Living in the Shadow of Your Father’s Iconic Song

Sarah Curtis: “Maybe we’ve just learned what my teenage daughter does not yet fully know: that to be held to a law is often to be loved.”

From: music@sonnycurtis.com

Sent: Monday, August 17, 2015 4:47 PM

Subject: Re: Two quick “I Fought the Law” questions

Hi Randal,

Thank you for your interest in “I Fought the Law.” To answer your questions:

1) There was nothing other than my imagination that inspired me. I was alone in my living room one afternoon with a West Texas sandstorm going on outside, trying to write a song. I was just pickin’ my guitar and letting my mind go, the way you do when you write a song. It only took about twenty minutes. It sort of scares me, but I don’t think I ever wrote it down. I just carried it in my head ‘til we needed it. But it’s one of my best copyrights and I’ve always been grateful that the Rock and Roll gods came through for me and helped me make it happen.

2) I had no idea what a protest song was at the time and certainly didn’t know what punk rock was. Genres like psychedelic, punk, grunge, heavy metal, etc., didn’t come along until years later.

I was really trying to write a country song, but when we recorded the album, In Style with the Crickets, I transcribed it to a rock ‘n’ roll song and there ye are. It has always amused me that people try to analyze it. I don’t mean to sound flippant, but I’ve never taken it that seriously. To me, it’s one of my songs that I’m real proud of. I’m just thankful that it stirs something in people and makes them like it, for whatever reason. I hope they, and you, continue to do so.

Thank you for your interest and support.

Very truly yours,

Sonny Curtis

*

It’s a mystery even to my father, how a brainstorm at age twenty-two would go on to define much of his life—and mine. It’s certainly not the best song he ever wrote. Yet Rolling Stone magazine ranks it at #175 on the list of 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. It’s as if the reaction to the song has eclipsed the song itself, which is more than the sum of its simplistic parts. A three-chord melody, lyrics a child could write: I needed money, and I had none. I fought the law, and the law won. Anarchy at its most elemental.

Maybe “I Fought the Law” came not from a place of anarchy but from a place of yearning, a desire for the stars to better align, for the laws of the universe to make sense.

Perhaps the song’s simplicity is its strength, the thing allowing it to serve so many agendas. It is what music publishers call an “evergreen” song, and indeed, it has resurfaced at least once a decade since The Bobby Fuller Four released it in 1965. In the 1970s, the Dead Kennedys released a punk parody of it as a social commentary after courts acquitted the man who assassinated San Francisco mayor George Moscone and his supervisor, politician and gay rights activist Harvey Milk. In 1989, US troops blasted The Clash’s version outside Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega’s compound until he gave himself up—one more person done in by rock ‘n’ roll. In 2004, the song was used as a marketing tool when Green Day covered it for a Pepsi/iTunes Super Bowl ad. Recently I opened my mailbox to find my father had sent me a larger birthday check than usual. When I called to thank him, he said, “Well, don’t get too used to it, honey. ‘I Fought the Law’ had a good year in Australia.”

To grow up surrounded by the physical manifestations of a parent’s art is a complicated dynamic, especially when that art enters the public sphere. If my father were a psychiatrist or a car dealer, I wouldn’t be confronted with his work while strolling the cheese aisle at my local Kroger. My father’s songs pierce my reality—and that’s often what it feels like, a puncture, a breach—at strange and unexpected times: when I’m riding an elevator, or watching TV, or, as “I Fought the Law” did the other day, while wandering a vintage car show with my kids. While not unwelcome, these moments can feel lonesome. I would never announce to strangers in my vicinity, “My dad wrote this song!” Instead I inhabit a three-minute pocket of solitude, everyone around me oblivious to my father’s words pulsing through my head, dredging up a lifetime of memories and associations and sensations that are mine and mine alone.

As a teenager I learned the song’s currency, its cool factor, how when people (boys especially, it seemed) discovered my connection to it, they treated me a little nicer. I’ve used the song to my advantage a lot in life, even if only in my head. How many times have I hung on to it like my childhood security blanket when things were falling apart around me? These people suck/That woman is rude/I’m no good at this job…but my dad wrote “I Fought the Law.”

It’s hard not to wonder about the provenance of a song that has played such a significant role in my psyche. Fellini said the pearl is the oyster’s autobiography. So at the risk of amusing my father, I, too, wonder what irritants combined to form his most famous pearl?

He wrote the song in the summer of 1959, five months after his friend Buddy Holly’s tragic death in a plane crash. He’d been bouncing around the country chasing gigs from coast to coast, but that summer he was crashing at a friend’s house in Slaton, Texas, while playing lead guitar for the Crickets, Buddy’s former back-up band. The Crickets hired my dad to replace Buddy on lead guitar after the singer’s death. But with Buddy gone, their gigs were growing thin.

