Lit Hub’s Most Anticipated Books of 2026

314 Books To Read in the New Year

MARCH

***

Helen Garner, Stories

Helen Garner, Stories

Pantheon, March 3

Garner is an Australian laureate, known for capturing the 1970s demi-monde and the minefield of intimate social relationships. I fell for the coolly riveting The Spare Room a few years back and keep returning to the well. In this new collection of short fiction, we can expect the same frank humor and exquisite detail spread across a pantheon of spiky characters. Hometown gossips and lonely girls to the front. –BA

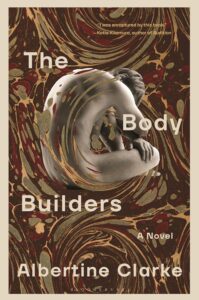

Albertine Clarke, The Body Builders

Albertine Clarke, The Body Builders

Bloomsbury, March 3

Is speculative surrealism a thing? If it’s not, I’m making it one to write about why I’m looking forward to The Body Builders. I like reading about isolation and what it does to a person’s sense of self, and what it means to exist between your mind and the physical world. It feels so lonely, but also fantastical. Definitely my kind of niche. –OS

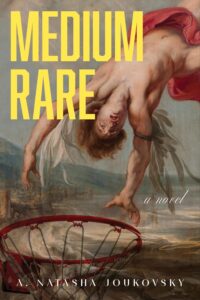

A. Natasha Joukovsky, Medium Rare

A. Natasha Joukovsky, Medium Rare

Melville House, March 3

I loved Joukovsky’s witty romp The Portrait of a Mirror, and I have to say the premise of her latest sounds perfectly absurd: a mid-level Washington lobbyist fills out a perfect March Madness bracket and faces “spiraling consequences”! It’s a retelling of the Icarus story narrated by an actual Cassandra! I’m going to need some fun in March, and I’m counting on this book to bring it to me. –ET

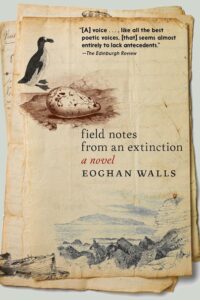

Eoghan Walls, Field Notes from an Extinction

Eoghan Walls, Field Notes from an Extinction

Seven Stories, March 3

Here’s more fodder for the semi-annual call for more poet novels: Northern Irish poet Eoghan Walls’ sophomore novel is narrated via a nineteenth-century ornithologist’s notebook as he lives on a remote Irish island. Ignatius Green, “single-minded and self-righteous, brilliant and bumbling,” must contend with hunger, suspicious locals, and a feral child. A darkly funny literary thriller about research, seabirds, and the terror of parenthood? Absolutely sold. –JG

Jordy Rosenberg, Night Night Fawn

Jordy Rosenberg, Night Night Fawn

One World, March 3

I love when a book has the word “deranged” in the description. That’s how I know a book is for me. Barbara Rosenberg is high on opioids and dying of a terminal illness and, most importantly, writing her memoir. She’s led a complicated life, but she would prefer to write about her thoughts on gender and Karl Marx. Most of all, she wants to write about her relationship with her estranged trans son and her former best friend. But as her condition worsens and her delusions begin to take over, she’s forced to confront these two in a way she never expected. Night Night Fawn sounds smart and funny and messy in equal measure. –MC

Jan Saenz, 200 Monas

Jan Saenz, 200 Monas

Little, Brown, March 3

I’m a simple man. If you pitch me a book premised on the existence of a made-up illegal drug, I’m intrigued. If the plot promises to be a Coen brothers-esque crime comedy about an unprepared college senior thrust into the role of inept street dealer, I’m interested. If the motivating factor behind the drug dealing is a sort of reverse Brewster’s Millions “sell all these drugs in 48 hours or we’ll kill you”, I am going to pre-order the book. –CK

Ariel Dorfman, Konfidenz

Ariel Dorfman, Konfidenz

Other Press, March 3

Ariel Dorfman has spent a career examining the pain of exile and the horrors of dictatorship in books, plays, and essays, and his latest novel zooms in on the personal and internal stresses of suspicion and mistrust. Told mostly through dialogue, Konfidenz is an intensely psychological tete-a-tete about a woman who receives a phone call from a stranger claiming to be her friend, but soon is revealed to have intimate and dangerous knowledge about her life. Dorfman’s own life was upended after the 1973 coup against Salvador Allende, and he draws on his experiences of displacement in this new novel of paranoia and manipulation. –JF

