Little Cash, Lots of Censorship: Bothayna Al-Essa on Opening a Bookstore in Kuwait

“I wonder how much of a dreamer I was, and why—at the time—I didn’t see myself as a dreamer.”

Translated from the Arabic by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain.

On March 10, 2016, I became a bookseller.

I was on a quest to bring back a lost form of bookstore. The kind that offers a creative space for exchanging ideas and an enduring, steadfast haven. A diametric contrast to all things seasonal and ephemeral, to second-rate books flaunted on bestseller shelves, and to the transient hubbub of book fairs. I wanted it to be a place that could make its mark on people’s lives, bridging the divide between cultural and community work.

It was to be a small bookstore, trying to revive traditions that disappeared when bookstores turned into megastores selling tablets, cell phones, cigarettes (here in Kuwait, anyway), water bottles, and candy. A small bookstore tucked into a corner of a mall, specializing in literature, thought, and philosophy.

Takween was established with a budget so flimsy it was laughable, and with no feasibility study to support it—it was built on instinct alone. I chose the location and my team and I began the process of equipping it.

I wanted it to be a place that could make its mark on people’s lives, bridging the divide between cultural and community work.

Set-up costs—for bookshelves, furniture, the accounting system, computers, and cash registers—ate up so much of our cash that we allocated a mere one thousand Kuwaiti dinars for buying books. And with the naivety of the uninitiated, and a total lack of experience, we went to the Kuwait International Book Fair in 2015 to buy books directly from the publishers, at a discount sometimes as low as twenty percent.

On top of that, with the idealism of dreamy readers and paying no attention to market demands, we favored the classics we loved. Books we’d read many years earlier that we still talked about at every meeting as if we owed them an eternal debt. Of these are Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and a handful of Mario Vargas Llosa’s, Isabel Allende’s, and Eduardo Galeano’s works. Books by Jorge Luis Borges and a few copies of Sophie’s World were also on our list. We were expressing our gratitude to the authors who’d had the deepest impact on our innermost selves.

Later, when we began to arrange the books on the shelves, we were alarmed by the size of the gaps that remained. Our bookshelves were so bare that when another bookstore owner came to congratulate us—and perhaps to check out how serious we were as new competitors—he commented that it wasn’t a bookstore as much as it was a diwaniya. And he was right: it was more like those rooms in Kuwaiti homes where guests gather to socialize and discuss every topic under the sun.

Our problem was a matter of financing, but the solution had nothing to do with finances. I’d begun to sense that publishers were uneasy about dealing with these eager but unknown young people wanting to buy books in bulk with no budget—and for a bookstore no one had heard of—so I put on my author’s hat and began to reach out to my contacts.

My publisher in Beirut, Arab Scientific Publishers, didn’t object to sending over a shipment of books to fill the bookstore. And Hassan Yaghy, iconic publisher and director of Dar Al-Tanweer, replied to my email saying he was close to my uncles and that he could send even more books than the ones I’d requested, adding, with a kindness that brought tears to my eyes, “You can pay in six months, or in a year, or not at all.”

I asked my author friends to help open channels with other publishers. Novelist Haji Jaber was my ticket to the Arab Cultural Center, and Mohammed Hasan Alwan lobbied his venerable publisher, Dar Al-Saqi, to make his books available in Takween, despite the near-exclusivity contracts in place with other bookstores.

Suddenly, a huge shipment of books, containing hundreds of titles and thousands of copies, was on its way to me in Kuwait. And once again, our naivety and lack of experience meant that it hadn’t crossed our minds to acquire an import-export license, and we had no idea that getting a shipment of books out of customs was like having a tooth pulled with no anesthetic. Nor did we know that we needed to have the relevant permits from the Ministry of Information for the books to be allowed into Kuwait.

The Ministry of Information staff at the airport customs department were exceptionally cooperative. I think their enthusiasm for the birth of a cultural project, and especially one delivered by Kuwaiti hands, is what gave me the flexibility, in the beginning, to get the books into Takween and avert the utter scandal of opening a bookstore with no books.

After the first flush of opening faded, however, I found myself in an almost daily confrontation with censorship. Because we had no liquidity, we were running the project ourselves, with no staff and no salaries.

It wasn’t a commercial project, it was a romanticized journey of self-destruction, which I survived for reasons I don’t completely understand.

That year was brutal, and ridiculously so. When I look back on those days, I wonder how much of a dreamer I was, and why—at the time—I didn’t see myself as a dreamer but as a pragmatic manager trying to make a go of the project without having any commercial ambitions, backup plans, or experience, and doing it solely for the love of books.

Part of me—the curious part, to be specific—wanted to do everything myself: going over invoices, handling correspondence, issuing stock requests, printing barcodes, dusting, putting books on shelves and advertising them. My tasks included, of course, following up on our permits with the Ministry of Information and receiving new lists of banned books that I wasn’t supposed to have in my possession, let alone sell.

In other words, it wasn’t a commercial project, it was a romanticized journey of self-destruction, which I survived for reasons I don’t completely understand. I was alone in the wilderness, with nothing to cover my back, exposed to prosecution and fines and facing the ogre of censorship with its thousands of arms. And in the grim world of capitalism, it was a struggle to convince anyone to invest in a book instead of buying a caffè mocha with cream or getting a Botox shot.

That year, I felt I was being slapped in the face time and again as I saw books that had been approved in previous years being banned. One Hundred Years of Solitude, which I’d bought from the bookfair in the nineties, was apparently now not allowed. The Arab Cultural Center’s Arabic edition of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four was approved, while Dar Al-Tanweer’s edition was not. The banning of Ghassan Kanafani’s timeless novel, Men in the Sun, was particularly painful. And Nikos Kazantzakis’ Zorba the Greek was banned and approved, then banned and approved again several times in one year. When one of Abdul Rahman Munif’s novels was called in for inspection, I asked the censor for an explanation, since the novel had been approved and in circulation for years. She said the author might have changed something between editions—as if Munif having been dead for twelve years was of no consequence!

The system was arbitrary and irrational, a bureaucracy with neither head nor tail, like a poem by Baudelaire. I’ve always wondered whether some hidden genius lay behind its effectiveness, or whether it was the complete lack of such genius that propelled it.

Over the past ten years, it has become clear to me how many of our freedoms have been curtailed. What the censor used to approve in the nineties is banned today. The state has rolled back decades of progress while society—with the help of the latest platforms and technology—has gained access to content so vast it’s impossible to censor. It’s our exclusively homegrown version of Alice’s Wonderland, absurd and devoid of logic. The only difference is that it’s far from what any of us would call fun.

__________________________________

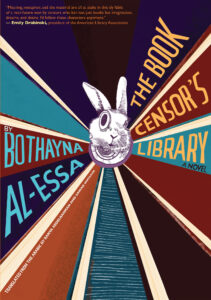

The Book Censor’s Library by Bothayna Al-Essa, translated from the Arabic by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain, will be published by Restless Books on April 30, 2024.

Bothayna Al-Essa

Bothayna Al-Essa is the bestselling Kuwaiti author of nearly a dozen novels and additional children’s books. She is also the founder of Takween, a bookshop and publisher of critically acclaimed works. Her most recent book, The Book Censor’s Library, won the Sharjah Award for Creativity in the novel category in 2021 and is her third novel to appear in English, after Lost in Mecca and All That I Want to Forget. Al-Essa was author-in-residence at the British Centre for Literary Translation for the summer of 2023, and the recipient of Kuwait’s Nation Encouragement Award for her fiction in 2003 and 2012. She has written books on writing and led writing workshops throughout the Arab world.