Life and Death in the Impoverished Neighborhood of Alabama Village

“A commemoration to the dead, a warning to the living.”

For a short time, a photograph of Tony “TJ” Brisker hung alone above a white wood door at Light of the Village, a church in Alabama Village, a destitute neighborhood in the Mobile suburb of Prichard in southern Alabama.

Other young men in the neighborhood had died violently before him; more than a few had combustible tempers, sold drugs, and toted guns, but they had mothers and fathers and siblings and in some instances children, and their families and friends missed them.

The founders of the church, John and Dolores Eads, felt each passing. They had known almost all of them as children and although they did not condone many of their choices, they also believed that drug dealing did not define the entire person. They spoke at their funerals and mourned their absence. Because of how they lived, their deaths, although tragic, did not shock them.

The idea that someone would shoot him made no sense. Everyone liked him.

TJ’s death, however, did.

Since they began their ministry in 2002 in an abandoned crack house on Baldwin Drive in Alabama Village, John and Dolores had never seen TJ raise his voice in anger. Not once.

He didn’t carry a weapon, and he never had an altercation with the police that they knew of—or with anyone else. The idea that someone would shoot him made no sense. Everyone liked him.

He was thirty years old and stood six feet, three inches tall. He had broad shoulders and neatly cut thick, pitch-black hair. He maintained a tightly trimmed goatee and looked out at the world with an inscrutable gaze. He dressed casually in T-shirts of all colors and blue jeans. A jacket when the weather turned cold. Big TJ, the young people called him. He had seen his father shot and killed in a Mobile housing project when he was about fifteen. He rarely spoke about that or anything else. John and Dolores heard him say maybe six words in the years they had known him, in a voice whose pitch was higher than might be expected from a man of his size.

What up TJ?

Mmmm, he’d respond if he said anything at all.

He wandered around the Village like nothing else mattered, stopping at the church to shoot baskets on a court behind it. When guys got together for a game, TJ would join them without asking, without a word of any kind, and no one challenged him. He didn’t dribble the ball or do any fancy footwork. He rarely moved at all. He preferred instead to stand in one spot swaying from side to side and watching the other players. The sun would beat down, sweat would wax his arms, and he would barely blink. He rocked back and forth as if listening to something beyond the hearing of the other players.

They all knew not to leave him open because if he caught the ball he would score. Gripping the ball in his big hands, bent at the knees, his eyes narrowed, he would jump, releasing the ball in one fluid motion, his arms remaining in the air like a conductor until the ball whooshed through the net. He didn’t run a victory lap or pump his arms or shout. He would stand motionless and solemn and begin swaying again, waiting to snag the ball. He never remarked upon his skill. If he couldn’t make a shot, he passed the ball, but that rarely happened. TJ scored.

A small, shaggy, black terrier mutt followed him. Whether it was his dog or a dog that adopted him no one knew. He never spoke to the dog or called it by name, but they communicated in their way, the dog patiently staring at him, alert to the unspoken messages that passed between them. They were a pair, and the dog sat and waited for him when he went inside the church to ask for a basketball.

Some people described TJ as simple. Other people presumed he was mentally retarded. John and Dolores never accepted such characterizations. They thought TJ was content, a man who took pleasure in his own company and that of his dog and expected or needed little in return.

John and Dolores may have been one of the last friendly faces TJ saw before he died on a dank, drizzly December evening in 2011.

He couldn’t read, so Dolores set him up with a CD player and he listened to recordings of the Bible. Sometimes he would sit inside the church at a cubicle or outside at a picnic table under the shade of a tree, interrupted from time to time by falling acorns. He listened to the recordings at the basketball court while other young men played.

On Sundays, he would attend John’s Bible study classes. He never asked questions or indicated if he had a favorite Gospel. When Dolores saw him, she would ask, Do you want to listen to the Bible? Yes, TJ would respond in that high, quiet voice of his, or if he saw her first he would say, Can I listen? and Dolores would give him the CD player with the Bible audiobook.

John and Dolores may have been one of the last friendly faces TJ saw before he died on a dank, drizzly December evening in 2011. They had been driving a white van filled with twenty bags of Christmas gifts for Village families. The head- lights on low to cut through a dense, gray mist. The roads slick and wet. The van bumped over asphalt shattered by tree roots, almost impassable from decay and neglect. Wipers thumping back and forth. Dim illumination from the shuttered houses, weighted by weather, did little to beat back the gloom.

About six young men whom John recognized sprawled on the warped porch of TJ’s home, a pale green house on Chilton Street not far from the church. A sagging strand of white Christmas lights framed the door. Recognizing John, the young men moved aside as he mounted the steps.

Hey, Mr. John, they said. He stood before them holding a bag with a new pair of white sneakers and a box of chocolate cookies and asked for TJ. He’s inside, they told him. John raised a fist and knocked on the door. He’d had a long day. The weather sucked. He had seventeen more presents to deliver. He wanted to finish this and drive home to Bay Minette about thirty miles away.

Just go inside, one of the young men told him.

John opened the door. Blue light from a TV illuminated the interior. Rumpled blankets on a living room couch suggested someone had used it as a bed. Dishes and glasses and foam food containers cluttered the kitchen counter. TJ emerged from the depths of a back hall.

Hey, we got gifts for you, John said.

He gave TJ the bag.

Check this out, TJ.