Vigdis Hjorth, tr. Charlotte Barslund, Repetition

Vigdis Hjorth, tr. Charlotte Barslund, Repetition

Verso, March 3

This slim new translation from Verso is classic Hjorth: a deceptively simple family story unfolds into dark and painful corners. Repetition begins with a novelist experiencing a Proustian moment at the opera when she sits next to a teenage girl and her parents. The evident tension between the family of strangers sends the novelist back to memories of being 16 years old, a year of firsts for her. Her world is also enclosed by her parents: her mom anxiously and judgmentally surveils her, while her dad rarely intervenes from his perch of silent authority. Told in direct in introspective prose, Hjorth is able to conjure the creaky overconfidence of adolescence and all its uncertainties. It’s a great book. –JF

Álvaro Enrigue, tr. Natasha Wimmer, Now I Surrender

Álvaro Enrigue, tr. Natasha Wimmer, Now I Surrender

Riverhead, March 3

Álvaro Enrigue is a contemporary master of historical fiction and his new book continues his complex explorations of colonialism in the Americas. Billed as an “alt-Western,” Now I Surrender moves north and forward in time from his previous You Dreamed of Empires to the 1830s in the contested land that is now the US-Mexico border. A young woman is kidnapped by Apaches amidst the tribe’s attempt to endure amid the fighting between the U.S. and Mexico that is engulfing their homeland. The book shifts narratively to Geronimo’s anti-imperial resistance a decade later, as well as to a contemporary family’s trip through the area nearly a century later. The title comes from Geronimo’s surrender to U.S. forces, and the book is full of this sense of opposition and loss: of territory, life, and the possibility of a different future. –JF

Benjamin Hale, Cave Mountain: A Disappearance and a Reckoning in the Ozarks

Benjamin Hale, Cave Mountain: A Disappearance and a Reckoning in the Ozarks

Harper, March 3

Benjamin Hale’s cousin, six-year-old Haley, got lost on a mountain trail at the top of Cave Mountain in the Arkansas Ozarks in 2001. After the largest search and rescue mission in the state’s history, Haley was found, but she had a curious account of an “imaginary friend” she met while lost in the woods. Hale connects that story to another tale that took place in the same wilderness twenty years earlier—a story of a cult, brainwashing, teenage prophets, and murder. –EF

Tanya Bush, Will This Make You Happy: Stories & Recipes from a Year of Baking

Tanya Bush, Will This Make You Happy: Stories & Recipes from a Year of Baking

Chronicle Books, March 3

Before co-founding Cake Zine magazine and becoming the pastry chef at Little Egg, Tanya Bush was a woman in her early twenties without a job, stuck in a sparkless long-term relationship, who had baked a very poor cake. But the process of baking brought her back to something joyful. This culinary memoir, filled with recipes, follows a year of Bush’s life as she learns what it means to be an adult, a baker, and most importantly, happy. –EF

Anand Gopal, Days of Love and Rage: A Story of Ordinary People Forging a Revolution

Anand Gopal, Days of Love and Rage: A Story of Ordinary People Forging a Revolution

Simon & Schuster, March 3

In which Pulitzer and National Book Award finalist Anand Gopal brings us an intimate account of six Syrians on the frontlines of the 2011 revolution. This is Gopal’s bread and butter, so it’s sure to be brilliant, and no topic could be more timely. –ET

Camonghne Felix, Let the Poets Govern: A Declaration of Freedom

Camonghne Felix, Let the Poets Govern: A Declaration of Freedom

One World, March 3

With political hopelessness at its peak, there’s no better time to read Camonghne Felix, a poet who has also worked extensively as a political strategist, and speechwriter. Felix’s memoir-manifesto draws on Black radical poetic traditions to argue for the pragmatic power of poetry, and for language as a tool for liberation. I can’t think of any writer more equipped to call us to action. –JG

Deborah Baker, Charlottesville: An American Story

Deborah Baker, Charlottesville: An American Story

Graywolf, March 3

Future historians will have plenty of awful moments to label as “turning points” in the collapse of the American republic (not to be too pessimistic here), but 2017’s white nationalist take over of Charlottesville, Virginia is definitely in the running for “major” status (recall Trump’s “good people on both sides” reveal, and Biden’s decision to run for president). And as Deborah Baker’s detailed account reveals, the inability of government officials to recognize the Nazi threat would both echo past failures in this country’s capacity to handle extremism, and forecast its refusal to even try. Riveting and important reading. –JD

Terry Tempest Williams, The Glorians: Visitations from the Holy Ordinary

Terry Tempest Williams, The Glorians: Visitations from the Holy Ordinary

Grove Press, March 3

There’s nobody I trust more than Terry Tempest Williams to be able to braid the ordinary with the holy, the divine with the mundane. She’s someone who I’ve always been able to look to, in the need of regaining a faith in the world, a trust in it. Thankfully, at just the right time, The Glorians is coming out this year. A return to the basics that Williams relies much of her thinking upon: “The Glorians” are the small moments, or beings, of majesty, that make up the larger, woven, glittering web of our existence. It can be a coyote running across the desert. A new green growth emerging through a crack in stone. Williams points to these small moments, and poignant visions, as the representations of our hope, our resilience, our bright and gleaming futures. I know I need that now, more than ever. –JH

