Liberty or Death: On the Prophetic Visions and Unflinching Will of

Harriet Tubman

Dorothy Wickenden Recounts the Early Life of an American Hero

Harriet Tubman had several stories to tell about her childhood, all with one stark message: this is how it was to be enslaved, and here is what I did about it. She did not know the year of her birth, let alone the month or day—only that she was the fifth of nine children, and that she was born in the early 1820s. Her parents, Ben and Harriet Ross, named her Araminta, and as a child she was called Minty.

Almost two centuries later, a scholar unearthed her birthday—March 15, 1822—by piecing together a notation in a slaveholder’s ledger, a legal dispute about who owned her, and an October 1849 advertisement in a newspaper on Maryland’s Eastern Shore for a 27-year-old runaway slave. When Tubman was in her eighties, she told a friend in Auburn that her first memory was of lying in a cradle made from the trunk of a sweet gum tree: “You seen these trees that are hollow. Take a big tree, cut it down, put a bode in each end, make a cradle of it and call it a ’gum. I remember lying in that there, when the young ladies in the big house where my mother worked, come down, catch me up in the air before I could walk.”

Harriet couldn’t remember her oldest sister, who was sold when she was three years old. Two other sisters had been leased away by their enslaver, as her mother, who went by the name of Rit, pleaded for mercy. In a recurring nightmare, Harriet heard the thud of horses’ hooves and the shrieks of women as men rode in and tore children out of their mothers’ arms. Rit’s owner was an impecunious farmer named Edward Brodess.

When Rit learned that Brodess intended to sell her son Moses, she hid him in the swamp behind the cabin. Brodess spent a month trying to find him, finally sending over a neighbor with the pretext of needing a light for his cigar. Rit told the neighbor, “You are after my son, but the first man that comes into my house, I will split his head open.” Tubman later took Rit’s full name, Harriet, as her own—a tribute to the woman who showed her that it was possible for a slave to resist a slaver.

Rit and her children lived on Brodess’s 200-acre farm, 80 miles east of Washington, across the Chesapeake Bay, amid the tidewaters and marshes, the fields and forests of Dorchester County, in a hamlet called Bucktown, marked by nothing more than a Methodist church and a dry goods store. Tubman’s father, Ben Ross, was owned by Anthony Thompson, a plantation owner ten miles away. Tubman and her siblings belonged to Brodess: by law, if a mother was enslaved, so were her children. Rit worked in Brodess’s house, but Harriet was put to work very young in the fields—corn, wheat, and rye.

The landscape of the Eastern Shore was flat and bleak all winter, with little delineation between earth, sky, and water except for the tall trunks and high green canopies of loblolly pines. In the springtime, white visitors exclaimed over the scents of honeysuckle and spicebush and at the pink and white blossoms of the fruit trees. Harriet had an expedient view of the natural world. Rabbits, waterfowl, and fish could be surreptitiously trapped and eaten, and ripe apples plucked from the orchards; the forest, the swamp, and the shore grasses provided lifesaving hiding places; and on a clear night the North Star was a beacon to a better place.

Maryland’s population was an unusual mix of free and enslaved people: 418,000 whites, 90,000 slaves, and 75,000 free Blacks. Its planters believed they were more benevolent than the large plantation owners in the Deep South, but they didn’t think twice about selling off a child or a parent if they needed money.

On Sundays and holidays, they permitted slaves to visit family members on other farms; and they condoned marriages between slaves and free Blacks because it reduced the risk of flight, and because the children of enslaved mothers provided the next generation of unpaid labor. In rural counties, when the fields were fallow, slaveholders generated cash and saved on the cost of food by hiring out their human property, usually allowing them to save a portion of what they earned. Over many years, some enslaved people were thus able to buy their freedom.

Harriet recalled that Brodess first sent her away at the age of six or seven, to work for a planter named James Cook and his wife. It was winter, trapping season for muskrats, and Cook ordered her into the marshes to check his traps. She slept on the floor by the fireplace, crying for her mother. At the age of nine, Harriet found herself working for another family, answering to a vicious woman she called Miss Susan. She had never performed the duties of a maid. Miss Susan ordered her to move the parlor chairs and tables into the middle of the room, sweep the carpet, dust everything, and return the furniture. She did as she was told, dusting until she could see her face in the shining surfaces, then set the table, and went to do her other chores.

Tubman later took Rit’s full name, Harriet, as her own—a tribute to the woman who showed her that it was possible for a slave to resist a slaver.

A little while later, Miss Susan called her back. A whip in one hand, she ran a finger of the other through a film of dust that had settled on the table and piano. She thrashed Harriet on her neck and shoulders, then told her to do the cleaning again. The excruciating sequence of work and punishment was repeated four times until Miss Susan’s sister, unable to bear the child’s screams, came in, said she’d take care of it, and told Harriet that after sweeping, she must allow some time for the dust to gather, and then do her dusting.

