Lolita: From Transgressive Lit to Pop Iconography

Or How We Ended Up with Lana Del Rey

In the summer of 1948, Vladimir Nabokov started writing Lolita during one of his annual butterfly collecting trips (yes, really). 60 years later, Katy Perry belted the lyric, “I studied Lolita religiously,” in the eponymous song of her second album, One of the Boys, the cover of which features Perry sprawled out on a lawn in a sunhat and retro bikini top—a reference to a scene in Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film adaptation of the novel.

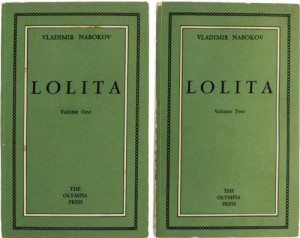

Nabokov finished writing Lolita on December 6th, 1953. After Viking, Simon & Schuster, New Directions, Farrar Straus & Giroux, and Doubleday rejected the manuscript, he resorted to publishing it in Paris with Olympia Press. Upon Lolita’s first publication in 1955, Sunday Express editor John Gordon condemned it as “the filthiest book I have ever read.” Shortly thereafter, Lolita was banned in the United Kingdom and France. Despite lasting controversy, the book was published in New York on August 18th, 1958 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons and in London the year after by Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

Nabokov finished writing Lolita on December 6th, 1953. After Viking, Simon & Schuster, New Directions, Farrar Straus & Giroux, and Doubleday rejected the manuscript, he resorted to publishing it in Paris with Olympia Press. Upon Lolita’s first publication in 1955, Sunday Express editor John Gordon condemned it as “the filthiest book I have ever read.” Shortly thereafter, Lolita was banned in the United Kingdom and France. Despite lasting controversy, the book was published in New York on August 18th, 1958 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons and in London the year after by Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

Since then, the novel has been called everything from “repulsive… highbrow pornography” to the Great American Novel. Some regard it as a story of exploitation, while others see it as a plain old forbidden love story. But how, exactly, did Lolita go from a contested subject to a cultural touchstone? And when did it get reduced to a prototype for relationships between older men and young girls? In commemoration of the anniversary of its U.S. publication, Literary Hub traces the world’s fascination with one of the most challenged books of all time.

Since then, the novel has been called everything from “repulsive… highbrow pornography” to the Great American Novel. Some regard it as a story of exploitation, while others see it as a plain old forbidden love story. But how, exactly, did Lolita go from a contested subject to a cultural touchstone? And when did it get reduced to a prototype for relationships between older men and young girls? In commemoration of the anniversary of its U.S. publication, Literary Hub traces the world’s fascination with one of the most challenged books of all time.

1959: Just a year after Lolita’s U.S. publication, the Italian novelist Umberto Eco wrote a parody of the novel called “Granita,” later published in his 1993 collection Misreadings. In “Granita,” the narrator, Umberto, muses on his secret lust for Granita, an elderly woman. He claims he longs “to catch a closer glimpse of those faces furrowed by volcanic wrinkles, those eyes watering with cataract, the twitching movements of those dry lips sunken in the exquisite depression of a toothless mouth, lips enlivened at times by a glistening trickle of salivary ecstasy.” And they said Lolita was filthy.

1959: Just a year after Lolita’s U.S. publication, the Italian novelist Umberto Eco wrote a parody of the novel called “Granita,” later published in his 1993 collection Misreadings. In “Granita,” the narrator, Umberto, muses on his secret lust for Granita, an elderly woman. He claims he longs “to catch a closer glimpse of those faces furrowed by volcanic wrinkles, those eyes watering with cataract, the twitching movements of those dry lips sunken in the exquisite depression of a toothless mouth, lips enlivened at times by a glistening trickle of salivary ecstasy.” And they said Lolita was filthy.

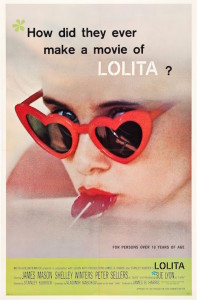

1962: Sue Lyon, 14 at the time of filming, starred as Dolores Haze in the first movie adaptation of Lolita, directed by Stanley Kubrick. Nabokov wrote the screenplay for the film between March and September of 1960, and though he is credited for it, Kubrick and producer James B. Harris ended up rewriting most of Nabokov’s obscenely long script. Censorship laws were in full throttle during the time of production, prohibiting Kubrick from conveying the sexual nature of the relationship between Lolita and Humbert Humbert. Kubrick later said, “I believe I didn’t sufficiently dramatize the erotic aspect of Humbert’s relationship with Lolita. If I could do the film over again, I would have stressed the erotic component of their relationship with the same weight Nabokov did.” Fun fact: Heart-shaped sunglasses, now a pop cultural shorthand for underage sexuality, appear in neither Nabokov’s original work nor the film itself.