Simon Morrison, A Kingdom and a Village: A One-Thousand-Year History of Moscow

Simon Morrison, A Kingdom and a Village: A One-Thousand-Year History of Moscow

Knopf, March 3

If Paris is the city of lights, and Rome is the eternal city, what then is Moscow, a massive near 1,000-year-old conurbation in the world’s largest country? Is it still just a “big village” (as it was dismissed by the cosmopolitan citizens of St. Petersburg) founded as a river fortress by merchants, or is it the megacity at the heart of a would-be superpower? Or is it both? These are among the many questions posed by Simon Morrison’s sprawling biography of place, which seeks to understand a nation through the life of its largest city, tracing Moscow’s evolution via dozens of historical upheavals, from war, famine, drought, and much, much more. –JD

M.L. Stedman, A Far-Flung Life

M.L. Stedman, A Far-Flung Life

Scribner, March 3

It’s been almost 15 years since M. L. Stedman’s runaway hit, The Light Between Oceans: her many fans have been patiently awaiting, and are soon to be appeased by a new, masterful epic. A Far-Flung Life is set in the Australian outback, on a plot of land that one family, the McBrides, has held for centuries. In this place that they have loved for generations, a cataclysmic tragedy occurs: it happens, and then it happens again, and again, in the reverberations that utter, soul-searing grief can wreak upon a life. The book asks big questions, and promises big stories, and attempts at answers, in exchange: a return to form for legendary Stedman and her many fans, a gripping and heart-stopping exploration of family, loss, and love. –JH

Mark Oppenheimer, Judy Blume: A Life

Mark Oppenheimer, Judy Blume: A Life

Putnam, March 10

“For more than fifty-five years her work has done something revolutionary: it rewired the world’s expectations of what literature for young people can be—frank, candid, earthy, and unafraid to show the messier sides of humanity.” Now Oppenheimer brings readers the woman behind the literary empire—through extensive interviews with Blume herself, access to her papers and correspondence, and even analysis of her beloved novels. Detailing her childhood, marriages, heartaches, and “unabashed sexual experiences,” readers will learn more about the beloved author than ever before. –EF

Beryl Bainbridge, An Awfully Big Adventure

Beryl Bainbridge, An Awfully Big Adventure

McNally Editions, March 10

Frequent Booker-shortlistee Beryl Bainbridge was the author of many brilliant novels filled with clever, witty characters and keen observations on human foibles, In her most famous novel (which is also a dark little film starring Alan Rickman and Hugh Grant), a shabby, scandal-steeped repertory theater company in Liverpool rehearses for their Christmas performance of Peter Pan. There’s young actress Stella Bradshaw, rakish director Meredith Potter, dashing lead P. L. O’Hara, and a whole lot of drama. This reissue, with an introduction by Yiyun Li, is a great introduction to the author. –EF

Evelyn Iritani, Safe Passage: The Untold Story of Diplomatic Intrigue, Betrayal, and the Exchange of American and Japanese Civilians by Sea During World War II

Evelyn Iritani, Safe Passage: The Untold Story of Diplomatic Intrigue, Betrayal, and the Exchange of American and Japanese Civilians by Sea During World War II

FSG, March 10

Evelyn Iritani’s in-depth history recounts the little known story of prisoner exchange in WWII, an excruciatingly delicate, fraught diplomatic undertaking that saved the lives of thousands. In the fall of 1943, as war raged in the Pacific theater, American diplomat James Keeley engineered the return of more than 10,000 Americans caught behind enemy lines in Asia, doing whatever it took (even uprooting Japanese immigrants to the Americas) to secure the safety of his fellow citizens. A testament to what is possible, even in the direst of times. –JD

Lindy West, Adult Braces: Driving Myself Sane

Lindy West, Adult Braces: Driving Myself Sane

Grand Central Publishing, March 10

As Lindy West was finishing shooting the TV series based on her best-selling book Shrill, a beacon of women’s empowerment celebrating women who aren’t thin, straight, and compliant, she was also suffering from depression, dealing with her marriage falling apart, and then decided that just then would be a good time to get braces. In an effort to rediscover herself, West takes a solo cross-country road trip. West is one of our best memoirists, funny and truthful in a way we’re always rooting for her. –EF

Alice Hoffman, ed., The Best Dog in the World: Essays on Love

Alice Hoffman, ed., The Best Dog in the World: Essays on Love

Scribner, March 10

This anthology celebrates the best member of the family: the dog! Contributors include Isabel Allende, Bonnie Garmus, Roxane Gay, Emily Henry, Jodi Picoult, Elizabeth Strout, Amy Tan, Paul Yoon, and more. Who wouldn’t love to read these authors on getting a puppy, saying goodbye, and loving everyone’s best friend? –EF

