Lit Hub's Most Anticipated Books of 2020

A Look Ahead at the Year in Reading

JULY

Ben Ehrenreich, Desert Notebooks

Ben Ehrenreich, Desert Notebooks

Counterpoint, July 7

The past few years of an accelerated, increasingly destructive climate crisis have brought a number of books that struggle to respond accordingly to a crisis of such magnitude; several writers have met this existential challenge with an equally existential discussion of the ways that the climate crisis affects our understanding of human history and time itself. Ben Ehrenreich, a columnist for The Nation, takes this discussion to the American southwest, examining the intersection of science, mythology, and landscape in the desert, in particular in Joshua Tree and Las Vegas. In these settings, Ehrenreich’s book reflects on the ways that the prospect of extinction has affected our understanding of time, and how we use that shift in perspective as we move forward. –Corinne Segal, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Leila Slimani, Sex and Lies

Leila Slimani, Sex and Lies

Penguin, July 14

Five years ago, in Morocco for the publication of her bracingly erotic first novel, Adele, Leila Slimani had a series of unexpected conversations. I know what your book is about, Slimani’s childhood nanny said to her, I could tell you stories. Later, at an event at a bookshop, a sex worker approached the author and said something similar. Slimani’s novel—published last year in the US as Adele—told the story of a recently married woman in Paris who spirals toward oblivion through a series of increasingly risky sexual encounters. It’s not hard to see why it’s publication in Arabic would provoke a reaction.

Slimani began her writing life as a journalist, so she paid attention to what she was hearing, and began a series of interviews with Moroccan women of all kinds about the secrets they kept amongst each other in their sexual lives. Sex and Lives is the result of these conversations, which proceeded over several trips. Slimani keeps a light presence in the interviews, not unlike Svetlana Alexievich’s conversations with former Soviet women soldiers remembering their role in World War II, so the effect is an ensemble portrait of women drawn together through the force of pressures they all face. Each interaction, like this one, excerpted in the power issue of Freeman’s, is potent with the force of that pressure being briefly lifted. –John Freeman, Lit Hub Executive Editor

Andrew Martin, Cool for America

Andrew Martin, Cool for America

FSG, July 7

If you read Andrew Martin’s debut novel Early Work, which came out in 2018, you might just recognize a few of the characters—and more than a few of the themes—in his follow-up, a short story collection about making art, thinking about making art, and also trying to be a person (sometimes in the company of other persons, sometimes whilst, you guessed it, making art). I know I’m making it sound insane, but just read the title story and I think you’ll be convinced. –Emily Temple, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Stephanie Soileau, Last One Out Shut Off the Lights

Stephanie Soileau, Last One Out Shut Off the Lights

Little, Brown, July 7

These quietly moving stories are set in the backwater of the winding down Louisiana oil economy, where the climate crisis is a new destructive force: wetlands are dying and whole towns are becoming unlivable. The characters in Soileau’s struggle to live in a world where home is a tentative thing, searching for purchase elsewhere in their lives. Enchanting and so neatly planed they feel made by time, this book marks the debut of a writer to watch. –John Freeman, Lit Hub Executive Editor

Lynn Steger Strong, Want

Lynn Steger Strong, Want

Henry Holt, July 7

Lit Hub contributor Lynn Steger Strong’s second novel centers on an overworked, overeducated, and underpaid woman living in New York, who reconnects with an old friend at what may be just the right moment. Leslie Jamison called it “a fierce, funny, and consistently surprising exploration of friendship, bankruptcy, motherhood, and that slippery thing we call privilege,” and wrote that “the voice is electric and nuanced; it feels possessed by a rare, inexplicable urgency. It’s less that this novel peels away the surfaces of daily life―school pick-up, subway commutes, vomiting toddlers―to expose the deeper truths dwelling underneath, and more that it exposes the ways those deep truths already saturate every crevice of our day-to-day lives.” Sold. –Emily Temple, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Yaa Gyasi, Transcendent Kingdom

Yaa Gyasi, Transcendent Kingdom

Knopf, July 14

Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing, the story of the slave trade’s toll on a family lineage across three centuries, was a stunning, sweeping debut; Ron Charles of The Washington Post described Gyasi’s style as “agile enough to reflect the remarkable range of her first novel.” I’m eager to read her next book, the story of a Ghanaian family set in Alabama whose protagonist studies neuroscience at Stanford University and recently lost her brother to a heroin overdose. That deep loss raises questions about the abilities of faith and science to address human suffering; addressing those questions is an ambitious undertaking, one for which Gyasi seems uniquely suited. –Corinne Segal, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Sarah Gerard, True Love

Sarah Gerard, True Love

Harper, July 7

In the latest novel from the author of Binary Star and the acclaimed 2017 essay collection Sunshine State, a struggling writer drops out of college to start over and find love, and burns her way through a cast of outrageous and dismal characters as she does so. Which, you know, relatable. –Emily Temple, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Juan Felipe Herrera, Every Day We Get More Illegal

