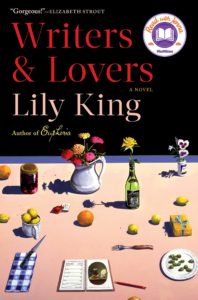

Lily King on Writing the Novel She Needed 30 Years Ago

"But where were the books about women writers? Where were the books about their struggles?"

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

In high school I was fed a full diet of male writers, from Homer to Shakespeare to Wordsworth to Faulkner and Fitzgerald and Hemingway. Plus—because it was New England—a few heavy servings of Cheever and Updike. Not one novel by a woman in four years, only two short stories: “The Grave” by Katherine Anne Porter and “Why I Live at the P.O.” by Eudora Welty. That’s it.

And still, I had my heart set on being a writer.

It was much the same in college in Chapel Hill, except Southern: Robert Penn Warren, Barry Hannah, more Faulkner.

And still.

After I graduated, I sought out narratives about becoming a writer. I read Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Hamsun’s Hunger, McInerney’s Bright Lights Big City. I read these books over and over, these stories of men in their youth struggling to write.

But where were the books about women writers? Where were the books about their struggles?

I was always broke. I was always in debt. I worked restaurant jobs and bookstore jobs and had no health insurance. I started a novel and moved with it every year or two, from New York to Spain to California to New Hampshire.

In my early thirties, I washed up at my older sister’s door in Massachusetts. She took me in and gave me the only space available in the small carriage house that she rented with her boyfriend, a 6×10 storage room next to the front door. I squeezed in a desk and wrote in the morning and waited tables at night. I failed at love again and again. Most of my friends had become practical, had careers and salaries and sturdy relationships. They sent me wedding invitations and, a few years later, birth announcements. Their lives were as incomprehensible to me as mine was to them. In the books I read, those men who want to be writers are seen as tenacious and uncompromising—heroic, even when they fail. But more and more I just felt pitied.

*

The first scene in my new novel is based on something that happened during that time. My one duty while living in that storage room with my sister and her boyfriend was to walk their dog while they were at work. One morning our neighbor, who owned the big house and the carriage house we lived in, was out in the driveway when I was coming back with the dog. I’d been writing since before dawn, and was still in my sweats and hadn’t brushed my hair and was wearing these old slippers with the stuffing coming out.

But where were the books about women writers? Where were the books about their struggles?

He asked if it was true that I was writing a novel.

I told him it was. “Well,” he said, “I think it’s extraordinary that you think you have something to say.”

I went back to my storage room and felt like I’d been clubbed in the stomach. I wrote down his words in my journal, and went back to my novel.

I turned thirty-three, then thirty-four. My sister and her boyfriend bought a house and I moved into it with them. They began the process of adopting a child and I was part of the home visit, the maiden aunt, the “writer” in the attic. I’d sent out my novel to nearly twenty agents and the rejection letters were pouring in. I was having panic attacks by then, and had stopped sleeping.

I finally got some cheap health insurance and took a course they paid for on stress management. I went religiously to that class each week, and did my homework in the workbook they gave us. In the spaces between questions I wrote in small blue script about my physical discomfort: the burning in my chest, the stampeding of my heart, the heaviness of my arms and legs. What is the source of your biggest frustration? “There is so much I want yet the steps are so tiny,” I wrote. One of the assignments, Learning Exercise 18: Reducing Suffering, involved a chart with three boxes. The first box was labeled My Areas of Suffering and inside it I had to describe the difference between What you want and What you have. I wrote that I wanted to be an accomplished writer but that I was an aspiring writer. The next box was Ways to Reduce Suffering and below it a list of options: Forgiveness, Acceptance, Gratitude, Wisdom. I circled Acceptance. In the final box, My Specific Actions, I wrote, “To be an accomplished writer is a process. It will probably take my entire life. I simply have to keep writing.”

*

When my mother died suddenly, four years ago, I was working on a novel about a writer in 1901, traveling with his mother. I had done months of research for this book and liked the pages I had so far, but after my mother died I stopped writing fiction. I feared that desire would never come back, and when it did, nearly a year later, I could not return to the story of the young man and his mother in 1901. I could not even open the notebook with the first chapters in it. There was only one thing I wanted to write: the novel I needed to read in my twenties and thirties, a story of a young woman struggling to become a writer.

I wrote, “To be an accomplished writer is a process. It will probably take my entire life. I simply have to keep writing.”

I’ve been wondering lately why, when I was grieving my mother, this was the story that came rushing out. I think it’s because that time in my life felt like a time of mourning, too. I felt the same loss of control, the same acute vulnerability to life itself. I can see now that when I was thirty-four and filling out that stress workbook, I had begun to grieve my own dream. I wrote this new novel for her, and for all the women in driveways in old slippers, and anyone hanging onto a dream they fear is fading away.

__________________________________

Writers & Lovers by Lily King is available now via Grove Press.

Lily King

Lily King’s novels include The Pleasing Hour, The English Teacher, and Father of the Rain. Her most recent, Euphoria, has won numerous awards and was named one of the ten best books of 2014 by the New York Times Book Review, is being translated into numerous languages, and will be a feature film.