Looking to Songs and Sermons to Structure a Memoir About Fighting for Black Lives

Andre Henry on Pulling from the Genres that Shaped His Life

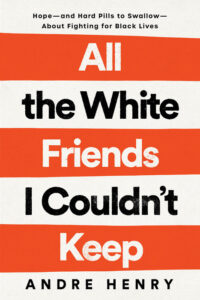

The adage to “write what you know” could be a meta-principle. We know it applies to the content of our writing: that we use our lived experience as a well of inspiration. But the process of writing my memoir, All the White Friends I Couldn’t Keep: Hope and Hard Pills to Swallow About Fighting for Black Lives, has convinced me the principle applies to form as well.

I didn’t intend to write a memoir. I meant to write a letter—a blog, really—addressed to white friends I once considered as close as family, to defend myself against their accusations that I’d become a race-baiting heretic calling for a war on white people. There is, of course, a story too long to tell in the space allotted here behind that accusation.

Suffice to say, I had been doing a lot of creative activism to bring attention to the anti-Black violence that has structured American life since its founding. I was writing songs, creating vlogs, writing articles, and even lugged a hundred-pound boulder around Los Angeles for a few months to demonstrate the weight of systemic racism on the Black psyche. My activism caused an irreparable rift between those white friends and I, as they accused me of encouraging anti-white hate.

Determined to counter their accusations with a receipt of my love, I woke before the sun one morning and sat beneath the orange light hung over my dining table. Blood raced to my palms as I considered what I was about to do, but the tension in my forehead seemed to promise it would leave if I just set the record straight—publicly, in writing—once and for all. “To All the White Friends I Couldn’t Keep,” I click-clacked on my keyboard, then I laid out my case, written more like an impassioned ex than a lawyer, of how our relationships crumbled at the color line.

The blog went viral. A week later, I was on the phone with the man who would become my literary agent, Steve Ross. Steve believed the blog could be expanded into a book. I didn’t see how, but I was willing to try.

Finding the right structure was my greatest challenge. From the start, Steve and I envisioned a kind of literary mashup of memoir and manifesto. We just had to find the right balance of narrative and theory.

At first, I thought I’d structure the narrative along the lines of the hero’s journey I learned in high school, with a long narrative arc that stretched from beginning to the end. I envisioned the first few chapters would involve a good deal of exposition, and that I would begin by immersing readers into my world growing up in the South.

Then, after becoming deeply invested in the characters, they’d follow those relationships through the inciting incident—the killing of Philando Castile by Minneapolis police—and their hearts would break with mine at the climax of the story, when I start ending relationships with white friends who refused to be allies with me in the fight against the racist forces that too often result in tragedies like Castile’s death. With the narrative so far in the forefront, the theoretical work would be subtle, contained in passing remarks on the events I retold, with not much straightforward commentary.

That approach didn’t work, largely because the narrative was moving too slow and without letting the reader know where it was going. I wrote about four versions of the chapter samples that went into my book proposal. All of them suffered from the same problems. The narrative seemed to meander without answering the essential questions a reader asks, even if subconsciously: Why are you telling me this story? What’s in it for me?

In hindsight, I can see that part of my problem was that I was paying so much attention to the long arc of the entire book that I neglected to consider the smaller, supporting arcs that the narrative needed to stand. The other part of the problem was I was not a student of memoir and didn’t have a deep well of knowledge of the genre to draw from, nor the time to become one now that the iron of my writing was hot. Instead of pretending to be a memoirist, I decided to draw from the writing genres from which I have the most experience to tell my story: songs and sermons.

We have more in our literary palettes to pull from than the content of our life experiences—the specific people, places, and things we’ve encountered in the world to create characters and worlds of our own.

I’ve been writing songs since I was eight years old, and I was a teaching pastor in New York City for seven years. I’ve written countless songs and sermons and studied the craft of writing both. I decided that song and sermon structure would make up the mini-arcs—the chapters—that support the larger structure of my story. Combining what little mastery I held of memoir and narrative writing with my expertise in songs and sermons, I hoped to create a polemic that sings.

Every great song has a hook—that is, a main idea made memorable through melody and repetition. Hit songs often include the hook in the title. The hook in a song like Billy Joel’s Uptown Girl or Snoop Dogg’s Drop It Like It’s Hot is obvious, in part, because the hook is in the title, and the melody for those words has to be an absolute earworm.

I tightened the structure for each chapter of my memoir by figuring out the hook: what is the main idea and how do you make it as memorable as a melody? I want that idea ringing in my reader’s head like a pop song they can’t stop humming. A music mentor once told me that a song title needs to read like a bumper sticker: it needs to be reactive and intriguing. And that became a goal of my chapter titles, with titles like “We Do Not Debate With Racists” or “The Whole World Is Stone Mountain.”

The format for how I would lay out my ideas in each chapter came directly from a modified version of one of my most often-used sermon structures. It is a linear style that starts with a story of joke that draws the audience in, then dissects a biblical text, then, from that exegesis, draws an abstract universal principle, then applies that principle to the specific context of the audience in front of the preacher. For each chapter, a story from my life that illustrated the point about racial progress became the sermon illustration, I exegete my experience using history and social movement theory instead of dissecting a biblical text to draw out universal principles, then I apply that principle to the struggle for Black freedom.

I still had to work with tools less familiar to me for the long arc of the book, like character development and plot. However, constructing the mini-arcs of the long narrative with the tools of sermon and songwriting made each chapter much more rewarding to read—and to write.

All of this to say we have more in our literary palettes to pull from than the content of our life experiences—the specific people, places, and things we’ve encountered in the world to create characters and worlds of our own. We also have the many forms of expression we’ve encountered or tried, other art forms we’ve dabbled in, or maybe even just some obscure, arcane theory or concept from some class we took in college, to help us structure the stories we want to tell.

_____________________________________________________

Andre Henry’s All the White Friends I Couldn’t Keep is available now via Convergent Books.

Andre Henry

Andre Henry is an award-winning musician, writer, and activist. He is a columnist for Religion News Service and the author of the newsletter “Hope and Hard Pills.” He is a student of nonviolent struggle, having organized protests in Los Angeles, where he lives, and studied under international movement leaders through the Harvard Kennedy School. His work in pursuit of racial justice has been featured in The New Yorker and The Nation, and on Liturgists Podcast.