Our newest podcast series, Future Fables, in partnership with Aesop, offers newly imagined fables that will catalyze both conversation and contemplation. Written by some of today’s most thought-provoking authors, each of these bedtime stories for adults adopts the ancient fable form to help us navigate the complexities of modern life.

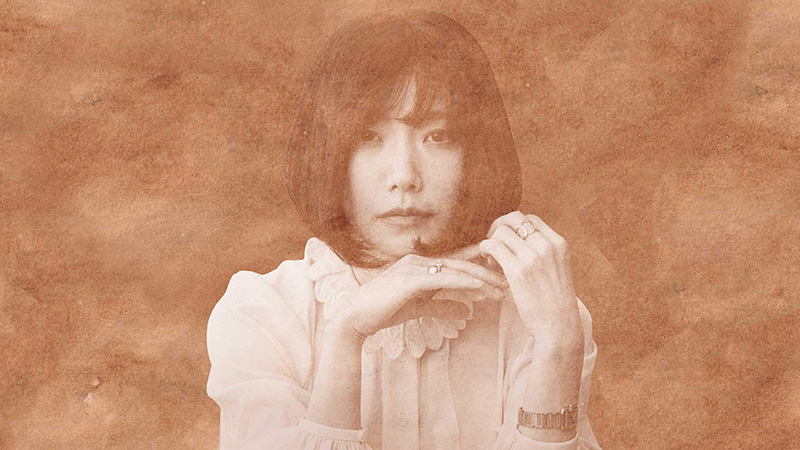

Mieko Kawakami’s Future Fable invites us to reconsider common fears, while underlining the preciousness of friendship.

It was early winter when I saw them again. It happened out of the blue, and I hadn’t seen any of them since they left. A complete surprise. How many years had it been? With the one I hadn’t seen for the longest time, it had to be forty years. But from then on, we’d all get together, sit around the table, sometimes have tea, sometimes take a walk down a mountain path, laugh, maybe lie in bed and just talk, comfort someone when she’s crying, or joke around with one another. I’d met each of them separately, at different moments in my life, and each one of them had died in her own way and in her own time. What they had in common was that they weren’t here anymore. And that, in the time we’d shared together, I’d loved each of them in my own way, as flawed as that love might have been.

The girls started appearing in my dreams all together, as a set. I say “dreams,” but where we met was far more vivid, a place that obeyed a different set of rules from what you find in the dreams that typically come to you in your sleep. Everything had a greater clarity and gravity than reality; I could really taste the food, and both the color and light around us were brilliant beyond imagination. Even after the others had gone and I’d opened my eyes, they stayed with me, leaving an impression as profound as any memory of reality. It felt as if I had truly been there with them. At the same time, when I was at the office with my coworkers, who were supposedly still among the living, they all seemed so flat and lifeless, so utterly gray, that I couldn’t even understand what they were saying.

When I was with the group, it was such a joy—as if I was part of a new community: my grandma, my mom, my editor, my classmate from middle school, my cousin, my dogs Hana and Shan. All of them appeared as I’d last seen them, and even though they belonged to different generations and species, and had lived in different places, that seemed to pose no problem at all, and we always had a wonderful time together. Yet, at the same time, there were so many things that I wanted to know, so I asked. This isn’t an easy thing to ask, but do you know you’re dead? Sure, sure we do, they said, as if they had no idea why I would even bother asking. Like you’re telling someone that a huge typhoon is going to hit this weekend, and they’re just telling you not to worry, it’s definitely going to miss us.

I don’t know how much time had passed since then, but one day I was in a little accident and died instantly. From then on, I spent all of my time with the others. Now I can tell you, with absolute certainty, death doesn’t hurt, not one bit. But, you say, what about accidents and illnesses? Well, that’s what I thought, too, but in reality those things aren’t directly related to death. There’s a clear gap—a distance—between physical pain and suffering on one hand, and death on the other, and that space through which we all pass is actually very pleasant. The pain that you feel up until then is, well, pain, so you can handle it. Anyway, at that point, I’d become a full-fledged member of the group. What’s really interesting is how, on this side, there’s no such thing as sleep. The others don’t sleep and neither do I. We’re always awake, so we started going together to visit another person I used to know so well. At first, she was truly surprised to see us show up like that—but she said she wanted us to keep coming. Then, after some time, she asked the very same question that I’d asked long ago: Do you know you’re dead? Sure, sure we do. And it really wasn’t a big deal, so there wasn’t anything else for us to say.

Eventually, we found one of the girls sleeping. It was my old classmate from middle school. She was curled up, and really did seem to be asleep. We’d all been on this side for so long that we’d forgotten what we were looking at; all we could do was look on as our hearts pounded. We felt like we were witnessing something incredible, something that could never be undone, and yet we were powerless to stop it. She was right there in front of us, but it felt like she wasn’t. And if that was true, then where was she? We formed a circle around her and found ourselves holding hands, watching over her as she slept soundly, her eyelids shut tight. She looked so peaceful, curled up and not moving. There was only the sound of her breathing. None of us could remember what sleep was, what the state of sleep was like, but as we watched her, we started to think that maybe, just maybe, it wasn’t as bad as we thought.

Translated by David Boyd

________________________

Mieko Kawakami was recently shortlisted for the International Booker Prize for her novel Heaven (2009), translated by David Boyd, who also translated this fable.

*

Aesop—the literary-leaning skin, hair and body care brand—has launched a new podcast series which asks the question, what sort of fables might its namesake—Aesop, the ancient Greek fabulist—write in 2022? Featuring compelling stories by some of the most thought-provoking authors in contemporary literature, this series of succinct yet stirring tales may help listeners navigate life’s big questions, with morals for the modern day revealed through fables of river cats, gluttonous caterpillars and ambitious rodents. The podcast is available at aesop.com and wherever you get your podcasts. Subscribe, listen, and enjoy each fable as we bring you Future Fables, presented by Aesop. Episodes will be available for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Amazon Music, Pandora, Google Podcasts, Castbox, iHeartRadio, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Future Fables

Aesop’s inaugural podcast series offers freshly penned fables that may provide catalysts for conversation, contemplation and quietude. Written by some of the most thought-provoking authors of today, each of these bedtime stories for adults adopts the ancient fable form to elucidate morals for modern times. Season one includes fantastical tales by Mieko Kawakami, Rivers Solomon, Akwaeke Emezi, Amelia Abraham and Lydia Millet.