The details are well-known, but they bear repeating. On February 2, 1959, Buddy played his final show at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake Iowa. It was a routine stop on “the tour from hell,” as he and his tour mates had nicknamed it. Their bus’s heating system broke down and Buddy’s drummer was hospitalized for frostbite. Several musicians caught the flu, including J.P. Richardson, known as The Big Bopper. A drafty bus, a frigid night, a mean stretch of highway, a flu virus spreading fast. Buddy decided to charter a plane to their next gig in Minneapolis. It wasn’t a tough choice, I’m sure. What was fame for if you couldn’t pull a few strings occasionally? Not only was he cold and tired, he had a suitcase full of dirty clothes. He wanted to reach their next destination a day early to catch up on sleep and laundry. Instead, just after midnight, the plane fell from the sky and careened into a desolate stretch of Iowa cornfield.

Sitting on his friend’s couch that day in July of 1959, my father let his mind wander as he looked out the window at the all-too familiar West Texas scenery: brown grass, flat road, dirty sky. The song came to him quickly, a twenty-minute brainstorm in a sandstorm. I’ve sometimes wondered if writing “I Fought the Law” was a subconscious attempt for him to impose order onto a chaotic world. First it was a Dust Bowl world, where the ground and sky could switch places. And later, it was a world where a teenage friend could shoot to international stardom, then fall from the sky. Maybe “I Fought the Law” came not from a place of anarchy but from a place of yearning, a desire for the stars to better align, for the laws of the universe to make sense.

My father was born into a world buckled under the weight of law. When he was five, his family cultivated enough cotton to move off their farm and into a small house in the nearby town of Meadow. It was around this time that the family began attending the Church of Christ. Before the move to Meadow, they’d had been too mired in farming to worry about religion, their bible the almanac. And of course the cycles of farming provided their own doctrine, from harrow to harvest to harrow again, the jobs at the mercy of the season, the season at the mercy of the sky, the sky at the mercy of a law too powerful to comprehend. That’s what church was for.

My dad has clear memories of the sweltering hot summer revival meetings, how the only relief came from the little handheld fans printed with pictures of Jesus and Mary that the church ladies passed out. In a brief memoir he gave me, he wrote:

Brother Shannon and the other “country clergy” would shout and holler from the pulpit and remind you constantly that if you didn’t get saved and walk the straight and narrow, you would burn in hell. Not just to the ground, once and for all. Hell no! Forever on out, eternity. As I grew older and was able to grasp the meaning of things, those dour teachings scared the hell out of me. I thought often about what it would be like to just keep on burning with no end in sight.

I can’t fully fathom this nightmare, having myself grown up in Protestant churches where hymns were warbled apathetically and Hell was an abstraction. But Hell was real in Meadow, Texas, and nobody escaped those fiery sermons unscathed.

The Church of Christ also forbade musical instruments from being played during service; only a cappella music was (and often still is) allowed. It was a hard law for my young father to understand. In his memoir, he reflects on a revival meeting he attended around age ten, led by a fire-and-brimstone pastor aptly named Brother Loveless. To lead the singing, the church brought in a song leader from a nearby congregation in a neighboring town. When the song leader approached the choir, he reached into his breast pocket and pulled out a tuning fork to set the key. After the song ended, Brother Loveless resumed the pulpit. What you just witnessed was a man using an instrument of the devil! he hollered. It wasn’t a revival meeting without a hot blast of damnation, yet this one especially lodged in my father’s brain. As he wrote in his memoir, “By the time he was finished, he had dragged that song leader right up to the gates of hell where he was ready to happily shove him through.” The sermon split the church down the middle. The adults sent the kids outside after the service to discuss the situation. When the meeting adjourned, Brother Loveless was gone and the song leader stayed, but just barely.

In his memoir, The Prince of Frogtown, Rick Bragg writes about his own father’s similar fire-and-brimstone religion around the 1940’s that held their Appalachian cotton mill town in its grip. “They were still a new denomination then, but had spread rapidly in the last fifty years around a nation of exploited factory workers, coal miners, and rural and inner-city poor…Biblical scholars turned their noses up, calling it hysteria, theatrics, a faith of the illiterate. But in a place where machines ate people alive, faith had to pour even hotter than blood.”

