Life Advice From Adrienne Rich

On the 5th Anniversary of her Death

Today marks five years since the death of Adrienne Rich, the incredible poet, essayist and feminist activist. I’ve been thinking about Rich a lot lately; so much of what she has written feels even more urgent and necessary than ever, especially as the creative community grapples with the sudden change in what it feels like to make Art in our new, ugly America. Of course, much has not changed, but merely been brought to our attention—but Rich herself was almost never fooled in this way.

To give just one example, in 1997, Rich refused the National Medal for the Arts, writing to President Bill Clinton (actually writing to a woman, Jane Alexander—then-Chairperson of the National Endowment for the Arts—and cc’ing Bill Clinton) that she could not accept such an award “because the very meaning of art, as I understand it, is incompatible with the cynical politics of this administration. … There is no simple formula for the relationship of art to justice. But I do know that art—in my own case the art of poetry—means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of power which holds it hostage. The radical disparities of wealth and power in America are widening at a devastating rate. A President cannot meaningfully honor certain token artists while the people at large are so dishonored.”

To which I can only say, god damn, was she ever the greatest. I think we should all try to be more like Adrienne Rich, and to that end, I’ve compiled some of her thoughts on how best to live below. Read, enjoy, and perhaps seek, in the following days, to live a little bit more actively.

On taking responsibility towards yourself:

I want to suggest that there is a more essential experience that you owe yourselves, one which courses in women’s studies can greatly enrich, but which finally depends on you in all your interactions with yourself and your world. This is the experience of taking responsibility toward yourselves. Our upbringing as women has so often told us that this should come second to our relationships and responsibilities to other people. We have been offered ethical models of the self-denying wife and mother; intellectual models of the brilliant but slapdash dilettante who never commits herself to anything the whole way, or the intelligent woman who denies her intelligence in order to seem more “feminine,” or who sits in passive silence even when she disagrees inwardly with everything that is being said around her.

Responsibility to yourself means refusing to let others do your thinking, talking, and naming for you; it means learning to respect and use your own brains and instincts; hence, grappling with hard work. It means that you do not treat your body as a commodity with which to purchase superficial intimacy or economic security; for our bodies to be treated as objects, our minds are in mortal danger. It means insisting that those to whom you give your friendship and love are able to respect your mind. It means being able to say, with Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre: “I have an inward treasure born with me, which can keep me alive if all the extraneous delights should be withheld or offered only at a price I cannot afford to give.”

Responsibility to yourself means that you don’t fall for shallow and easy solutions—predigested books and ideas, weekend encounters guaranteed to change your life, taking “gut” courses instead of ones you know will challenge you, bluffing at school and life instead of doing solid work, marrying early as an escape from real decisions, getting pregnant as an evasion of already existing problems. It means that you refuse to sell your talents and aspirations short, simply to avoid conflict and confrontation. And this, in turn, means resisting the forces in society which say that women should be nice, play safe, have low professional expectations, drown in love and forget about work, live through others, and stay in the places assigned to us. It means that we insist on a life of meaningful work, insist that work be as meaningful as love and friendship in our lives. It means, therefore, the courage to be “different”; not to be continuously available to others when we need time for ourselves and our work; to be able to demand of others—parents, friends, roommates, teachers, lovers, husbands, children—that they respect our sense of purpose and our integrity as persons.

…

The difference between a life lived actively, and a life of passive drifting and dispersal of energies, is an immense difference. Once we begin to feel committed to our lives, responsible to ourselves, we can never again be satisfied with the old, passive way.

(From “Claiming an Education,” a speech Rich delivered to the graduating class of Douglass College in 1977, which was eventually reprinted in On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose 1966–1978)

On the truth about truth:

To lie habitually, as a way of life, is to lose contact with the unconscious. It is like taking sleeping pills, which confer sleep but blot out dreaming. The unconscious wants truth. It ceases to speak to those who want something else more than truth.

In speaking of lies, we come inevitably to the subject of truth. There is nothing simple or easy about this idea. There is no “the truth,” “a truth”—truth is not one thing, or even a system. It is an increasing complexity. The pattern of the carpet is a surface. When we look closely, or when we become weavers, we learn of the tiny multiple threads unseen in the overall pattern, the knots on the underside of the carpet.

This is why the effort to speak honestly is so important. Lies are usually attempts to make everything simpler—for the liar—than it really is, or ought to be.

In lying to others we end up lying to ourselves. We deny the importance of an event, or a person, and thus deprive ourselves of a part of our lives. Or we use one piece of the past or present to screen out another. Thus we lose faith even with our own lives.

The unconscious wants truth, as the body does. The complexity and fecundity of dreams come from the complexity and fecundity of the unconscious struggling to fulfill that desire. The complexity and fecundity of poetry come from the same struggle.

(From “Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying,” first read at the Hartwick Women Writers’ Workshop in June of 1975 and eventually reprinted in On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose 1966–1978)

On the importance of love:

An honorable human relationship—that is, one in which two people have the right to use the word “love”—is a process, delicate, violent, often terrifying to both persons involved, a process of refining the truths they can tell each other.

