Lily Meyer on Philip Roth, Anti-Zionism, and Her Relationship to American Judaism

“I take both my Jewishness and my Americanness as honors and responsibilities.”

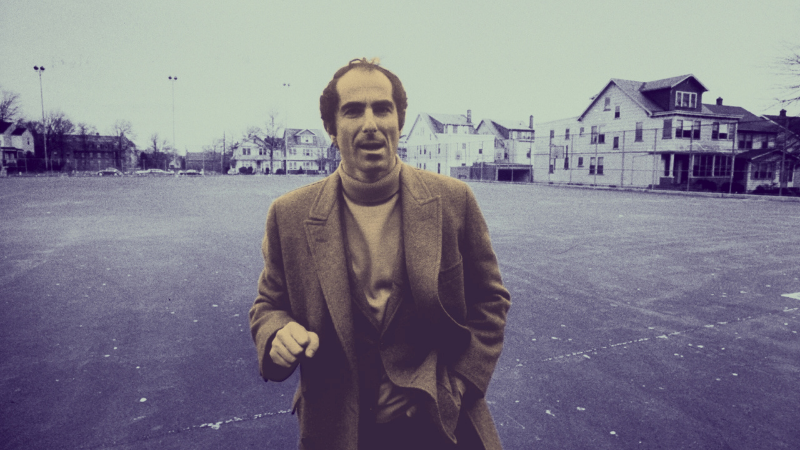

Philip Roth, Zadie Smith writes in her essay collection Dead and Alive, was a patriot. An “unusually patriotic writer,” in fact. Smith met Roth when he was in his eighties, retired from writing, and she recalls that he devoted the bulk of his time to reading American history, especially slave narratives and books about slavery. To Smith, this was emblematic of Roth’s particular version of patriotism. His “love for his country,” she explains, “never outweighed or obscured his curiosity about it. He always wanted to know America, in its beauty and its utter brutality, and to see it in the round: the noble ideas, the bloody reality.”

When I read that description, my scalp prickled. I am—I’m being honest here—a Roth worshipper. No author has influenced me more. I’m always searching for, or aspiring to, reasons to compare myself to him, and here was a comparison that required absolutely no effort. Smith’s description of Roth’s attitude toward the United States corresponds precisely to my own feelings.

All my writing orbits, in one way or another, around the question of what it means to be an American Jew—and I mean really American: committed to the U.S.; dependent on it; stuck with it. Its history is my history, and so I feel driven to know and engage with it as much as I possibly can. If that’s not patriotism, what is?

I got some of this idea from the same place Roth did: the outskirts of New York in the 1940s. He grew up (you know this) in the Jewish part of Newark, New Jersey. My grandfather grew up in Bridgeport, Connecticut, which was smaller but in many ways comparable. In Bridgeport, my grandfather had a childhood that was at once deeply Jewish and deeply American. He kept kosher, went to synagogue, and spoke Yiddish at home; he also went to public school with his Catholic best friend, Eddie O’Hara. (They remained friends their whole lives. Years after my grandfather died, when I went to visit my grandmother, it was always Eddie who drove me to and from the train.)

His brother Leon—who, incidentally, married a high-school classmate of Roth’s—fought in World War II. He missed my grandfather’s bar mitzvah because he was at Camp Crowder, getting ready to ship out. I know this because I have a letter he wrote my grandfather to mark the occasion. I’ve read it so much that I know bits of it by heart.

I don’t buy it. Why would I? I don’t live there.

In the letter, Leon, like any older sibling who wants to be wise, gives his little brother some instructions. He tells him to “remember always that you are a Jew,” but also that “you are first, last, and always an American.” For Leon, these reminders are not just complementary but intertwined: “Don’t forget,” he urges his brother, “that it is because of America that you are able to hold your head up and say, ‘I am a Jew.’

In 1944, when Leon wrote the letter, this was no small thing—and not only because of Hitler. His father had fled antisemitism in Russia, and Stalin’s government later murdered his parents and all seven of his sisters. Today, there are many, many countries where a person can hold their head up and say “I am a Jew,” but that doesn’t make it less meaningful to me that my family gets to say it, and has gotten to say it for generations, because my great-grandfather left Russia for Bridgeport.

My conviction that this fact is relevant to my 21st-century life is the same belief that undergirds the idea of diasporism in Roth’s 1993 novel Operation Shylock. In the view of that book’s fictional diasporists, Jews should be willing to—no: should want to—make a home in any country on earth. Operation Shylock is, famously, Roth’s Israel novel, and he’s more vexed by his characters’ rejection of Zionism than I am.

In fact, my own opposition to Zionism is one of the reasons Leon’s letter means so much to me. One of the cornerstones of Zionist rhetoric, both in Israel and in the U.S., is the argument that Israel is all Jews’ country, all Jews’ home. I don’t buy it. Why would I? I don’t live there. My passport is American. The American government may choose to spend my tax money in support of Israel, but that doesn’t mean I pay those taxes to an office in Jerusalem. It’s the American Constitution that, as Leon wrote to my grandfather, “allows me to practice & enjoy all the freedoms that have become so commonplace” to me. As far as I’m concerned, remembering that I’m “first, last, and always an American” is a means of rejecting the claim, promulgated by antisemites as well as Zionists, that I am anything else.

I take both my Jewishness and my Americanness as honors and responsibilities.

But the Leon letter has another meaning for me, one that became key to one of the main characters in my novel The End of Romance. Leon was my maternal grandfather’s brother. My paternal grandfather was a German Jew from Richmond, Virginia. His ancestors got there in the 1830s. One of them fought for the Confederacy and a later relative proudly preserved Jefferson Davis ephemera. This, too, means I am first, last, and always an American: my family members participated in the bloodiest, most brutal part of the country’s history.

I gave this personal legacy to Abie Abraham, who is The End of Romance’s personification of roots. Abie is a guy who knows his values and lives by them unswervingly. First among those values is the importance of family; in many ways, his ancestry defines his life. He’s a historian of Virginia’s Jews, which means his entire professional career is devoted both to remembering that Jews are Americans and critiquing Jewish participation—very much including his own family’s—in the flawed American project. Midway through the novel, he tells its protagonist, “I’m very simple, Sylvie. I latch onto ideas and don’t let go.” He’s talking about their love story, but he could just as easily be talking about the Jewish patriotism that he and I share.

I take both my Jewishness and my Americanness as honors and responsibilities. I’m grateful to this country for all it has given me and my ancestors: a home, freedom of speech and religion, paved roads, drinkable water, educations. That gratitude, as well as my awareness that my ancestors participated in the effort to take freedoms from other Americans, makes me want to understand the United States as well as I can, and makes me want it to be better. I would like it to someday be a country that any person could write a Leon letter about.

As I write this, ICE agents are kidnapping children from schools in Minneapolis. Our nation is very far from welcoming newcomers. It is precisely for that reason that I can’t think of a nobler ideal to pursue.

__________________________________

The End of Romance by Lily Meyer is available from Viking.

Lily Meyer

Lily Meyer is a writer, translator, and critic. She is a contributing writer at the Atlantic, and her translations include Claudia Ulloa Donoso's story collections Little Bird and Ice for Martians. She lives in Washington, D.C.