TJ cleared counter space for the cookies, withdrew the shoebox from the bag and looked inside.

Thanks, he said after a moment with no inflection to his voice, but John thought he was pleased.

This is great, TJ said.

Merry Christmas, TJ, John said.

Merry Christmas.

We’ll see you Sunday.

Yeah, I’ll be there.

TJ saw him to the door. John hurried out, wished the guys on the stoop a Merry Christmas. You too, Mr. John, they said as he got into the van. One down, sixteen more to go. The chilly night penetrated his coat and made him shiver. He turned up the heat. He and Dolores completed two more deliveries when he received a call from Key Key, the daughter of Betty Catlin, a church employee.

Hey did you hear? Key Key said. Hear what? John asked.

TJ. He died.

No! I just saw him.

Yes, he did too. I just got a call.

Are you sure?

He got shot, Mr. John.

John spun the van around and raced back to TJ’s house. Yellow police tape cordoned off Chilton Street, snapping and wavering, and the rotating red lights from the roofs of squad cars bruised the surrounding homes and the faces of the gathered men and women, their voices hushed, curious. An ambulance had already taken TJ to Southern Alabama Medical Center in Mobile.

He should have given him more time. Maybe he was depressed. Maybe he needed him and in his hurry John had not been sensitive enough to notice.

When John and Dolores got there, he was in the ICU, brain-dead but on life support for organ donation. Eyes closed, a bloody bandage around his head. A tube in his mouth. Machines beeping, bright lights reflecting off a white tile floor and ceiling. John said a prayer, God be with TJ now and give him peace. His mother, whom John had met before but didn’t know well, thanked him for coming. She told him TJ had shot himself. He was depressed, she said in a flat voice that revealed no emotion but John saw the pain in her sunken eyes.

He refused to believe TJ had died by suicide. He had not seemed unhappy when he saw him. John knew the young men on the porch carried guns. He thought it was more likely one of them had been playing with a pistol and killed TJ by accident. He couldn’t imagine anyone shooting him on purpose. He couldn’t imagine TJ doing it to himself.

He enjoyed going to the church, his mother said.

In the following days, TJ’s death lingered in John’s thoughts, a disturbing presence. He had been in a rush to deliver all of the Christmas gifts. He had left TJ’s house too soon. He should have given him more time. Maybe he was depressed. Maybe he needed him and in his hurry John had not been sensitive enough to notice.

He scolded himself: I was one of the last people he saw and all I could say was, Merry Christmas, see you Sunday, because I wanted to get home. He thought of how TJ enjoyed listening to the Bible. In his own way, he had been talking to God up until he died. This thought didn’t deaden the pain of his death or of John’s self-recrimination. However, it gave him perspective and a dose of humility. This wasn’t about what he should or should not have done. It wasn’t about him at all. It was about TJ. He had not died alone but in the comfort of his faith.

The photographs will remain as long as the church exists. A commemoration to the dead, a warning to the living.

Still, John thought, he should try to be a little more aware. The fragility of life in the Village meant that those he saw one day he might not see the next.

The photo John and Dolores picked to commemorate TJ showed him on a sunny day standing with boys who participated in recreational activities at the church. They were gathered before a blue-and-green mural with its white, puffy clouds and a black crucifix suspended in the sky with the declaration Jesus Is The Way below it. A few of the boys smiled. Others crossed their arms and flashed gang signs. TJ wore a white T-shirt. His hair caught the sun; his head was cocked a little to one side.

John and Dolores hung the picture without ceremony. For anyone who asked about it, they explained that at one time a man named TJ had come to the church accompanied by a small black dog and listened to the Bible and played basketball. He lived in the memories of those who knew him and also, John and Dolores believed, in heaven.

In the years that followed TJ’s death, weeds, trees, and brush consumed Chilton Street, and many more young people died. The rising death count influenced John and Dolores to establish a memorial. TJ’s photo and dozens of more pictures of mostly young black men who at one time had participated in the church now take up a wall. The majority of them, like TJ, were shot. The families of the deceased tape photographs of their loved one on the wall and John says a prayer. The photographs will remain as long as the church exists. A commemoration to the dead, a warning to the living.

__________________________________

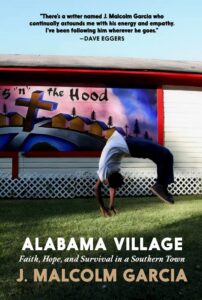

From Alabama Village: Faith, Hope, and Survival in a Southern Town. Used with the permission of the publisher, Seven Stories Press, distributed by Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2025 by J. Malcolm Garcia.

J. Malcolm Garcia

J. Malcolm Garcia was born in the Chicago suburb of Winnetka, IL. He attended Ripon College from 1975 to 1977. He transferred to Coe College in the fall of 1977 and graduated from Coe in May 1979. He wrote for The Coe Cosmos newspaper and was active in college theater. As a social worker, Garcia worked with homeless people in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district for 14 years before he made the jump into journalism in 1997. He reported for The Kansas City Star newspaper from 1998 to 2009 when he began his freelance career. The tragedy of September 11th, 2001, gave him the opportunity to work in Afghanistan. Since then he has written on Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Chad, Haiti, Honduras, and Argentina among other countries. He is a recipient of the Studs Terkel Prize for writing about the working classes and the Sigma Delta Chi Award for excellence in journalism.