned Parenthood’s 99 Dream Keepers. He divides his time between Brooklyn and Atlanta.