“Like Shooting Fish in a Barrel.” Meet the Men Profiting Off the Medical Fears of Thousands of Women

Elizabeth Chamblee Burch Digs Into the So-Called Holy Grail of Mass Torts

Starting in 2013 more than a hundred thousand women received calls about the urgent need to have surgically implanted pelvic mesh removed from their lower abdomens. These calls came not from doctors, hospitals, or mesh manufacturers, but from a large, noisy room a few miles from Fort Lauderdale’s white sand beaches.

Right off the major throughway of I-95, at the plastic-sounding 1000 Corporate Drive, towered a gleaming seven-story, mirrored glass-and-steel building surrounded by palm trees, a lagoon, and plenty of asphalt. With its marbled atrium and floor-to-ceiling windows, it looked like the natural habitat of the midlevel bankers, salesmen, and project managers who own silk plants, live-tweet Tony Robbins events, and frequent Delta Sky Club lounges.

Instead, the fifth and sixth floors housed the bastard brainchild of Vincent Chhabra and Ron Lasorsa—a 40,000-square-foot mash-up of call center and trading floor. The space hosted a smorgasbord of companies Vince started, which were separate in name only—and often not what their names implied. Alpha Law, LLC, was Vince and Ron’s “law firm,” which wasn’t exactly a law firm but partnered with some real lawyers who were admitted to practice in Washington, DC.

He was the heavy, a boss’s boss—and everyone knew it.

Then there were the two call centers that the Chhabra family ran, PRGI, Inc., and Law Firm Headquarters. And finally the Chhabras’ crowning achievement: Excelium International, Inc., the holding company for all the others.

A chiseled gym rat, Vince favored a colorful unbuttoned Versace style that showcased his chest hair and gold chains. He wore gold-rimmed, rose-colored aviator glasses, his head shaved and glossy, and his goatee meticulously trimmed.

He was the heavy, a boss’s boss—and everyone knew it.

With the offices too small for his liking, Vince converted the executive conference room into his personal suite. Sitting at the head of the long table, he’d lean back in his chair and stroke his goatee while he listened. He talked of making billions of dollars without a hint of irony, said “We’re going to eat their lunch” in any competitive situation, and slammed his fists down in anger to punctuate his points. He appropriated the nearby bathroom for himself, forbidding anyone else from using it. Even pre-Covid, his pockets bulged with hand sanitizer. He had more dispensers placed on the walls around the office and refused handshakes.

Visions of grandeur aside, 1000 Corporate Drive was more like a Star Wars cantina.

Vince imagined the sparkling space would serve as an incubator for his new startup ventures and aspired to take over the top floor. To him, 1000 Corporate Drive was no call center; that term would better characterize his previous dump in Hollywood, Florida. He left behind the mismatched chairs, secondhand desks, and three-year-old computers to start fresh. This office was going to be magnificent. It was a $22,731.75-a-month Class A space designed to attract people “used to making six figures, high-performing salespeople,” he said. “I wanted to attract the best of the best type of people.”

Visions of grandeur aside, 1000 Corporate Drive was more like a Star Wars cantina. According to Ron, to get the lease, Vince partnered with a guy he’d “met in Spain,” a euphemism for prison, who was billions short of Bernie Madoff but cut from the same dollar bill.

The vast space buzzed with energy generated by nearly two hundred operators in headsets, lined up in rows of low-walled, four-by-four cubicles. Choruses of “Are you in pain?” “It’s the mesh.” “Have you been prescribed revision surgery?” “Have you retained an attorney?” echoed throughout.

“It was like a Wall Street boiler room operation,” Ron said, “and it was fucking magnificent.”

*

Before south Florida became a beacon for call centers, it was a mecca for drug and alcohol rehab facilities. As part of their journey to independent living, those in recovery are usually required to find jobs. But employers aren’t lining up to hire people whose records often include petty crime as well as the possession of controlled substances. Enter the call centers.

