Like Writing, Cruising is an Exercise in Introspection and Perseverance

Alex Espinoza on Discovering His Sexuality

Like so many of us, my first introduction to the concepts of puberty and sex came by way of a grainy film reel I watched in the cafeteria of my elementary school along with the rest of the boys in my class. We had to get a signed permission from our parents to see it; many of them didn’t speak English, including my own.

“It says it’s for a film they’re going to show us,” I translated the slip for my mother.

I remember her squinting, trying to mouth the words, even though she had no clue how to read. “Why do they want my permission now?”

I said something like, “This one’s different. I think it has stuff about guns and nuclear bombs.”

Of course, she believed me. I was her consentido; she often pampered and doted on me, something she never did to the rest of my siblings. This was in part due to my alopecia, an incurable condition that results in prolific hair loss, and a physical disability that drastically limits the use of my right arm. I was her youngest, the one closest to her. She kept me near her at all times, saw to it that we didn’t miss the endless medical appointments where I was stripped down to my underwear, poked and prodded, my body a source of curiosity and spectacle for the constant stream of doctors and nurses in the examination rooms.

I was taught to be a good kid, to be obedient. I was devoted to my church, attended morning Mass at Saint Louis of France each Sunday, excelled in my catechism classes, so much so in fact that, in my naïve mind, I imagined myself going into the priesthood. Because who else would care for me but my mother and God? Both loved me unconditionally. I had to do everything they said. Failure to comply would spell doom and lead to nothing but eternal damnation of my soul. It was the first time I recall intentionally lying to my mom. She signed the form; her crooked letters barely forming shapes that resembled her name.

Despite my devotion to God and the church, despite my mother’s lectures about the spoils of sin and her constant reminders that I was “different,” that I would grow up to be a righteous and devout man, that I would (unlike my trouble-making siblings) make her proud, there stirred within me a desire to explore, to know, to experience those things she warned me against.

I watched that reel along with an auditorium full of sweaty and nervous sixth-grade boys, each of us transitioning into something resembling manhood. It showed a couple with feathered hair and bell-bottom jeans roller skating and eating burgers at a diner then driving around in a Trans-Am and parking on a cliff overlooking the city. They hugged and kissed to Rod Stewart’s “Tonight’s the Night.” There were crude graphics of a flaccid penis becoming erect as blood flowed through its narrow shaft. Some of us giggled. Other muttered “gross.” I recall neither giggling nor turning away in disgust. I remember being fascinated and not knowing why. I wanted to know why the dick in the drawing didn’t look like mine. Maybe, I wondered, like my alopecia and my disability, there was something wrong with my own.

I learned at a young age that to be disabled, to be born “different” meant that I would continually be touched, prodded, and invaded in multiple ways—by hands, by eyes, by words.

I remember worrying about this so much that I lost sleep over it. I took multiple trips to the bathroom to make sure everything was alright down there. I had nightmares where I imagined it falling right off in front my entire class as I led us in our morning recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance. Too afraid to ask my mother or my brothers, I summed up the courage one day during a doctor visit to mention it to the nurses when we were alone and prepping me for a series of new x-rays.

“How do you mean it’s different?” She stopped what she was doing, folded her arms, and stared at me.

I somehow managed to muddle through an explanation of the film we’d watched a few weeks before and how the dick in the illustration was not like mine, how the narrator in the strip had said the word “sperm” and everyone had laughed. I was wearing one of those drafty hospital gowns, my feet in a pair of blue Superman socks. She unfolded her arms, reached for the gown and raised it. Then she pulled back the band of my underwear and peeked inside.

“You’re uncircumcised,” she told me. “That’s all.”

She assured me that it was nothing to worry about. Without going into too much detail, that gruff nurse with the cold hands and neat hairdo put my mind at ease, at least temporarily. But it was yet another in a long and tangled string of instances where I believed my body to be abnormal, a source of spectacle and curiosity. I was so accustomed to being studied and examined, unclothed, my flaws and imperfections splayed out for everyone to see whenever they wanted, almost always without my permission. I learned at a young age that to be disabled, to be born “different” meant that I would continually be touched, prodded, and invaded in multiple ways—by hands, by eyes, by words. One of the toughest realities about being different like me is realizing that my disabilities, all the things that make me different and unique, cause disruptions in the larger illusion of our lives. Being disabled means your very presence works to remind everyone else how fucked up life can be, that some of us are forced to move about in a world not engineered for us.

