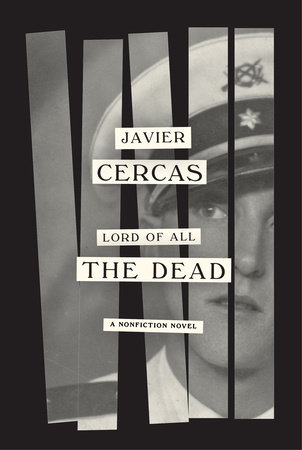

His name was Manuel Mena, and he died at the age of 19 in the Battle of the Ebro. It was September 21, 1938, towards the end of the Spanish Civil War, in a Catalan village called Bot. He was an enthusiastic supporter of Franco, or at least an enthusiastic Falangist, or at least he was at the beginning of the war: that was when he enlisted in the Third Bandera of the Cáceres Falange, and the following year, having recently attained the rank of provisional second lieutenant, he was posted to the First Tabor of Ifni Riflemen, a shock unit belonging to the Corps of Regulars. Twelve months later he died in combat, and for years he was the official hero of my family.

He was my mother’s uncle on her father’s side, and she has told me his story countless times since I was a boy, or rather his story and his legend, so often that even before I was a writer I thought I would have to write a book about him one day. I discarded the idea as soon as I became a writer; the reason is that I felt that Manuel Mena was the exact paradigm of my family’s most onerous legacy, and telling his story would not only mean taking on his political past but also the political past of my whole family, which was the past that most embarrassed me. I did not want to take that on, I did not see any need to, and much less to discuss it at length in a book: it was enough to have to learn to live with it. Besides, I wouldn’t have even known how to start telling that story: should I have stuck strictly to reality, to the truth of events, supposing that such a thing were possible and that the passing of time had not opened impossible-to-fill gaps in Manuel Mena’s story? Should I have mixed reality and fiction, to plug up the holes inevitably left by the former? Or should I have invented a fiction out of reality, even though everyone might believe it was true, or in order for everyone to believe it was true? I had no idea, and my ignorance of the form seemed to be an endorsement of my decision on the content: I should not write the story of Manuel Mena.

A few years ago, however, that old refusal seemed to enter into a crisis. By then my youth was far behind me. I was married and had a son; my family was not going through a great time: my father had died after a long illness and, after five decades of marriage, my mother was still having difficulty adjusting to the thankless stage of widowhood. My father’s death had accentuated my mother’s natural propensity to melodramatic, resigned, and catastrophic fatalism (“Oh, son,” was one of her most well-worn maxims, “may God not send quite as many sorrows as we’re able to bear”), and one morning a car struck her on a crosswalk; the accident was not particularly serious, but my mother got a bad scare and found herself forced to remain seated in an armchair for several weeks with her body covered in bruises. My sisters and I urged her to leave the house, took her out for meals and excursions and took her to her parish church for Mass. I won’t forget the first time I went with her. We had walked the hundred yards between her house and the Sant Salvador parish church, and, when we were about to cross the street at the crosswalk, she squeezed my arm.

“Son,” she whispered, “blessed are those who believe in crosswalks, for they shall see God. I was just about to.”

During that convalescence I visited more frequently than usual. I often even stayed overnight, with my wife and son. The three of us would arrive on Friday afternoon and stay until Sunday evening, when we went back to Barcelona. During the day we talked or read, and in the evening we watched films or television programs, especially Big Brother, a reality show my mother and I loved. Of course, we talked about Ibahernando, the village in Extremadura from which my parents had moved to Catalonia in the 60s, as so many people from Extremadura did in those years. I say, “of course,” and I understand I have to explain why I say that; it’s easy: because there is no event as significant in my mother’s life as emigration. I say there is no event as significant in my mother’s life as emigration, and I understand I should also explain why I say that; this is not so easy. Twenty years ago I tried to explain it to a friend by saying that overnight my mother went from being the privileged daughter of a patrician family in small-town Extremadura, where she was everything, to being not much more than a proletarian or a little less than a petit-bourgeois housewife overwhelmed with children in a Catalan city, where she was nobody. As soon as I had formulated it, the answer struck me as valid but insufficient, so I wrote an article titled “The Innocents,” which still seems the best explanation I know how to give of this matter; it was published on December 28, 1999, Feast Day of the Innocents and 33rd anniversary of the date my mother arrived in Gerona. It goes like this:

The first time I saw Gerona was on a map. My mother, who was very young then, pointed to a faraway spot on a paper and said that was where my father was. A few months later we packed our bags. There was a very long trip, and at the end a rustic, crumbling station, surrounded by sad buildings wrapped in a mortuary light and mistreated by the pitiless December rain. My father, who was waiting for us there, took us out for breakfast and told us that in that impossible city they spoke a language different from ours, and he taught me the first sentence I ever spoke in Catalan: “M’agrada molt anar al col·legi” (I really like going to school). Then we all piled into my father’s Citroën 2CV and, as we drove to our new home through the hostile desolation of that foreign city, I am sure that my mother thought and did not say a phrase she thought and said every time the anniversary of the day we packed our bags came around: “¡Menuda Inocentada!” (What a dirty trick!) It was the Feast Day of the Innocents, Holy Fools’ Day, and she must have felt like a practical joke had been played on her, 33 years ago.