Avery Curran, Spoiled Milk

Avery Curran, Spoiled Milk

Doubleday, March 10

I’m never not hyped for some queer goth horror. And it’s a boarding school ghost story? I don’t want to use the words “dark academia” because honestly, I’m a little over it. But this one looks so fun and spooky. –OS

Sarvat Hasin, Strange Girls

Sarvat Hasin, Strange Girls

Dutton, March 10

A relationship autopsy of a toxic friendship? I am present. I have arrived. I am sitting quietly and politely and waiting for you to tell me more. Strange Girls is about two women who haven’t spoken in a decade being forced back together for a mutual friend’s bachelorette party. As the women try to understand what happened all those years ago, they’re forced to relive their pasts and reexamine what they meant to each other. If you’re an ambitious person and you’ve ever had an equally ambitious but slightly more insane best friend, you know what kind of trouble this can lead to. Hasin’s novel sounds messy and intimate in all the best ways. I’m sitting so quietly and politely waiting for this book and I’m not foaming at the mouth at all. –MC

Andrew Martin, Down Time

Andrew Martin, Down Time

FSG, March 10

Fans of Andrew Martin, of which I have long been one, will be gratified to find that this is his best and biggest book so far, a clever, rigorous, and relentlessly, unfortunately, accurate portrait of how it is to be alive and in your thirties and trying to make art, or at least love, or at least some kind of a difference to someone, in this godforsaken world and decade. Maybe it’s a better description to say that this is the only novel about the pandemic that I have, to date, truly enjoyed, and it is to Martin’s great credit that he manages to avoid the pitfalls of the genre, and instead use the trappings of the story we all know too well to tell us something very specific about a few imaginary people, and something very universal about our own real selves. –ET

T Kira Madden, Whidbey

T Kira Madden, Whidbey

Mariner, March 10

T Kira Madden’s debut novel (after her memoir, Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls) opens with Birdie, on a ferry to Whidbey island, where she is going into a kind of hiding after many years of living in fear of the man who molested her when she was a child—a man who is the subject of a new, best-selling book. You think you know where this is going, but you don’t—you really don’t. Quickly, the book opens up, and up, and up, unpicking the long trail of trauma, not just for Birdie, but for a satisfying constellation of characters, all of whom glitter with life.

When I say this is a novel about the many facets of pain, and the way our culture treats the wounded, and the reverberations of sexual violence against children, it makes it sound tough to read, and in places it is harrowing, but mostly the book is simply so good—so well-written, so thoroughly imagined, so full of beautiful sentences and perfect, evocative detail—that you can’t help but keep turning the pages. It is an empathetic, hard-edged, generous, complicated epic, like something Patricia Highsmith might have written if she actually cared about other people, like Rebecca Makkai by way of Dorothy Allison. I loved it. –ET

Robert Coover, The Universal Baseball Association

Robert Coover, The Universal Baseball Association

NYRB, March 10

An overdue reissue of maybe my favorite Coover novel, which is about a man and his fantasy baseball game… and the epic reaches to which the story of his one-man league might go. I have loved this book for a very long time and, like most Coover, it can’t quite be described. But trust me when I say you’ll never look at fantasy sports (or TTRPGs) the same way. –DB

Charlotte Wood, The Natural Way of Things

Charlotte Wood, The Natural Way of Things

Riverhead, March 10

This dystopian feminist parable by the much-garlanded Wood (Stone Yard Devotional) won Australia’s Stella Prize upon its original publication a decade ago, and I’ve been hearing reports of its brilliance ever since. The setup is like something from a dark fairy tale: a group of women awake from a drugged sleep to find themselves imprisoned in a compound in the middle of the desert, forced to do hard labor in the sweltering heat. The only thing that links the women is that, in a previous life, each was embroiled in a sex scandal with a powerful man. –DS

Will Self, The Quantity Theory of Morality

Will Self, The Quantity Theory of Morality

Grove Press, March 10

The English writer Will Self is known for his prolific ephemera and high-concept, avant-garde modernist works. This new satire is a sequel to his first collection, and 34 years in the making. Concerning some “middle-class, middle-English” characters who are trapped in a carousel of dinner party small talk and well on the way to spiritual rot, this sounds like the bourgeois morality tale we’ll deserve in 2026. –BA

Karan Mahajan, The Complex

Karan Mahajan, The Complex

Viking, March 10

Long in the works, long anticipated by his fans, Karan Mahajan’s The Complex comes out in March, ten years after his critically-acclaimed The Association of Small Bombs. This, in my opinion, should be a practice shared by more authors: taking their time to weave something intricate and deep, then handing over a sprawling masterpiece, ala Kiran Desai, ala M. L. Stedman. Mahajan has created something savor-worthy: a family epic that takes place in both India and America, as the Chopra family attempts to keep itself together in the face of political unrest and relationship fractures. Mahajan writes with grace and precision, is able to depict both horrors and joys, violence and tenderness in equal measure: the arrival of The Complex is sure to be a literary event. –JH