Because I grew up in house full of siblings who loved rebelling, and because I learned to watch everyone around me, I picked up their habits. And the desire within me to go against my mother’s wishes strengthened, my impulse to ignore her warnings and advice intensified. I found subtle ways to revolt. I began questioning the teachings of my church, made excuses for not wanting to attend Mass, and caused a bit of controversy among the girls in my elementary school when it was discovered that I was reading Judy Blume’s Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret. Livid that I was learning about bras and menstrual cycles, a handful of girls formed a committee to protest. The case was brought to our teacher (a female) who decided in favor of letting me continue because she said that I was, “curious and curiosity is a good thing.”

It is a moment that captures something unnamable but feels crucial for survival. It’s an impulse so strong it boils the blood, alters time and reality and sense.

That curiosity grew as I went from elementary school to junior high and then to high school. By then, I had begun to notice that my interests focused on boys—more specifically, older men. The first time I had a sexual encounter I was sitting at a bench waiting for a bus when a young man in his twenties picked me up, drove me to an empty field, and we messed around. He told me about the parks and public bathrooms littered across the area where men were meeting up to exchange blowjobs, handjobs, or more. That was my introduction to the world of cruising, and I was hooked. I found solace and acceptance, a function in those anonymous spaces, where I met up with men for brief and intense encounters.

Sometimes we saw one another, other times these interludes occurred anonymously, in the darkened shadows of an alley or a bookstore or an empty parking lot. In those moments of anonymity, I wasn’t that poor, disabled, insecure Mexican boy hopelessly trying to fit in. In those spaces of transit and transaction, I was a hand reaching out beneath the bathroom stall, I was a pair of smooth, hairless thighs, I was an uncircumcised penis poking out from a gloryhole.

I was an assemblage of body parts, random appendages emerging out from the well of a great darkness. Yet, I never felt more complete, more self-aware than in those brief and erotically intense moments. I could grab and feel. I could take and control what I wanted. And if anybody was going to examine me, explore my body, invade me, it would be on my terms. The cruising space became an opportunity for me to turn the tables on a society that sought to turn my body and my sexuality into a spectacle.

This is how I learned to resist. This is how I fought back. Through my participation in a practice that has existed for centuries—from ancient Greece and Rome to 18th-century England and France to now—I found a subculture willing to embrace me, “flawed” and imperfect as I was. I learned how to communicate not just with words but with movements and actions. I could speak and be heard in ways I’d never imagined.

But you do have to practice patience when you cruise. You need to be alone for long stretches, often looking for something that isn’t always there. It takes time to cultivate this skill. It takes time to learn how to identify the cracks, to see the openings, to recognize the breaks and tears that exist in the ordinary. It’s meditative. The driving around and around in circles, past the same spot. The watching. The waiting. It teaches you how to be still in the moment, how to feel Earth spinning on its axis, how to sense the gravitational pull of the ground beneath your feet. In those moments of feeling and being anonymous, fleeting as they were, I learned about patience and perseverance.

It reminds me of writing. Both require a level of isolation, of quiet solitude. Both ask you to reach deep inside, to look inward, to sit with your memories and thoughts while everything hurls forward and you wonder: What is the pursuit all about? What will be revealed at the end? How will the color of things change when one comes out of the journey? It is a moment that captures something unnamable but feels crucial for survival. It’s an impulse so strong it boils the blood, alters time and reality and sense. And the only way one gets better at both is by returning to it, doing it over and over, again and again.

Cruising taught me how to cultivate a sense of confidence. I learned how to walk a little more slowly in the world. I learned how to watch and wait for the revelations, for the climax, if you will, to come.

Cruising made me write.

_____________________________________

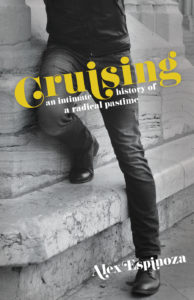

Cruising: An Intimate History of a Radical Pastime by Alex Espinoza is out now via Unnamed Press.

Alex Espinoza

Alex Espinoza is the author of the novels The Five Acts of Diego León and Still Water Saints, a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers Selection. His writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times Magazine, NPR, Salon,The Los Angeles Review of Books, Virginia Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. His awards include a 2014 Fellowship in Prose from the National Endowment for the Arts and a 2014 American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation for The Five Acts of Diego León.