At night, Miss Susan ordered Harriet to watch her sick, fretful baby. She kept her whip within reach as she slept, and if she woke to the baby’s cries and saw that Harriet had dropped off to sleep, she beat her again. The scars, emotional and physical, were permanent. Still, she was luckier than some. In a case in the next county, which caused a stir even among people mostly inured to the savageries of slavery, the mistress of a girl of 15 or 16 who fell asleep while tending the woman’s baby picked up a heavy stick from the fireplace, beat the girl on her head and breastbone, and left her to die. Criminal laws in such cases were rarely enforced. Harriet’s most grievous injury occurred sometime after working for Miss Susan, when she was hired out to a man named Thomas Barnett and his wife, a prizewinning weaver.

While breaking flax in a field outside Bucktown, she was ordered to pick up some supplies at the dry goods store. Before setting off, she put a shawl over her hair, which had never been combed. It “stood out like a bushel basket,” she said, “and when I’d get through eating I’d wipe the grease off my fingers on my hair.” At the store, Barnett’s overseer ordered Harriet to restrain an enslaved man who was there without permission. She refused, and the overseer took a two-pound iron scale weight from the counter, hurling it at the man, but it fell short and hit Harriet instead. She recalled, “The weight broke my skull and cut a piece of that shawl clean off and drove it into my head. And I expect that hair saved my life.”

They carried her to the house, bleeding and fainting. “I had no bed, no place to lie down on at all, and they lay me on the seat of the loom, and I stayed there all that day and next.” Then she was sent back to the fields, “and there I worked with the blood and sweat rolling down my face til I couldn’t see.” Weak and injured, she wasn’t much use, and she was returned to Brodess. He hired her out to a neighbor who had her clean the house, milk the cows, and take care of the children. That neighbor, too, sent her back to Brodess, complaining, “She don’t worth the salt that seasons her grub.”

Tubman said that Brodess attempted to sell her, but “They wouldn’t give a sixpence for me.” As an adult, she suffered from agonizing headaches and seizures, dropping off to sleep mid-sentence; her left eye drooped and she had a scar on her temple—all legacies of the iron weight. The trouble in her head, as she called it, prevented her from learning to read and write, and it gave rise to visions that she considered prophetic.

Despite this handicap and a height of barely five feet, Tubman became known for feats of strength. In the late 1830s, a wealthy farmer and shipbuilder named Joseph Stewart hired her out from Brodess. She worked for Stewart for several years, and as an adult she boasted that she did all the work of a man—driving oxen, carting, and plowing. She could cut half a cord of wood a day, lift barrels, and pull boats loaded with goods through a canal in Parsons Creek funded by Stewart, Thompson, and other landowners, and built by slaves and freedmen. Tubman said, “I was getting fitted for the work the Lord was getting ready for me.”

Harriet’s father, Ben, was freed in 1840, by Anthony Thompson’s son, Dr. Anthony C. Thompson. Several years later, the younger Thompson began to acquire a 2,000-acre timber plantation at Poplar Neck, in Caroline County, 25 miles northeast of Bucktown, and he hired Ben as his foreman. Ben was a skilled carpenter who knew all of the local hardwoods—sweet gum, white oak, maple, birch, mahogany, cedar, locust, loblolly pine. He could look at a tree and gauge how many logs it would yield, and see from its curving limbs whether it would be suited for building a ship’s hull or keel.

Thompson Jr. sometimes hired Rit and her children to work for him, and Harriet was allowed to keep an allotment of the 50 or 60 dollars that she earned for her labor. People were often illegally enslaved, and Harriet, suspecting that her mother’s original owner had made provisions in his will for releasing his slaves after his death, paid a lawyer five dollars to investigate Brodess’s claim to Rit. Such inquiries were common enough that one slaveholder complained that slaves employed white lawyers to “pry into every man’s title to his negroes.”

Harriet’s hunch was right. Brodess’s great-grandfather had stipulated that the women and children he owned be freed once each turned 45 years old. Rit should have been released around 1830, more than a decade earlier. Instead, she and her sons and daughters had been passed along in turn to three other family members, until Brodess assumed ownership. The Brodess clan was tied up in decades-long litigation, and Harriet’s discovery did not result in freedom for her, Rit, or her siblings. It only hardened her hatred of the Brodesses and her determination to break away.

Brodess saw Ben and Rit as hard, loyal workers, but they were agents on the local branch of the underground railroad, hiding slaves and advising them about the best means of escape. Harriet paid close attention to her parents’ acts of sabotage. Bewildered slavers of the Eastern Shore knew that abolitionists helped slaves vanish, but they couldn’t fathom how. As one said, they concealed people “in a labyrinth that has no clue.”