Lore Segal, Still Talking: Stories

Lore Segal, Still Talking: Stories

Melville House, March 10

The late Segal wrote about unlikely and enduring friendship with dignity, care, and wit. Her last published collection, Ladies’ Lunch, followed a flock of Manhattan nonagenarians who’ve kept the pal flame lit for decades. Still Talking, her final book, will star the same wonderful characters motoring through their days on tides of chat. If you’re the type to pine after future, better seasons of And Just Like That…, I’d place this top of pile. –BA

Kōbō Abe, tr. Mark Gibeau, The Traitor

Kōbō Abe, tr. Mark Gibeau, The Traitor

Columbia University Press, March 10

Kōbō Abe is one of my favorite writers, and I’m really looking forward to this previously untranslated book that is “part historical fiction, part detective story.” This novel is Abe’s exploration of loyalty and adaptation in a changing political world, published in 1964 when younger Japanese were starting to ask their parents about the war years. The Traitor unfolds in layers of retelling: a writer meets a military policeman turned innkeeper, who is obsessed with a 19th century admiral named Enomoto Takeaki. The innkeeper is also reckoning with his involvement in a murder during WWII, and how it is reflected in a manuscript about someone betrayed by Enomoto. The Traitor was controversial when it was released for what readers thought it was saying about Japan. All of Abe’s writing, even his strangest and most absurd books, is deeply reflective of his contemporary world. –JF

Lynne Tillman, Paying Attention

Lynne Tillman, Paying Attention

David Zwirner Books, March 17

I have long been a fan of Lynne Tillman’s delightful short stories, which are always surprising and just the right amount of weird. So of course I’m excited about her new essay collection, which gathers 40 years of her writing about art and culture, from critical perspectives on film, art, poetry, photography and fiction, to thoughts on illness, aging, consciousness, modernity, cultural politics, and much more. –JD

Mieko Kawakami, tr. Laurel Taylor and Hitomi Yoshio, Sisters in Yellow

Mieko Kawakami, tr. Laurel Taylor and Hitomi Yoshio, Sisters in Yellow

Knopf, March 17

New Mieko Kawakami alert! Sisters in Yellow is a novel about four women who open a bar together in 90s Tokyo. It’s an exploration of Tokyo’s underbelly and the nightlife industry that’s more interested in being real than sensationalist: Kawakami’s novel is about the painful realities of a rapidly-modernizing world, the difficulty of creating community on the fringes, and the ways we struggle to care for each other and ourselves. I’d be excited to read about this story from any author, but in Mieko Kawakami’s hands this is sure to be a masterpiece. –MC

Antoine Volodine, tr. Alyson Waters, The Monroe Girls

Antoine Volodine, tr. Alyson Waters, The Monroe Girls

Archipelago, March 17

Volodine is responsible for one of the most fascinating and ambitious projects in literature right now: he and several other pseudonyms (if, indeed, Volodine is even his real name) have been crafting an expansive look at something called post-exoticism. There will be a bardo, there will be action sequences rivaling Tarantino (this one features a schizophrenic trying to hunt down the titular paramilitary group), your brain will be bent in new directions—it’s time to discover post-exoticism for yourself. –DB

Caroline Tracey, Salt Lakes

W.W. Norton, March 17

Did you know there are over a hundred salt lakes on the Earth’s surface, weird little ecological oddities secreted away in the driest parts of the globe? And did you know they’re disappearing? If you answered no, you’re not unlike writer Caroline Tracey, who became so curious about the phenomenon after encountering it that she decided to write a book. From Kazakhstan to Utah to Australia Tracey takes us on a journey in search of these semi-sacred places, meeting along the way countless people dedicated to preserving them. But as she offers readers the story of the Earth’s disappearing salt lakes, Tracey also shares her own journey of self-discovery, of finding queer love, and of finally making a home. –JD

Bassem Khandaqji, tr. Addie Leak, A Mask the Color of the Sky

Bassem Khandaqji, tr. Addie Leak, A Mask the Color of the Sky

Europa Editions, March 17

In October, after spending 21 years in an Israeli prison, the acclaimed Palestinian novelist and poet Baddem Khandaqji was released and exiled to Egypt, where he was finally reunited with his sister. From his prison cell, Khandaqji wrote two poetry collections, hundreds of essays, and four novels. The most recent of those novels, A Mask the Color of the Sky, won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2024. A story of identity, exile, and resistance, it follows Nur, an archaeologist residing in a refugee camp in Ramallah who discovers a blue ID card belonging to an Israeli citizen tucked inside the pocket of an old coat. Intrigued, Nur assumes the persona of the card’s owner to gain access to excavation sites in the West Bank, and insight into his oppressor. –DS