It is important to do this because it breaks down human self-delusion and isolation.

It is important to do this because in doing so we do justice to our own complexity.

It is important to do this because we can count on so few people to go that hard way with us.

(From “Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying,” first read at the Hartwick Women Writers’ Workshop in June of 1975 and eventually reprinted in On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose 1966–1978)

On living with the female body:

In order to live a fully human life we require not only control of our bodies (though control is a prerequisite); we must touch the unity and resonance of our physicality, our bond with the natural order, the corporeal grounds of our intelligence.”

(From Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution)

On how to help:

If you are trying to transform a brutalized society into one where people can live in dignity and hope, you begin with the empowering of the most powerless. You build from the ground up.You begin by stopping the torture and killing of the unprotected, by feeding the hungry so that they have the energy to think about what they want beyond food. … Food, health, literacy, like free contraception and abortion, are basic feminist issues.

(From “‘Going There’ and Being Here,” (1983), published in Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose 1979-1985)

On the obligations of the poet:

I don’t know that poetry itself has any universal or unique obligations. It’s a great ongoing human activity of making, over different times, under different circumstances. For a poet, in this time we call “ours,” in this whirlpool of disinformation and manufactured distraction? Not to fake it, not to practice a false innocence, not pull the shades down on what’s happening next door or across town. Not to settle for shallow formulas or lazy nihilism or stifling self-reference.

Nothing “obliges” us to behave as honorable human beings except each others’ possible examples of honesty and generosity and courage and lucidity, suggesting a greater social compact.

(From a 2011 interview with The Paris Review)

On community:

No person, trying to take responsibility for her or his identity, should have to be so alone. There must be those among whom we can sit down and weep, and still be counted as warriors.

(From Sources)

On requirements for the creative life:

The serious revolutionary, like the serious artist, can’t afford to lead a sentimental or self-deceiving life. Patience, open eyes, and critical imagination are required of both kinds of creativity.

(From “Three Classics for New Readers” in A Human Eye: Essays on Art in Society, 1996-2008

On what makes relationships worth having:

Truthfulness, honor, is not something which springs ablaze of itself; it has to be created between people.

This is true in political situations. The quality and depth of the politics evolving from a group depends in large part on their understanding of honor.

Much of what is narrowly termed “politics” seems to rest on a longing for certainty even at the cost of honesty, for an analysis which, once given, need not be re-examined. …Truthfulness anywhere means a heightened complexity. But it is a movement into evolution. Women are only beginning to uncover our own truths; many of us would be grateful for some rest in that struggle, would be glad just to lie down with the sherds we have painfully unearthed, and be satisfied with those. Often I feel this like an exhaustion in my own body.

The politics worth having, the relationships worth having, demand that we delve deeper.

(From “Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying,” first read at the Hartwick Women Writers’ Workshop in June of 1975 and eventually reprinted in On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose 1966–1978)

On reading and writing:

You must write, and read, as if your life depended on it. That is not generally taught in school. At most as if your livelihood depended on it: the next step, the next job, grant, scholarship, professional advancement fame; no questions asked as to further meanings. And let’s face it, the lesson of the schools for a vast number of children—hence, of readers—is This is not for you.

To read as if your life depended on it would mean to let into your reading your beliefs, the swirl of your dreamlife, the physical sensations of your ordinary carnal life; and simultaneously, to allow what you’re reading to pierce routines, safe and impermeable, in which ordinary carnal life is tracked, charted, channeled. Then, what of the right answers, the so-called multiple-choice examination sheet with the number 2 pencil to mark one choice and one choice only?

To write as if your life depended on it: to write across the chalkboard, putting up there in public words you have dredged, sieved up from dreams, from behind screen memories, out of silence—words you have dreaded and needed in order to know you exist. No, it’s too much; you could be laughed out of school, set upon in the schoolyard, they would wait for you after school, they could expel you. The politics of the schoolyard, the power of the gang.

Or, they could ignore you.

(From What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics)

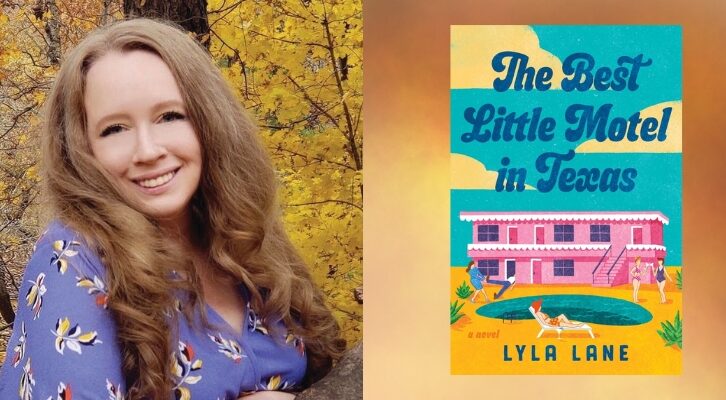

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.