Juan Felipe Herrera, Every Day We Get More Illegal

City Lights, July 14

Syncopated by a series of song-like addresses to a firefly on a road north, this dexterous and luminous new book by former US Poet Laureate is part Basho, part protest poem. Herrera’s roving eye captures all, from moments of ephemeral calm, to the way workers work—Herrera, the son of migrant farm workers, laments how hard it has been for high culture to even regard people like them. The migrants who travel in shadows. Here as in other books, Herrera has stripped punctuation from many of the poems, leaving them to blow as if a holy wind moves through them. A prolific voice for justice, Herrera continues to see the world with compassion, a goofy sort of humor, and a liberationist’s roving kind of care. These are warm poems for hard times. –John Freeman, Lit Hub Executive Editor

Lacy Crawford, Notes on a Silencing

Lacy Crawford, Notes on a Silencing

Little Brown, July 14

Lacy Crawford, writer, wife, and mother, thought she had put the sexual assault she survived at age 15 behind her. But when Crawford heard that her old alma mater, the elite St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, had come under state investigation after widespread reports of sexual abuse on its campus, she got in touch with the detectives—and soon found out how extensive the coverup and gaslighting she experienced had become. A riveting story of and for our time. –Emily Temple, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Nicholson Baker, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act

Nicholson Baker, Baseless: My Search for Secrets in the Ruins of the Freedom of Information Act

Penguin Press, July 14

From the very beginning of his writing life, in the brief, brilliant novel, The Mezzanine, Nicholson Baker has approached the process of describing the present as an ever expanding archive of moments. Thoughts and movements so tiny they can expand infinitely all the way down to the quark. In time, Baker moved from such imaginary archives to real ones, such as the rotten piling up stacks of old time newspapers he described rescuing in Double Fold, which won a NBCC award 20 years ago, to Human Smoke, which dug way into the margins of recorded history and found a burgeoning pacifist movement right up until and through World War II. Now Baker has gone to the archive tool on everyone’s mind in our bizarro times, the Freedom of Information Act. Here’s Baker’s account of its history and his own attempt to use it, what he found, what he didn’t. This will make for important context as a blizzard of FOIA requests form, in some cases, one of our only defenses between a lying mendacious president and his next term. –John Freeman, Lit Hub Executive Editor

Chelsea Manning, Untitled Memoir

Chelsea Manning, Untitled Memoir

FSG, July 21

“This is one of the most significant documents of our time removing the fog of war,” Chelsea Manning wrote in 2010, when transferring over 750,000 documents to Wikileaks, arguing what she was showing revealed “the true nature of 21st-century asymmetric warfare.” Adding, “have a good day.” She ultimately spent seven years in prison for refusing to testify against Assange, “fighting to stay alive,” he told the Guardian in an interview a year after her sentence was commuted by President Obama. She now is going to tell her story in a memoir and it is sure to be moving, powerful, explosive, at the heart of so many aspects of American life today. –John Freeman, Lit Hub Executive Editor

Alex Landragin, Crossings

Alex Landragin, Crossings

St. Martin’s, July 28

This genre-bending debut is more than a novel within a novel: it’s a letter from Baudelaire to an illiterate girl, a noir Romance, and the memoir of a deathless queen . . . within a novel. It’s a puzzle box that can be read in two different directions, and as someone who likes a little play (not to mention post-modernism) in their literature, I am awaiting it eagerly. –Emily Temple, Lit Hub Senior Editor

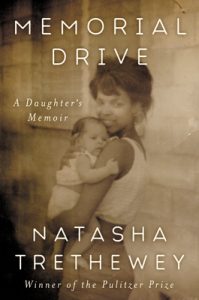

Natasha Trethewey, Memorial Drive

Natasha Trethewey, Memorial Drive

Ecco, July 28

A terrible event she has survived informs so much of Natasha Trethewey’s poems. When she was 19, Trethewey’s step-father shot and killed her mother. Trethewey has said she turned to poetry to understand what had happened. Now she turns to prose. What a devastating story she has to tell; if it is at all like her Pulitzer Prize-winning poems, it will lift and mourn and think at the same time. –John Freeman, Lit Hub Executive Editor

Lauren Beukes, Afterland

Lauren Beukes, Afterland

Mulholland, July 28

I am always here for new Lauren Beukes, but this one sounds particularly good: in a wold in which a pandemic has killed almost all of the men in the world, Cole is on the run across the American west with her twelve-year-old son, who is disguised as a girl to protect him from those who would use him for their own devices—including his own sister. But regardless of plot, you can always trust Beukes to surprise and delight—as long as you’ve got a strong stomach. –Emily Temple, Lit Hub Senior Editor