Many of Vince’s employees were not the high performers he dreamed about. Still, he did his best to polish them up. He instructed them to wear slacks and bought them corporate polo shirts emblazoned with his logo. “We’d get people coming out of rehab, pay them shit, and bonus them. You couldn’t work these guys for more than four hours,” said Ron. They’d often burn out after six weeks. His own son Jarred was among the employees.

At that point, the operator would recite the most intimate details of a patient’s health history to hook her before launching into a few basic screening questions.

Marketing legal services through 1-800 numbers in late-night TV commercials or on highway billboards is old and pricey but effective. To offset costs, sometimes lawyers used cheap overseas labor to screen prospective clients. Having call centers take these “inbound” calls is perfectly legal. What’s not legal is unsolicited “outbound” calls to people who fit specific demographics, like women of a certain age or those who’ve had multiple pregnancies who might be experiencing incontinence issues and are likely to have pelvic mesh.

What happened at 1000 Corporate Drive was mostly the latter, facilitated by Indian companies that US medical insurers hired to manage patients’ electronic records. Buried in those medical records were treatment codes, birthdates, doctors’ names, and surgery dates—a gold mine for anyone who could deliver those leads to mass tort lawyers. All it took was a little nudge from Vince and the promise of a lot of cash. With patients’ hospital records, billing codes, and phone numbers prominently displayed on their computer screens, overseas operators could zero in on a prospective client with laserlike precision. They knew exactly who had mesh.

“Hey, you filled out a form online,” one might say.

“No I didn’t,” their mark would almost always respond.

“Yeah, yeah, you did. Remember when you did X, Y, or Z?” they’d ad-lib. At that point, the operator would recite the most intimate details of a patient’s health history to hook her before launching into a few basic screening questions. If the woman didn’t say the right thing to qualify as a mesh plaintiff, the operator would sometimes coach her about the right answer before transferring the call to 1000 Corporate Drive where Vince’s stateside smile-and-dial telemarketers took over.