Asako Yuzuki, tr. Polly Barton, Hooked: A Novel of Obsession

Asako Yuzuki, tr. Polly Barton, Hooked: A Novel of Obsession

Ecco, March 17

The author of the international bestseller Butter, which only made it to English in 2024, is back with an up-to date novel about parasocial relationships, social media, the human hunt for happiness, and yes, of course, obsession. Eriko has a perfect life from the outside, but inside, she’s desperately lonely, and constantly following along with a lifestyle blogger who seems actually happy. When Eriko orchestrates a meeting, she’ll set off a chain of events that will send both women into a tailspin. Don’t meet your heroes! –ET

J.M. Sidorova, The Witch of Prague

J.M. Sidorova, The Witch of Prague

Homeward Books, March 17

Magical realism set in Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring? Say no more! (But in case you need more, it’s the first release from Homeward Books, a playful and genre-busting new press—and we can always use more small presses making beautiful and weird books!) –DB

Maile Chapman, The Spoil

Maile Chapman, The Spoil

Graywolf, March 17

Maile Chapman is an intricate, eerie plotter with a knack for unsettling. Her first book, Your Presence is Requested at Suvanto, brought us to a Finnish convalescent hospital, and left us in the arms of a malevolent surgeon. Her long awaited second novel is another claustrophobic psychological horror with feminist overtones. In 1970s Tacoma, a young girl with a predilection for spooky phenomena is seeing demons. And when these presences follow Mandy, our hero, into a fractured adulthood, they cause fresh chaos. This is a book that takes on the utter strangeness of grief. –BA

Hannah Lillith Assadi, Paradiso 17

Hannah Lillith Assadi, Paradiso 17

Knopf, March 17

“Like all of our dead, Sufien still speaks.” Born in Palestine on the eve of 1948’s Nakba, Sufien is forced to leave his home, constantly moving towards some other place, unmoored. From Kuwait to a small Italian university town, and then to New York and Arizona, his life spans love and loss, grief and success. Assadi’s novels are lyrical and gorgeously original—this novel reads as poetry. –EF

Casey Scieszka, The Fountain

Casey Scieszka, The Fountain

Harper, March 17

I can’t wait to read Scieszka’s debut, which Emma Straub calls “Tuck Everlasting for grown-ups,” and which concerns an immortal woman who comes home to the Catskills on a mission to discover the source of her power/curse—so that she can finally undo it. But others may be looking for the source too, and for very different reasons. Sounds utterly delicious. –ET

Wayne Koestenbaum, My Lover, the Rabbi

Wayne Koestenbaum, My Lover, the Rabbi

FSG Originals, March 17

New work by Wayne Koestenbaum is always something to anticipate: as a poet and a writer (and a reader, if you’re ever so lucky) he is an absolute delight. So it’s pretty exciting that his first novel in 20 years is coming this March, which tells the story of one man’s obsessive psychosexual relationship with, yes, the local rabbi. “Lascivious thrills and uncanny hilarity” have been promised and/or warned of. –JD

Ibram X. Kendi, Chain of Ideas: The Origins of our Authoritarian Age

Ibram X. Kendi, Chain of Ideas: The Origins of our Authoritarian Age

One World, March 17

In his latest book, the National Book Award-winning author traces the rise of the “great replacement theory”—the idea that white people (or men, or Christians, or heterosexuals) are under existential threat—and how it has ushered in a newly authoritarian age. Sure to be bracing. –ET

Thomas Dekeyser, Techno-Negative: A Long History of Refusing the Machine

Thomas Dekeyser, Techno-Negative: A Long History of Refusing the Machine

University of Minnesota Press, March 24

We are, it seems, at the precipice of a new technological dark age; for no other reason than that dozens of billionaires have sunk trillions of dollars into AI, we now seem doomed to outsource much of what makes us human to machines, at a scale and speed hitherto unseen in human history. So, what do we do? Well, even in the face of terrible odds, we resist… BECAUSE WE ARE HUMAN. And if you’re looking for inspiration, please see Thomas Dekeyser’s Techno-Negative: A Long History of Refusing the Machine. We might not win in the end, but even in the attempt to resist, we will salvage some of our humanity. –JD

David Streitfeld, Western Star: The Life and Legends of Larry McMurtry

David Streitfeld, Western Star: The Life and Legends of Larry McMurtry

Mariner, March 24

Western Star is being billed as the “definitive” biography of Larry McMurtry—the legendary author of Lonesome Dove who died in 2021—and it looks like it might actually be able to back up that bold claim. Streitfeld, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, was a close friend of McMurtry’s, and the old Texan gave him “the keys to his past” before he died. McMurtry had many personas—rancher, novelist, Hollywood screenwriter, rare book collector, free speech defender—and Streitfeld’s doorstopper biography looks to probe them all. –DS

Han Kang, tr. Maya West, e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris, Light and Thread