1962: Sue Lyon, 14 at the time of filming, starred as Dolores Haze in the first movie adaptation of Lolita, directed by Stanley Kubrick. Nabokov wrote the screenplay for the film between March and September of 1960, and though he is credited for it, Kubrick and producer James B. Harris ended up rewriting most of Nabokov’s obscenely long script. Censorship laws were in full throttle during the time of production, prohibiting Kubrick from conveying the sexual nature of the relationship between Lolita and Humbert Humbert. Kubrick later said, “I believe I didn’t sufficiently dramatize the erotic aspect of Humbert’s relationship with Lolita. If I could do the film over again, I would have stressed the erotic component of their relationship with the same weight Nabokov did.” Fun fact: Heart-shaped sunglasses, now a pop cultural shorthand for underage sexuality, appear in neither Nabokov’s original work nor the film itself.

1966: Russell Trainer published The Lolita Complex, a book that investigated the psychology behind grown men’s sexual attraction to young girls. The Lolita Complex was poorly received and even considered a sham, as Trainer had no credentials whatsoever as a psychologist. On the bright side, it did well in Japan, and the book is widely credited with originating the Japanese term “lolicon.” On the less bright side, lolicon refers to media, mainly manga, that combines the childlike and the erotic.

1966: Russell Trainer published The Lolita Complex, a book that investigated the psychology behind grown men’s sexual attraction to young girls. The Lolita Complex was poorly received and even considered a sham, as Trainer had no credentials whatsoever as a psychologist. On the bright side, it did well in Japan, and the book is widely credited with originating the Japanese term “lolicon.” On the less bright side, lolicon refers to media, mainly manga, that combines the childlike and the erotic.

1979: Woody Allen’s Manhattan hit the big screen, depicting the romance between 42-year-old Isaac Davis (Allen) and 17-year-old Tracy (Mariel Hemingway). When Mary Wilkie (Diane Keaton) learns of the relationship, she says, “Somewhere Nabokov is smiling.” Some have speculated that Manhattan was inspired by Lolita.

1979: Woody Allen’s Manhattan hit the big screen, depicting the romance between 42-year-old Isaac Davis (Allen) and 17-year-old Tracy (Mariel Hemingway). When Mary Wilkie (Diane Keaton) learns of the relationship, she says, “Somewhere Nabokov is smiling.” Some have speculated that Manhattan was inspired by Lolita.

1980: The Police released the hit single “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” about a lustful, tormented relationship between a schoolgirl and her teacher. In case you don’t pick up on the song’s, er, subtle themes, Sting makes sure you get the picture with the line, “He starts to shake and cough/Just like the old man in/That book by Nabokov.” Sting originally cited his early teaching experience as the inspiration for the song: “I wanted to write a song about sexuality in the classroom. I’d done teaching practice at secondary schools and been through the business of having 15-year-old girls fancying me—and me really fancying them! How I kept my hands off them I don’t know.” Somehow, the song managed to take on even creepier undertones in 2001, when Sting said, “You have to remember we were blond bombshells at the time and most of our fans were young girls so I started role playing a bit. Let’s exploit that.” Sounds like a page out of Humbert’s book, alright.

1980: The Police released the hit single “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” about a lustful, tormented relationship between a schoolgirl and her teacher. In case you don’t pick up on the song’s, er, subtle themes, Sting makes sure you get the picture with the line, “He starts to shake and cough/Just like the old man in/That book by Nabokov.” Sting originally cited his early teaching experience as the inspiration for the song: “I wanted to write a song about sexuality in the classroom. I’d done teaching practice at secondary schools and been through the business of having 15-year-old girls fancying me—and me really fancying them! How I kept my hands off them I don’t know.” Somehow, the song managed to take on even creepier undertones in 2001, when Sting said, “You have to remember we were blond bombshells at the time and most of our fans were young girls so I started role playing a bit. Let’s exploit that.” Sounds like a page out of Humbert’s book, alright.

1992: Frustrated with Nabokov for giving Lolita “no voice,” Kim Morrissey took matters into her own hands and published Poems for Men who Dream of Lolita. The poems are written from Dolores’s perspective as she reflects on the events of the novel and read like sparkly, soul-baring diary entries.

1992: Frustrated with Nabokov for giving Lolita “no voice,” Kim Morrissey took matters into her own hands and published Poems for Men who Dream of Lolita. The poems are written from Dolores’s perspective as she reflects on the events of the novel and read like sparkly, soul-baring diary entries.