*

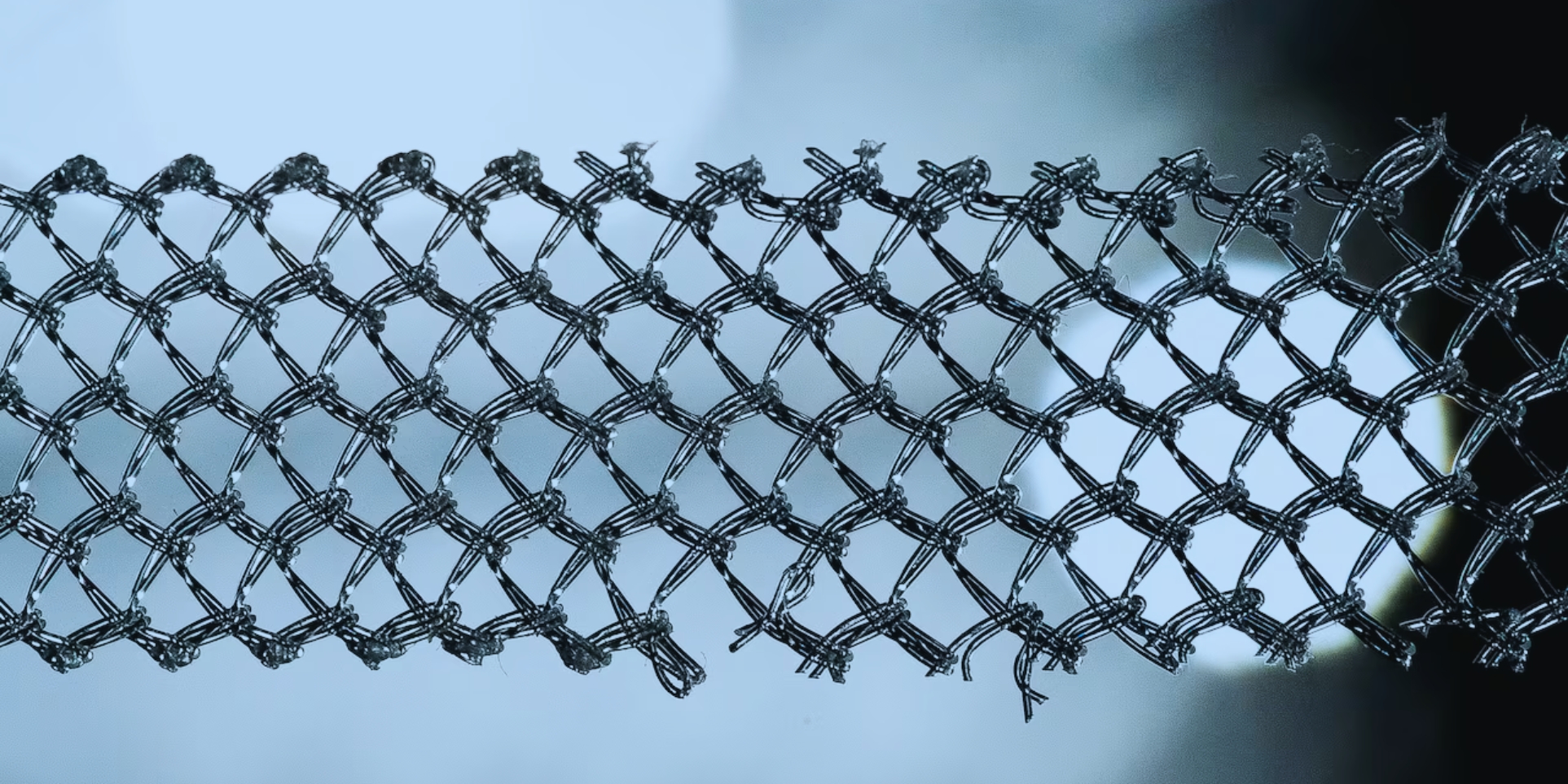

By 2014, pelvic mesh had become the holy grail of mass torts.

Thousands of women had sued the seven mesh manufacturers. Experience with other medical devices like hip implants and pacemakers dictated that plaintiffs who had a faulty product surgically removed had more valuable lawsuits than those with the product still in place. Surgery meant medical bills, missed work, pain, and suffering. Surgery meant bigger settlements. And bigger settlements meant higher attorneys’ fees.

To lawyers who paid Law Firm Headquarters (the Chhabra’s mass tort call center) for client referrals and partnered with Alpha Law (the pseudo law firm Vince operated with Ron), the settlement value of a plaintiff with revision surgery could be worth ten to fifteen times as much as one without. But they needed women like Sharon, Barb, and Jerri to agree to surgery. That was where Vince’s friend Blake Barber came in.

Docs got fast cash and, with inflated charges on the bill, still made more than they would on an insured patient.

Sitting across from the yawning sales desks at 1000 Corporate Drive was a walled-off section of operators run by Blake’s company, Surgical Assistance, Inc. Blake was a towering guy in his midforties with a shaved head who was ballsy enough to say things like “mind your own fucking business” when Ron tried to find out what he was up to. They spoke to each other like outlaws, threatening to fight, shoot, or wrestle each other into submission.

Blake reminded Ron and others around the office of Captain Lou Albano, a crazed pro wrestler from the 1990s who wore Hawaiian shirts, a disheveled goatee, and rubber bands dangling from face rings. Blake didn’t sport face piercings, but at well over six feet tall, he was a hulking figure who often dressed like a Hells Angel and dyed his unruly goatee flamingo pink, Smurf blue, or St. Paddy’s green. His face was tanned from deep-sea fishing, he desperately wanted a capuchin monkey as a pet, and he drove a massive Ford F-350—a truck better suited to general contractors than a former paralegal like him.

If the recovering addicts’ primary task was to filter out women who wouldn’t qualify to sue—namely, those who didn’t have pelvic mesh or who did but weren’t in pain—Blake’s was to amp up the value of their lawsuits (and attorneys’ fees) by convincing them to have their mesh surgically removed.

Blake sent an email advertising his services to all lead plaintiffs’ attorneys on the West Virginia multidistrict litigation steering committee. He and Donna Masi, the assistant at Broward Outpatient Medical Center who called Sharon Gore, would simplify life for women seeking mesh removal by setting up appointments and making travel arrangements. In exchange, all the duo needed was a letter of protection—in other words, a sizable lien against any money a woman might receive from her later lawsuit.

