Life in Palestine: On the Thriving Artistic Life of Ramallah

“To many writers, Ramallah is an ideal, a dream, a promise.”

Some cities are built from scratch, on empty land. Some seem to have always been there, deriving their importance from their unique location. While others exist only in the imagination, the stuff of legends and tales handed down by grandmothers. Ramallah is not like any of these; a seemingly modest city with a short and relatively peaceful history, it is a city of ordinary stories, rather than heroic myths. To its many, regular visitors, it’s a relaxing place to spend a summer vacation; to its residents, it’s just home. Historians define it as, originally, merely a village near Jiffna, outshone by all the other Palestinian towns, with their richer histories and captivating legends, cities such as Al-Quds, Nablus, Jericho, Al-Khalil, and Gaza. Nonetheless it has remained stoical and quiet in its resistance as well as a welcoming place to live.

And yet, with its unassuming nature and convenient geography—sprawling along a ridge of the Samarian Hills, nearly 3,000 feet above sea level—Ramallah has managed to take its place as a pivotal city in modern Palestinian life. To historians from afar, this might seem like an accident, but it’s an accident that a lot of thought and planning has gone into.

Located in the heart of the West Bank, 16 kilometers north of Al-Quds, Ramallah’s city limits cover an area of approximately 18,600 dunams and provide home to 70,000 people. Around it are an additional 80 satellite villages, refugee camps and other small hamlets. The Governorate of Ramallah and Al-Bireh (it’s neighboring city) is home to 370,000 residents in total. Indeed, the boundary between the cities of Ramallah and Al-Bireh is indistinguishable; the buildings and streets of the two cities intertwine, making them feel like one city. And even though Al-Bireh is larger, both in area and population, “Ramallah” is the common name for the wider conurbation. In reality, the two cities are two completely different places, under two different local administrations with different economies, cultural traditions and social attitudes. Let’s put it this way: you can sip a glass of whiskey in a bar in Ramallah, something that you could never do only a few meters away in Al-Bireh.

Ramallah is host to several important government ministries, not least the Mukataʿa compound, the Palestinian Legislative Council Building, and the headquarters of the Palestinian Security Services in the West Bank. This means that Ramallah is the political center of modern Palestine—a kind of de facto, if unrecognized, capital. The only thing that casts this status in doubt is the historical and political status of Al-Quds among Palestinians. Perhaps because of this uncertainty, Palestinians, in general, have an ambivalent relationship with this city, which acquired its pivotal status only after the Oslo Accords, in the so-called “Oslo Years” (1993-2000). This ambivalence to Ramallah and its status is part and parcel of Palestinians’ ambivalence to the Oslo Accords themselves, which created a short-term peace (of sorts), and allowed for some self-government, but led to no long-term plan, or any restoration of the kind of free movement enjoyed by Palestinians before the First Intifada. (Although Ramallah was designated an “Area A,” in the Oslo II Accord, meaning it had full civil and security control, and was out of bounds for Israelis, the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) still dominate the network of roads surrounding it, many of which are bypasses that only Israeli citizens can use, servicing the many expropriated land settlements that have sprung up throughout the West Bank in the years since Oslo).

To many writers, Ramallah is an ideal, a dream, a promise. Many expatriates returned to the city in the 1990s, in the wave of optimism generated by Oslo, having spent decades in exile, longing to return to at least part of their homeland. Their expectations on returning were sky-high, and were only shattered by the reality they found in the on-going occupation. In his novel I Saw Ramallah, the poet Mourid Barghouti experiences this moment, looking at the gun being carried by an IDF soldier at the crossing: “His gun took from us the land of the poem and left us with the poem of the land. In his hand he holds earth, and in our hands we hold a mirage.” Ramallah represents this mirage, this glimmer of hope that isn’t real, to many writers. Indeed, the popular use of Ramallah in the title of recent novels builds on this set of expectations Palestinian readers have of the city: Ramallah Dream by Benjamin Barthe; Blonde Ramallah, and Crime in Ramallah by Obaad Yehya and so forth.

Looking back through history, references to Ramallah can be found in records as old as Crusader artifacts. Archaeological evidence suggests there was a village here at least as early as the 16th century, under Ottoman rule, and that it began to thrive towards the end of that era, with the first town council recorded convening in 1908. The name “Ramallah” can be traced back to at least 1186 and is formed from the conjunction of the words raam, meaning hill, and Allah, meaning God. Thus, the importance of “God’s hill” might always have been its geography being perched on a hilltop ridge, with cool updrafts, and spectacular views in all directions. People in Ramallah will swear that standing on their roofs, they can see the beaches of Yaffa, Akka and Haifa, beauty spots most Palestinians can never see.

When you travel to Ramallah from the south, from Al-Quds or Al-Khalil, before you reach it you are confronted with a crowded road, traffic jams, a checkpoint, towering buildings and chaos everywhere. You know immediately that you have arrived at the famous Qalandia Checkpoint, separating Ramallah from Al-Quds. If it weren’t for politics, the journey between the two cities would take just 15 minutes, but in reality ,it takes one and a half hours. From the checkpoint you pass through Al-Qalandia Refugee Camp and then Kufr Aqab which eventually brings you to Al-Quds Street, which is officially the entrance to Al-Bireh. For all intents and purposes, though, you can say you are now in Ramallah.