1995: Italian writer Pia Pera published Diario di Lo, or Lo’s Diary, a novel that retells the story from Lolita’s point of view. The book may be similar to Morrissey’s in concept, but the execution is vastly different. Pera depicts Dolores as a cruel sadist and Humbert as physically unattractive. Diaro di Lo was largely disparaged. Richard Corliss wrote, “There are only two reasons for such a book: gossip and style,” while Entertainment Weekly said it “drags down Nabokov’s blackly satiric vision, set in atomic-age suburban America, to the level of a 1990s teen sex comedy.”

1995: Italian writer Pia Pera published Diario di Lo, or Lo’s Diary, a novel that retells the story from Lolita’s point of view. The book may be similar to Morrissey’s in concept, but the execution is vastly different. Pera depicts Dolores as a cruel sadist and Humbert as physically unattractive. Diaro di Lo was largely disparaged. Richard Corliss wrote, “There are only two reasons for such a book: gossip and style,” while Entertainment Weekly said it “drags down Nabokov’s blackly satiric vision, set in atomic-age suburban America, to the level of a 1990s teen sex comedy.”

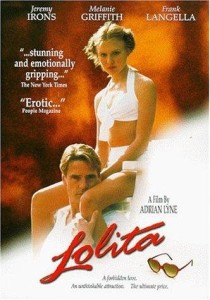

1997: It’s not an American literary classic until it’s been made into a movie at least twice, so when Adrian Lyne directed a second screen adaptation of Lolita, he secured its place in the canon. The movie stars Jeremy Irons as Humbert and Dominique Swain, who was 15 during filming, as Dolores. The film received mixed reviews. James Berardinelli wrote, “Lolita is not a sex film; it’s about characters, relationships, and the consequences of imprudent actions,” while Keith Phillips wrote, “Lyne doesn’t seem to get the novel, failing to incorporate any of Nabokov’s black comedy—which is to say, Lolita’s heart and soul.”

1997: It’s not an American literary classic until it’s been made into a movie at least twice, so when Adrian Lyne directed a second screen adaptation of Lolita, he secured its place in the canon. The movie stars Jeremy Irons as Humbert and Dominique Swain, who was 15 during filming, as Dolores. The film received mixed reviews. James Berardinelli wrote, “Lolita is not a sex film; it’s about characters, relationships, and the consequences of imprudent actions,” while Keith Phillips wrote, “Lyne doesn’t seem to get the novel, failing to incorporate any of Nabokov’s black comedy—which is to say, Lolita’s heart and soul.”

2003: Reading Lolita in Tehran is Iranian author Azar Nafisi’s memoir about her time teaching at the University of Tehran during the revolution and her life during the Iran-Iraq War. Accounts of these events are interspersed with stories about the formation of Nafisi’s book club, which consisted of female students who met with Nafisi weekly to discuss works of Western literature, including Lolita. In the book, Nafisi compares the Iranian regime to Humbert’s projection of his own ideals onto Lolita. She writes that the government imposes its “dream upon our reality, turning us into figments of his imagination.”

2003: Reading Lolita in Tehran is Iranian author Azar Nafisi’s memoir about her time teaching at the University of Tehran during the revolution and her life during the Iran-Iraq War. Accounts of these events are interspersed with stories about the formation of Nafisi’s book club, which consisted of female students who met with Nafisi weekly to discuss works of Western literature, including Lolita. In the book, Nafisi compares the Iranian regime to Humbert’s projection of his own ideals onto Lolita. She writes that the government imposes its “dream upon our reality, turning us into figments of his imagination.”

2012: Lana Del Rey’s second album, Born to Die, is essentially a lyrical shrine to Lolita. The first track, “Off to the Races” includes the novel’s famous first line, verbatim, and “Carmen” is a nod to a pop song Dolores sings. Lana alludes to the Kubrick version in “Diet Mountain Dew” when she sings, “Baby, put on heart-shaped sunglasses/’Cause we’re gonna take a ride.” It seems more than fair to hold Lana responsible for the recent preponderance of heart-shaped sunglasses at Coachella and the slew of Nabokov misquotes on Tumblr. And in case you were still wondering about her literary preferences, the bonus version of Born to Die features a song called “Lolita.”

2012: Lana Del Rey’s second album, Born to Die, is essentially a lyrical shrine to Lolita. The first track, “Off to the Races” includes the novel’s famous first line, verbatim, and “Carmen” is a nod to a pop song Dolores sings. Lana alludes to the Kubrick version in “Diet Mountain Dew” when she sings, “Baby, put on heart-shaped sunglasses/’Cause we’re gonna take a ride.” It seems more than fair to hold Lana responsible for the recent preponderance of heart-shaped sunglasses at Coachella and the slew of Nabokov misquotes on Tumblr. And in case you were still wondering about her literary preferences, the bonus version of Born to Die features a song called “Lolita.”

Rebecca Brill

Rebecca Brill is a writer who lives and studies in Minneapolis. Her work has appeared in The Paris Review Daily, Broadly, Lilith, and elsewhere.