Han Kang, tr. Maya West, e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris, Light and Thread

Hogarth, March 24

The first book of nonfiction published in English by Nobel Laureate Han Kang—including her Nobel lecture, along with other essays, poems, photographs, and diaries. As someone very interested in how Kang’s mind works, I’m looking forward to this. –ET

Louise Erdrich, Python’s Kiss: Stories

Louise Erdrich, Python’s Kiss: Stories

Harper, March 24

Collecting more than two decades of stories from the Pulitzer-and-National-Book-winning author, this is sure to be a perfect entry place for those new to Erdrich’s humanist oeuvre and to delight her longtime fans. Plus, it features illustrations from Erdrich’s daughter, commissioned for the collection! –DB

Morgan Day, The Oldest Bitch Alive

Morgan Day, The Oldest Bitch Alive

Astra House, March 24

I’m a sucker for books narrated by dogs, and this one already has me cracking up from the blurb and cover alone: “Gelsomina is an elderly French bulldog… [who] accidentally ingests an orb of parasitic worms. Approaching death, and filled with new life, she begins to see everything differently.” I have the feeling this is going to be popular in the group chat, if you know what I mean. –DB

Amal El-Mohtar, Seasons of Glass & Iron: Stories

Amal El-Mohtar, Seasons of Glass & Iron: Stories

Tor, March 24

Hand-selling books is a difficult job, so it’s nice to know that most booksellers will barely have finished saying “It’s a collection of fantasy stories from a co-author of This is How You Lose the Time War” before they’ve made the sale. –CK

Giada Scodellaro, Ruins, Child

Giada Scodellaro, Ruins, Child

New Directions, March 24

Winner of the 2024 Novel Prize, Scodellaro’s debut novel is a mosaic that calls to mind both The Waves and for colored girls…, following six Black women in a decrepit apartment complex sometime in the near future. I loved Scodellaro’s story collection from a few years back and I cannot wait to see what this novel has in store. –DB

Eka Kurniawan, tr. Annie Tucker, The Dog Meows, the Cat Barks

Eka Kurniawan, tr. Annie Tucker, The Dog Meows, the Cat Barks

New Directions, March 24

Eka Kurniawan’s Beauty is a Wound is an epic, polyphonic, multi-genre novel, hyperbolic and maximalist in its description of family and love. New Directions calls this new novel Kurniawan’s most “contemporarily relevant book.” Sato Reang has an idyllic childhood until his father forces into him into a life of Islamic piety. Though he initially obeys his father, his adolescence is full of dissent. It is “a psychologically timeless story—anyone who’s ever had an overbearing parent and resented them will relate.” I’m excited for this realist but no less adventurous book. –EF

Jake Skeets, Horses

Jake Skeets, Horses

Milkweed, March 24

Navajo Nation poet laureate Jake Skeets’s work has a way of inhabiting space that makes you think differently about language. His second collection, arranged as a quartet, delves into the effects of climate change on the land and all its inhabitants. If your New Year’s resolution is to read more poetry, start here. –JG

Suzanne Simard, When the Forest Breathes: Renewal and Resilience in the Natural World

Suzanne Simard, When the Forest Breathes: Renewal and Resilience in the Natural World

Knopf, March 31

Suzanne Simard’s 2018 memoir-cum-scientific treatise, Finding the Mother Tree, is one of my favorite books. In the vein of Braiding Sweetgrass, Finding the Mother Tree somehow blended complex scientific exposition with intimate personal deal, creating a revelatory narrative about the interconnectedness of (arboreal) life. Simard’s latest investigates the many and beautiful ways in which forests regenerate themselves, existing as they do in overlapping cycles of life and death; and as she meditates on the incipient adulthood of her two daughters, just as her own mother’s life is winding down, Simard comes to understand that human life is not all that different. –JD

Megan Kate Nelson, The Westerners: Mythmaking and Belonging on the American Frontier

Megan Kate Nelson, The Westerners: Mythmaking and Belonging on the American Frontier

Scribner, March 31

American identity was born of myth, forged in fireside tales of frontier heroism and endless abundance. But insofar as that identity was largely and intentionally anchored in whiteness, many of the real stories—just as mythic, just as legendary—went untold or ignored, simply because the heroes didn’t have the right skin color. With The Westerners, Megan Kate Nelson seeks to redress those elisions, uncovering a diverse and magnificent cast of characters whose lives are just as important to the story of the west as any blue-eyed cowboy: from Cheyenne chiefs to biracial fur traders to women ranchers, The Westerners makes room for everyone. –JD

A.M. Gittlitz, Metropolitans: New York Baseball, Class Struggle, and the People’s Team

A.M. Gittlitz, Metropolitans: New York Baseball, Class Struggle, and the People’s Team

Astra House, March 31

Anyone with the misfortune to be born and raised a Mets fan believes that it’s distinct from other sports fandoms. A line from this Hazlitt piece from 2015 has stuck with me for a decade now: “The Mets are not so much a baseball team as they are a long-running dramatic play that has little to do with winning baseball and everything to do with being the living embodiment of endless pain.” They’re a team that wouldn’t exist if the Dodgers hadn’t vacated Brooklyn for greener pastures, eternally playing in the shadow of their crosstown rivals—the winningest team in the history of the sport. Even the Mets’s sole championship in the last half-century was won via the single most tragi-comic fielding error in the history of baseball.