Alternatively, if you travel to the city from the north, after similar, if less famous, checkpoints, you pass through the villages of Birzeit and Jifna until finally you reach Al-Irsal Street, to be greeted by the infamous Mukataʿa, complex where Arafat was besieged by the IDF for two years and almost entombed by the Israeli bulldozers. Then you head for the heart of the city, to a confluence of roads and noise that people call Al-Manara Square, where today four lions sit or stand in various poses. Originally the monument consisted of five lions at the base of its pillar, which, according to legend, represented Jerias, Shqair, Ibrahim, Hassan and Haddad, the five families descended from Rashid Al-Hadaddin, who is said to be the progenitor of all the Christian families that founded the city. The story goes that “Rashid Al-Hadaddin fled from Al-Karak (in present-day Jordan) in the middle of the 16th century after a disagreement with a Muslim family there. He led his small caravan across the barren hills of Jordan to a forested area 16 kilometers north of Al-Quds and, between the caves and remnants of Roman villages, the caravan settled and built their new home.”

The oral tradition indicates that Rashed Al-Hadaddin later returned to Al-Karak, but his five sons were determined to stay in Ramallah and so became the grandfathers of its people and the namesakes of its lions.

Al-Manara roundabout is at the meeting point of six roads, the foremost amongst them being Rukkab Street, named after the famous ice cream parlor, known for selling the tastiest ice cream in Palestine.

As Al-Manara is the destination of many roads, so Ramallah seems to be the destination of many people new to the country. Travelers come first to Ramallah and rest here, before exploring further. As one folk song puts it: “Where to? Ramallah! Tell me traveler, where to? Ramallah! Do you not fear Allah, tell me traveler, where to? Ramallah!”

Among such travelers was Palestine’s most famous literary son, the poet Mahmoud Darwish. Returning from his exile, he settled in the Al-Teerah district and worked in the Khalil Sakakkini Cultural Centre in the Masyoun district. On Ramallah’s streets, you might also catch a glimpse of other writers who have returned, like the poet and novelist Zakaria Mohammed who, after 25 years of exile in Tunisia, returned. You might see him walking on Maktaba Street, for example, or heading down to Ramallah Al-Tahta where you can find street vendors selling falafel, hummus and grilled meat. There you might also bump into the short story writer Ziad Khadash sitting with a group of writers in the Insheraah Coffee Shop or the Ramallah Coffee Shop. If you’re lucky you’ll see the serene figure of lawyer and author Raja Shehadeh, passing through the streets with such gentle politeness you would hardly even know he was there. Or perhaps you will catch sight of architect and author Suad Amiry on her way to the Riwaaq Centre for Architectural Conservation, or Salim Tamari on his way to the Institute for Palestine Studies. There are authors on every street, this being a city teeming with culture where not just writers and artists have made their home, but also arts organizations. Here you will find the Abdel Mohsen Qattan Foundation, the Al-Qasabah, the Al-Sareyah, the Cooperation Institute, the Palestine Writing Workshop, the Tamer Institute for Community Education and nearby in Birzeit is the Palestinian Museum and Birzeit University.

This is Ramallah for you: a horizontal city—ranged along the contours of a hilltop ridge, where so much is new—surrounded by much more vertical cities, whose topography tips over the sides of steep, vertiginous valleys, or gathers around mountain tops, cities deep with history.

It is a city of contrasts, with a sophisticated café culture and modern restaurants as well as working-class falafel shops and markets. A city of businessmen and NGO staffers, modern companies and haphazard buildings that almost obliterate the historic limestone houses hidden among them, with their ancient, subtle architecture whose original families have since been lost to the diaspora. It is a city with three refugee camps in its center: Al-Am’ari, Al-Jalazon and Qalandia. A city of deprivation and neglect, not to mention continuous raids, demolitions and arrests by the IDF.

It is the city that is always testing how far it can go, experimenting with what’s possible, and being judged in the process.People commute from the towns and villages to the north and south for work, many of them living in Ramallah during the week and only returning to their homes at the weekend. So come Thursday night the place changes, almost becomes a ghost town compared to the hustle and bustle of mid-week. Ramallah is also home to many foreign NGO employees who add a different vibe and way of life and also add a premium to the price of everything. So the city has a new class of middle-income workers struggling to pay off loans for luxury cars and other consumer products.

Ramallah is also a city of aspiring pop groups, hip-hop producers and experimental musicians who you might see perform at venues such as The Garage or Radio or Al-Muhatta or Shams. It’s a city of performance artists, theatre producers, filmmakers and actors, many of whom can be found in cafés like Zamaan and Al-Inshiraah. Because of all of this, it is also the city that is always testing how far it can go, experimenting with what’s possible, and being judged in the process.

__________________________________

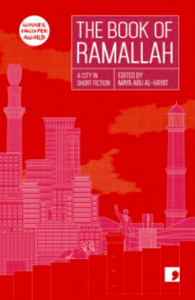

Excerpted from The Book of Ramallah, ed. by Maya Abu Al-Hayat, Comma Press, 2021.

Previous Article

Café Life and Literati: Life in Turn-of-the-Century PragueNext Article

75 Nonfiction Books You ShouldRead This Summer