Ben and Rit, familiar with the Delmarva Peninsula’s many escape routes by land and water, also knew which white families provided shelter, and advised freedom seekers how to evade bounty hunters and bloodhounds. Harriet became familiar with the tides and learned how to find fresh water, and she interrogated free Blacks about the coded body language and personal networks that made escape possible. Men who drove oxen and cut logs knew wharf workers, who knew ship hands, called black jacks, on the boats heading north. By her early twenties, Harriet was starting to assemble a map in her mind, memorizing the safest routes to Delaware and Pennsylvania.

In about 1844, at age 22, Harriet married John Tubman, a free man who worked as a general laborer. Four years later, she started plotting her escape. There were persistent rumors that Brodess, who was again in debt, intended to sell off more slaves. Harriet spoke to God, she said, “as a man talketh with his friend,” and she began praying that Brodess would repent: “I groaned and prayed for old master: ‘Oh Lord, convert master! Oh Lord, change that man’s heart!’”

Brodess began to bring around potential buyers, and when Tubman heard that she and her brothers Henry and Ben would be joining a chain gang headed for the cotton and rice fields of the Deep South, she prayed: “Oh Lord, if you ain’t never going to change that man’s heart, kill him, Lord, and take him out of the way.” Six days later, Brodess died at the age of 47, bequeathing Rit and her grown children to his widow, Eliza. Harriet, sure that Eliza would go through with the sale, decided to flee with her brothers.

The trouble in her head, as she called it, prevented her from learning to read and write, and it gave rise to visions that she considered prophetic.

Bereft at leaving her parents and her other siblings, she assumed that her husband would be with her. But John Tubman was a stolid man with steady work who had no desire to take his chances elsewhere. Free people caught escaping with fugitive slaves were liable to be sold into slavery, shot in the back, or torn apart by bloodhounds. John mocked Harriet for the credence she gave to her dreams and visions. In one of them, she saw a line dividing South from North, “and on the other side of that line were green fields, and lovely flowers, and beautiful white ladies who stretched out their arms to me over the line.”

Her destination was Philadelphia, a city known to have paying jobs for Black people and schools for their children, where white and Black anti-slavery friends shared meals at each other’s homes, attended abolitionist meetings, and helped lost souls start again. Harriet dismissed John’s warnings, confident that she would find work and a place to live, and that when she came back for him, he would join her.

On the night of September 17, 1849, Harriet, Henry, and Ben started on their journey from Anthony Thompson Jr.’s property in Poplar Neck, where their parents were living. The plantation was just a mile from an old Quaker settlement, the Marshy Creek Friends of the Northwest Fork Meeting, where two Friends, Jacob Leverton and his wife, Hannah, were trusted contacts of Ben and Rit.

The Levertons’ home was a busy underground railroad depot for freedom seekers moving through the area. The Levertons fed, clothed, and directed people, some of them bloodied from a recent beating, “onwards toward the North Star.” Familiar with Patrick Henry’s famous words, Harriet later said, “I started with this idea in my head, ‘There’s two things I’ve got a right to, and these are, Death or Liberty—one or t’other I mean to have. No one will take me back alive; I shall fight for my liberty, and when the time has come for me to go, the Lord will let them kill me.’”

Eliza Brodess placed an advertisement in the local paper, The Cambridge Democrat, describing Henry as 19, Ben as about 25, and “Minty” as “a chestnut color, fine-looking, and about five feet high.” She offered 100 dollars for each if captured out of state; 50 if taken in state. As they got under way, Henry and Ben had second thoughts. More terrified of capture than of their punishment on a voluntary return, they refused to continue. Not sure they could make it safely on their own, Harriet returned with them. The following night, after one of Thompson Jr.’s slaves told her that she was to be sold immediately, she prepared to leave again, this time alone.

__________________________________

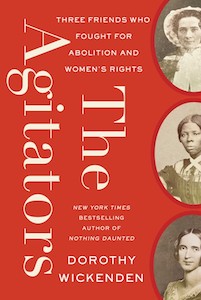

Excerpted from The Agitators: Three Friends Who Fought for Abolition and Women’s Rights. Used with the permission of the publisher, Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Dorothy Wickenden.

Dorothy Wickenden

Dorothy Wickenden is the author of Nothing Daunted and The Agitators, and has been the executive editor of The New Yorker since January 1996. She also writes for the magazine and is the moderator of its weekly podcast The Political Scene. A former Nieman Fellow at Harvard, Wickenden was national affairs editor at Newsweek from 1993-1995, and before that was the longtime executive editor at The New Republic. She lives with her husband in Westchester, New York.