There’s New York sports fans exceptionalism, and then there’s whatever Mets fans have going on. Exceptionalism but for being something worse than cursed—fated, maybe—for a specific brand of suffering. It’s not better than winning, or necessarily nobler, but there’s a kind of comfort in the apparently endless cycle of heartbreak. I’m looking forward to this book confirming all of my priors about my favorite baseball team, and everything they represent. –CK

Adam Phillips, The Life You Want

Adam Phillips, The Life You Want

FSG, March 31

I don’t know about you, but On Giving Up discourse dominated my 2024. In his previous book, Phillips, a British psychoanalyst, offered a round, well-researched rebuke to the West’s ambition obsession. When is hesitation useful? And why the stigma against dropping the people, goals, and activities that don’t serve?

The Life You Want picks up where that compelling project left off. But this collection unpacks ambition on a personal level. Through literature and his native tongue, psychoanalysis, Phillips considers: where do our deepest desires come from? –BA

Maria Adelmann, The Adjunct

Maria Adelmann, The Adjunct

Scribner, March 31

I’ve been eagerly awaiting new Maria Adelmann since reading her last novel, the spectacular fairy-tale riff that was How to Be Eaten. This one looks like a #MeToo campus tale, about an adjunct running into her old PhD advisor who just so happens to have written a book about his past that might feature the adjunct and their dalliance. I’m expecting something funny, sharp, and a little shocking. –DB

Tana French, The Keeper

Tana French, The Keeper

Viking, March 31

“New Tana French” may be all you need to know, but in case you need more, The Keeper is French’s third (and final) Cal Hooper book, and begins in a classic manner: a young woman in a small town (in this case, of course the Irish village of Ardnakelty) mysteriously winds up dead. The tragedy sets the town ablaze, and of course, retired American cop Cal—despite his ongoing desire for the quiet life—finds himself in the middle of it. But really, who cares? New Tana French! –ET

Yann Martel, Son of Nobody

Yann Martel, Son of Nobody

W.W. Norton, March 31

In the latest novel from the bestselling author of Life of Pi, a Canadian academic at Oxford discovers a forgotten Greek epic, about a goatherd who leaves his family behind to go fight in the Trojan War. Since our academic has himself left his family behind, he finds a certain resonance in the story as he pieces it together, fusing together the ancient and modern worlds, and the concerns that unite us all. –ET

Colm Tóibín, The News From Dublin: Stories

Colm Tóibín, The News From Dublin: Stories

Scribner, March 31

I think Colm Tóibín’s short stories are just as brilliant as his novels. Some of these stories were originally published in the New Yorker, but some are brand new. Featuring families across Ireland, Spain, and America, Tóibín is an author with incredible empathy for the human condition and these stories will be a perfect read for anyone who cares about the short story form. –EF

Woody Brown, Upward Bound

Woody Brown, Upward Bound

Hogarth, March 31

An interlocking, polyphonic portrait of a community often overlooked: Upward Bound is set at an adult daycare community for disabled people in Los Angeles. Each client, and each staff member, is there for a reason: never anyone’s best-case-scenario to have to spend one’s days in such a place, but there they all are. There’s a range of disabilities, and a range of expertise on the part of the staff to take care of its clients: a range of emotions, of histories, of thought-patterns, of ways of being. Each is distinct and immersively imagined by author Woody Brown, himself a non-speaking person. It’s a startlingly unique and fresh perspective on the world: we’re lucky to exist inside Brown’s creation, a deeply heartfelt exploration of humanity. –JH

Lisa Lee, American Han

Lisa Lee, American Han

Algonquin, March 31

In this debut novel, two siblings are the perfect “model minorities”—until they aren’t. Viet Thanh Nguyen calls it “a pulsating signal from the liminal zone where the American dream meets the American nightmare,” and Percival Everett calls it “a fantastic sleight-of-hand” and “a beautiful, important novel that will leave a mark,” and these, my friends, are very good blurbs. –ET

Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Night Owl

Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Night Owl

Ecco, March 31

Aimee Nezhukumatathil is one of our great nature poets, and reading her work always makes me feel more connected to the outside world in all its textures. (Crucially, she’s also very funny.) Night Owl is a collection of nocturnes that “plumb the depths of nighttime.” I have no doubt that it will be a beacon in the dark. –JG