Even hotter than blood. The laws of the flesh were necessary in these impoverished, agricultural communities, even if people could never live up to them, even if, as Bragg writes, “the preacher laid down a list of sins so complete it left a person no place to go but down.” The church tethered the townspeople to a greater cause, which kept them plowing in the face of drought, faithful in the face of boredom, and sober in the face of hopelessness. It’s no wonder they came to rely upon the laws, the preacher’s voice cleansing their mean and bitter thoughts like fire cleanses refuse from a field, allowing sunlight to penetrate the soil.

My father would say I’m overthinking all of this. When asked about the song’s origins, he focuses on the creative process—“pickin’ my guitar and letting my mind go”—rather than on the lyrics. I think it embarrasses him that people have assumed he’s an anarchist or ex-con. But think about it: my father needed money so he turned to art, writing a song about a guy who needed money so he turned to armed robbery. Both men longed for freedom; one from prison, the other from poverty, religion, and unending rows of cotton.

Now that I am the lawmaker for three children of my own, I find myself wistful for the days when others made the rules for me.

For my father, all those freedoms hinged on a freedom of mind (and in that sense, he was an anarchist, just as every artist is). Since he wrote his first song at age fourteen from the seat of his father’s tractor, songwriting had been his exit valve, a way to escape the facts on the ground. And just as he had that day, he felt the old rush of blood, the transformation from chaos to cosmos. The sand crackling against the screen door became a high-hat drum. A nearby tractor drove a baseline through his gut. It was almost a rumble but not quite a song, not yet, but wait—breaking rocks, hot sun. The world transcribed into music.

*

We take the law for granted when we are young. We aim, as my father did that hot July day, in the direction of freedom, shaking off the bonds of family and place to form shiny identities. Now that I am the lawmaker for three children of my own, I find myself wistful for the days when others made the rules for me. Watch your tone with me, put your napkin on your lap, off to bed you go. There was comfort in those laws, in knowing people were watching out for me, conditioning me for this world. Not that I appreciated the laws when I was young, always ducking the rules, my teenage years a string of gleeful infractions. Now I see my teenage daughters weaving their way around the same obstacle course, their lives like a corn maze. They can stray off course a bit, but there will always be someone nearby to guide them back on path, as there was for me.

My father never bothered with enforcing household rules; he left that to my mother. Instead, he laid down his law in the form of lectures: on nutrition, history, personal finances, car maintenance, chord structures, on and on, without giving any thought to age appropriateness. He lectured me on interest rates when I was seven and bathtub safety when I was seventeen. His sermons were less apocalyptic than the country clergy of his youth, but perhaps he learned a thing or two in those humid tents, for once he started, it was hard to shut him down. His lecturing caused a rift with my mother, especially as I grew older and started leaving the dinner table early because I couldn’t listen to him anymore. “Why can’t you just talk to her like a normal kid?” I’d hear her gripe as I ascended the stairs to my bedroom.

Today my father’s lectures are swept from my mind, though I can still make out the bleached ruins of a few: a rough chronology of the U.S. presidents, an argument against the Capital Gains Tax, Tippecanoe and Tyler Too. If my father was the law in my life, I didn’t fight it so much as ignore it.

I wish I had known how to listen to him, and I wish he had known how to talk to me like a normal kid. But that is not how he was raised. And so, over the years, we’ve learned better how to abide by each other’s laws. Or maybe we’ve just learned what my teenage daughter does not yet fully know: that to be held to a law is often to be loved.

My father still lectures me, though less than he once did. Today he prefaces his laws with apology: “Far be it for me to give you parenting advice…” and I comply. Thanks, Dad. I’ll remember that. What’s the point of arguing? The future surges toward us in unrelenting waves, splitting the stars, eroding the earth. Today my dad is eighty-eight, an old man facing down the ultimate law. Sure, that law will win one day, as it will for all of us.

But without it, what would we fight against?

__________________________________

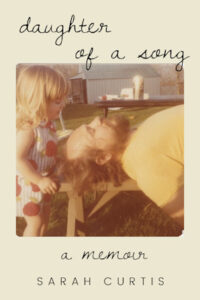

From Daughter of a Song by Sarah Curtis. Copyright © 2025. Available from Texas Tech University Press.

Sarah Curtis

Sarah Curtis’s debut memoir Daughter of a Song is forthcoming in fall 2025 by the Texas Tech University Press. It is the winner of the Lou Halsell Rodenberger Prize, awarded to a manuscript illuminating women’s roles in the history, culture, and letters of Texas and the American West. Her essays have appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Threepenny Review, Creative Nonfiction, Salon, The Colorado Review, the Huffington Post, and elsewhere. In addition, her work has been noted in the Best American Essays series and anthologized in River Teeth: Twenty Years of Creative Nonfiction. A native Southerner, Sarah lives in Michigan. More of her writing can be found at sarahcurtiswriter.com.