Looking for Paris's Old Left Bank in the Footsteps of Simone de Beauvoir

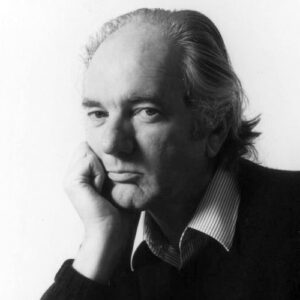

Marta Bausells in Conversation with Agnes Poirier

“I’m not a writer,” Agnes Poirier quickly clarifies before we set off on a walk around Saint-Germain-des-Prés; “I’m a journalist.” It’s a distinction that is perhaps more important, more relevant in France than in America. Literature here is still considered high art, easily tainted by commercialization. For many “serious” publishers it is tasteless, even, to design book covers beyond an austere monochrome feature the title in simple type, as the shop windows of many a bookstore on the Rive Gauche attest.

We walk past Les Deux Magots, Sartre’s mother’s apartment (where a lot of the Les Temps Modernes all-nighter editorial meetings were held), Richard Wright’s apartment (majestic and big, so different to the rest of the artists’—to the French, he “was not black, he was simply rich, well fed, and American”), Picasso’s studio, and the original location of Sylvia Beach’s legendary Shakespeare and Company bookstore.

Poirier shows me how, “Paris being Paris,” the places about which she writes are still practically intact—even if some of the interiors have been converted into boutique or luxury establishments. She says: “because it’s the past, because they’re intellectuals, and because I’m French, I thought it would be a book purely about intellectual history. Something a bit abstract, probably too dry.” But one can touch the walls. “So suddenly it’s a question of sensuality, there’s the sense that you share the touch,” she says.

*

It was the details of the flesh that captured Poirier when she set out to write a book about artists and thinkers in Paris during and after the Second World War. It was the food they ate, the clothes they wore, the sex they had, the pens they used—in the case of Simone de Beauvoir, a green ink fountain pen. On Thursday, May 16, 1946, de Beauvoir wrote, as was later captured in her autobiography The Force of Circumstance:

Spring is coming. On my way to get cigarettes, I saw beautiful bunches of asparagus, wrapped in red paper and lying on the vegetable stall. Work. I have rarely felt so much pleasure writing, especially in the afternoon, when I come back at 4:30 pm in this room still full of the morning’s smoke. On my desk, sheets of paper covered in green ink. The touch of my cigarette and pen, at the tip of my fingers, feels nice. I really understand Marcel Duchamp when, asked whether he regretted having abandoned painting, he replied: “I miss the feeling of squeezing the paint tube and seeing the paint spilling on to the palette; I liked that.”

I can just about picture de Beauvoir in that smoke-filled room, and the feeling of the pen in her hand—which is fitting, as I’m meeting Poirier below the very hotel window de Beauvoir might have gazed from as she contemplated those lines. We’re having espressos in front of the family-run Hotel La Louisiane, where de Beauvoir lived between 1943 and 1948 (so did Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Juliette Gréco and many other artists, at one point or another). In the top-floor room, she also had the epiphany that would lead to the crucial feminist work The Second Sex (“It was a revelation. This world was a masculine world, my childhood was nourished by myths concocted by men, and I hadn’t reacted to them in the same way I would have done if I had been a boy.”)

Left Bank: Art, Passion and the Rebirth of Paris, 1940-1950 charts the ups and downs of several generations of revered artists from around the world, whose lives intersected in Paris in that momentous decade of war, emancipation and reckoning. It includes American artists like James Baldwin, Alexander Calder, Miles Davis and the wonderfully lucid Janet Flanner, the New Yorker’s Paris correspondent, who used an old Remington typewriter and whose observations pepper the book. Through the smaller human moments, Poirier’s writing feels like she really was a fly on the wall.

“Despite (or because of) the economy and shattered living conditions, there was an explosion of sexual euphoria. At the center of it were de Beauvoir and Sartre.”

For example, when Flanner goes back to Paris at the end of the war, we learn that she has decided to move into a hotel, along with fellow correspondents, attracted by the fact that she can have a hot bath there between eight and ten every morning, the whole city still “living largely on vegetables [carrot and parsnip] and mostly without heat.” She also bumps into Ernest Hemingway who, inconveniently, has just broken the news to Flanner’s girlfriend about her current Italian lover. Not cool, Ernest.

Pleasurable as they are to the curious reader, it’s not just the daily anecdotes that make the book. Shortly after the Hemingway detail, Flanner took the métro to the Gare de Lyon, where the first contingent of women prisoners were expected to arrive by train. There were 300 of them, and they’d been interned at the Ravensbrück concentration camp north of Berlin. The Allies had crossed the Rhine and were starting to reach many of the concentration camps, and war prisoners and deportees were slowly arriving back home.