I don’t know if those who pack their bags ever go home again; I fear not, among other reasons because they will have understood that return is impossible.The Tartar Steppe is an extraordinary novel by Dino Buzzati. It is a slightly Kafkaesque fable in which a young lieutenant named Giovanni Drogo is posted to a remote fortress besieged by the steppe and the Tartars who inhabit it. Thirsting for glory and battles, Drogo waits in vain for the arrival of the Tartars, and his whole life is spent waiting. I’ve often thought that this hopeless fable is an emblem of the fates of many of those who packed their bags. As many did, my mother spent her youth waiting to go home, which always seemed imminent. Thirty-three years went by like that. As for others among those who packed their bags, things weren’t so bad for her: after all, my father had a salary and a fairly secure job, which was much more than many had. I think that my mother, all the same, never accepted her new life and, shielded by her all-consuming work of raising a large family, lived in Gerona doing as much as possible not to notice that she lived in Gerona, rather than in the place where she’d packed her bags.

That impossible illusion lasted until a few years ago. By then things had changed enormously: Gerona was a cheerful and prosperous city, and its station a modern building with very white walls and immense windows; apart from that, some of my mother’s grandchildren barely understood her language. One day, when none of her children lived at home anymore and she could no longer protect herself from reality behind her all-consuming work as a housewife, nor evade the evidence that, 25 years later, she was still living in a city that even now was foreign to her, she was diagnosed with depression, and for two years all she did was stare dry-eyed and silently at nothing. Perhaps she was also thinking, thinking of her lost youth and, like Lieutenant Drogo and like many of those who packed their bags, of her life used up in futile expectation and perhaps also—she, who has not read Kafka—that all this was a huge misunderstanding and that this misunderstanding was going to kill her. But it didn’t kill her, and one day when she was beginning to emerge from the pit of the years of depression and was going to see the doctor with her husband, a gentleman opened a door and held it for her, saying, “Endavant,” which means “after you” in Catalan. My mother said: “To the doctor.” Because my mother had understood “¿Adónde van?,” “Where are you going?” in Spanish. My father says that at that moment he remembered the first sentence that, more than 25 years earlier, he had taught me to say in Catalan, and also that he suddenly understood my mother, because he understood that she had spent 25 years living in Gerona as if she were still living in the place where she had packed our bags.

At the end of The Tartar Steppe the Tartars arrive, but illness and old age prevent Drogo from satisfying his long-postponed dream of confronting them. Far from the combat and the glory, alone and anonymous in the dingy room of an inn, Drogo feels the end approaching and understands that this is the real battle, which he had always been waiting for unwittingly; then he sits up a little and straightens his military jacket a little, to face death like a brave man. I don’t know if those who pack their bags ever go home again; I fear not, among other reasons because they will have understood that return is impossible. I don’t know either whether they sometimes think that life has passed them by as they waited, or that this has all been a terrible misunderstanding, or that they’ve been deceived or, worse, that someone has deceived them. I don’t know. What I do know is that in a few hours, as soon as she gets up, my mother will think and maybe say the same phrase she’s been repeating for 33 years on this same day: “¡Menuda Inocentada!”

That’s how my article ended. More than a decade after it was published my mother still hadn’t left Ibahernando even though she was still living in Gerona, so it is logical that our foremost pastime during the visits we paid her to alleviate her convalescence consisted of talking about Ibahernando: more unexpected was that on one occasion our three foremost pastimes converged into one and the same. It happened one night when we all watched L’Avventura, an old Michelangelo Antonioni film. The film is about a group of friends on a yacht trip, during which one of them goes missing; at first everyone searches for her, but they soon forget about her and the excursion goes on as if nothing had happened. The static density of the film quickly defeated my son, who went to bed, and my wife, who fell asleep in her chair in front of the television; my mother, however, outlasted the almost two and a half hours of black-and-white images and dialogues in Italian with Spanish subtitles. Surprised by her endurance, when the film ended I asked her what she’d thought of what she’d just seen.

“It’s the film I’ve most enjoyed in my whole life,” she said. If it had been anyone else, I might have thought it was a sarcastic answer; but my mother does not do sarcasm, so I thought the lack of incidents and endless silences of Big Brother had trained her perfectly to enjoy the endless silences and lack of incidents of Antonioni’s film. What I thought was that, since she was accustomed to the slowness of Big Brother, L’ Avventura had seemed as frenetic as an action movie. My mother must have noticed my astonishment, because she hurried to try to dispel it; her clarification did not entirely belie my conjecture.

“Of course, Javi,” she explained, pointing to the television. “What happened in that film is what always happens: someone dies and the next day nobody remembers him. That’s what happened to my uncle Manolo.”

Her uncle Manolo was Manuel Mena.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Lord of All the Dead by Javier Cercas. Copyright © 2017 by Javier Cercas. English translation copyright © 2019 by Anne McLean. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.