Here’s how it worked: When a frightened woman like Barb, Sharon, or Jerri signed on as an Alpha Law client, she was immediately transferred to Blake’s “different” company, often during the same phone call.

Most of Blake’s operators were part of the same cubicle farm, however. Sometimes it was the exact same telemarketer at 1000 Corporate Drive who picked back up, opened a new script, made a “new” introduction, and launched the litany of questions: “Would you like me to help you get to a doctor that can help you?” “If we could help you get to a qualified medical provider who can help you resolve the issues you are having, would you be interested in seeing that doctor?” “Do you have a few minutes so I can get some information to best tell you how we can help you get to the right doctor for your case?”

Blake overcharged women for travel arrangements and received kickbacks from the doctors; he also worked hand in glove with the medical funding companies that footed the bills in exchange for a hefty stake in the woman’s lawsuit.

Those funders’ business models varied.

LawCash, for example, loaned money on a nonrecourse basis: If Jerri didn’t win her lawsuit against Boston Scientific, LawCash would recover nothing. If she did, it would cash in big-time, recovering not just its initial stake but a heap of interest, too. Depending on the settlement’s size, Jerri might get nothing.

At one point, telemarketers retained two hundred clients a day.

The other model was factoring. Doctors and medical practices who wanted to avoid the hassle and headaches of dealing with insurers, or who wanted to be able to treat uninsured patients, were sometimes open to unorthodox payment methods. Some might accept a lien or letter of protection, which meant they would not be paid until lawsuits like those that would be filed on Barb’s and Sharon’s behalf settled. That could take years.

But there was no need to wait. Surgeons could sell their unpaid medical bills to Blake or one of his medical funding company contacts for 20 percent of the face value. Docs got fast cash and, with inflated charges on the bill, still made more than they would on an insured patient. In turn, the funding company would hold on to the bill (the receivable) and, when a case settled, collect the full payment from the lawyers before the plaintiff recovered any money. If the settlement failed to cover the amount owed, some funders went after the women for the remainder.

Blake had gotten into the factoring business shortly before he filed for bankruptcy on the heels of a divorce. He created Medical Funding Consultants with a former chiropractor named Dr. Ihan Rodriguez, and thought of himself as a modern-day Robin Hood. But some who did business with him saw him as “a scumbag and a son of a bitch.”

He would later pitch potential investors in Medical Funding Consultants with an eye-popping figure: In May 2014, mesh manufacturer American Medical Systems (AMS) agreed to settle 20,000 cases for $830 million. “Approximately 85 percent of the law firm cases in this settlement are non-surgical, meaning 17,000 women did not have surgical care,” he wrote. Women without surgery would get around $15,000, but those whose mesh had been removed would average $230,000 each.

Surgery, in other words, made a $215,000 difference, the bulk of which could be siphoned off to lawyers and funders.

Operators at 1000 Corporate Drive shifted into high gear. If the client hadn’t had her mesh removed, she’d be immediately transferred to Surgical Assistance. From there, she’d receive scare tactics, travel arrangements, a doctor’s appointment with someone who refused to take insurance, and a medical loan concealed within a DocuSign packet programmed to automatically populate her signature and initials throughout without revealing the totality of the packet’s contents.

At one point, telemarketers retained two hundred clients a day.

“Unbeknownst to me,” Ron said later, referring to the hot transfers from India, “we were shooting fish in a barrel.”

__________________________________

Copyright © 2026 by Elizabeth Chamblee Burch. From The Pain Brokers: How Con Men, Call Centers, and Rogue Doctors Fuel America’s Lawsuit Factory by One Signal Publishers, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

Elizabeth Chamblee Burch

Elizabeth Chamblee Burch is an award-winning scholar and the Fuller E. Callaway Chair of Law at the University of Georgia School of Law. A prolific author on mass tort lawsuits, she is also a frequent commentator in national news media such as NPR, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, USA TODAY, and the Los Angeles Times.