In what is one of the most affecting scenes in the book, Flanner took a place “among the crowds awaiting their loved ones with timid smiles and welcoming bouquets of lilacs and other spring flowers.” Among them was Charles de Gaulle, standing alone, “the incarnation of heroic Free France welcoming back to its bosom all those betrayed by cowardly Vichy France—a poignant task,” writes Poirier. His 24-year-old niece, a résistante since the beginning, interned at Ravensbrück, was not in the convoy.

As the women leaned out the windows of the train, the crowd froze in horror: “Their flesh had a grey-greenish halo and all had red-brown circles around eyes that seemed to see but not take anything in,” writes Poirier. Many of the women suffered from dysentery, and were covered with typhoid lice. The crowd began moving, anxiously looking for their loved ones; De Gaulle walked toward the women and started shaking their hands. “There was almost no joy; the emotion penetrated beyond that, to something near pain,” writes Flanner. These 300 women had been selected by the commanders back in Germany because they were the most “presentable.” Eleven had died en route. Flanner observed: “As the lilacs fell from inert hands, the flowers made a purple carpet on the platform and the perfume of trampled flowers mixed with the stench of illness and dirt.”

When the hazy post-war period sets in, Poirier writes:

Unlike London or New York, Paris had faltered, it had sinned. In 1944 the monuments and buildings of Paris may have been riddled with bullet holes, but its physical scars were insignificant in comparison with London’s open wounds, where whole neighborhoods had been wiped from the map during the Blitz. Paris had been spared because France had capitulated, yet the pain ran deeper for the cowards than for the brave. Paris owed its untouched beauty to mental defeat.

The liberation had two effects for artists and intellectuals, the exiles slowly returning to the city. The first: despite (or because of) the economy and shattered living conditions, there was an explosion of sexual euphoria. At the center of it were de Beauvoir and Sartre, who had a well-documented open relationship, with people left and right sleeping and falling in love with either or both of them.

The second brings up inevitable parallels with the present: previously ambivalent people had to take sides. De Beauvoir and Sartre founded Les Temps modernes, the publication which would be “a laboratory of new ideas and a talent scout rolled into one.” In the first issue, in October 1945, Sartre announced its purpose:

Every writer of bourgeois origin has known the temptation of irresponsibility. I personally hold Flaubert personally responsible for the repression that followed the Commune because he did not write a line to try to stop it. It was not his business, people will perhaps say. Was the Calais trial Voltaire’s business? Was Dreyfus’s condemnation Zola’s business? We at Les Temps modernes do not want to miss a beat on the times we live in. Our intention is to influence the society we live in. Les Temps modernes will take sides.

Existentialism, alongside what would become known as New Journalism, would flourish in the magazine’s pages, and its founders would be catapulted into fame—“Philosopher Sartre. Women Swooned,” read the photo caption of a 1945 Time magazine piece on “the literary lion of Paris who had bounced into Manhattan.” Against the backdrop of the Cold War, Poirier documents the poisoned chalice that stardom was for both Sartre and de Beauvoir (for her, with the added backlash to The Second Sex, both from readers and from resentful peers like Camus and Bellow), along with the assorted fallings out over western intellectuals’ relationship to Soviet communism.

*

Poirier, who grew up in Paris and has worked as a journalist between there and London for the last two decades, compares the research process to “reconstructing a crime scene.” She went a bit gonzo and immersed herself. She booked de Beauvoir’s room; turned off the heat in her apartment for two days; became obsessed with how long the “ghosts” she was “stalking” had to queue for honey or sugar; how they had to mend and reuse their own old clothes.

She tells me of the painstaking revision she went through after having written close to a thousand pages; she actually presented her publisher with 800, with the caveat that those were only half the book. “My first draft was a sort of monster. My introduction was a hundred pages long, a stream of consciousness. It needed to come out [of me,] but it didn’t work at all. I needed to put it on the page—but next time, I won’t impose that on my editor!” she now laughs.

We end our conversation at a coffee shop where she wrote a lot of the book, in the Île St Louis. There are wooden benches, black and white tiles, reading lamps and a view to the back of Nôtre Dame. We pay double digits for mint tea. I leave with a coaster scribbled with her recommendations. I walk away and cross the Seine, and can’t resist standing in one the Pont Louis Philippe’s lone balconies opening to the water. Someone’s left a supermarket bag full of baguettes by the waterside, and some pigeons are discreetly eating the bread. James Salter wasn’t in the city until many years later, but perhaps he captured what Paris—and perhaps any city, when one is in a certain state of mind—felt and feels like better than anyone in his memoir Burning the Days, serving as this book’s epigraph:

Paris was not weary of us. We were still handsome and admired; they smiled and turned on the street. The rooms were chill but they had proportion and there was more than a hint of another life, free of familiar inhibitions, a sacred life, this great museum and pleasure garden evolved for you alone.

Marta Bausells

Marta Bausells is an editor-at-large for Literary Hub. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, Electric Literature, Literary Review and other publications, and she is the creator and former editor of the Guardian Books Network. She lives in London and originally hails from Barcelona. You can find her on Twitter @martabausells.