Letter to My Child: Cathy Park Hong on the Peculiar Rhythms of Life During Quarantine

Remembering the Summer of 2020

Dear Meret,

I want to capture a season for you, the summer of 2020 during the pandemic, when we escaped the city and lived as if the virus furred the edges of each day’s film strip but never tore the day in half. We are surrounded by trees that I cannot name that surround our deck. One maple has been sundered by lightning and slopes to the left, offering a pleasing asymmetrical composition to a painter if she were to paint our backyard. The greenery of Vermont turns theatrical as the day wanes where the last strains of sun slit through the branches, turning our copse of oak into a cathedral of light. A wood thrush in the trees sings several ethereal notes to the faint, coppery chorus of crickets that curtains the forest. We hear shots, target practice for the fall, when the air will crisp and woodland creatures will be skinned and dressed, which scare the neighbor’s white Pomeranian into fleeing their home for the woods, never to be seen again.

When you’re not at camp, we head to the local pond. I swim when you’re at camp, too. I search restlessly for the perfect spring-fed pond, a body of water that is clear and silvery and not fretted with the roots of lily pads or a map of algae scum. Your father doesn’t want me to tell you that I’ve been sneaking into a pond that has closed for the season because of the pandemic. There is no barrier except for a gate that I can easily climb under. It is a man-made pond, ninety feet deep, used during the winter to churn out snow for the nearby ski slopes. From the aerial view of a drone, the pond is an eye, cleared of trees. When I swim, I never wear goggles because I don’t want to see what is beneath me, just a hazy blue galaxy where I only see my thoughts. Sometimes there are other trespassers jogging or walking their dogs around the pond, all of whom, except for me, are White.

Darkness, your father is gathering wood to make a bonfire. You are climbing the pyramid of chopped wood, shouting that we will all toast marshmallows for s’mores. I become irrationally annoyed when your father begins to gather the wood to cultivate a fire, perhaps because I am pulled from the safety of the deck into the dark meadow, where I am attacked by bugs. You run up to me and beg to eat three s’mores, to which I assent, but then you demand that I go to the kitchen and deliver the marshmallows, which is your habit: to follow a met demand with a bigger demand. If that is what you want, I say, you bring down the marshmallows. I stay on the deck. Maybe I dislike bonfires because it reminds me of forced gatherings where we are required to sing songs. There are two friends visiting us from the city with proof they have recently tested for the virus. They migrate slowly towards the fire. Earlier that day, they had surrounded you like supplicants from a Baroque painting, each one of them taking turns trying to pluck a splinter from your toe that, in the end, refused to give. Now you dance among them around the fire, handing each one a sparkler.

I want to capture a season for you, the summer of 2020 during the pandemic, when we escaped the city and lived as if the virus furred the edges of each day’s film strip but never tore the day in half.The next month, another family with twin boys arrives from the city, with proof that they too have tested negative. A tent sprouts up like a mushroom in our backyard. The boys, who are seven, seem permanently spooked by the virus, afraid of anyone who is not kin, but after acclimating to our home and the woods, they become emboldened. By dusk, around the fire, they insist on telling ghost stories.

When there’s a lull in the conversation, I gravitate toward my pet topic, UFOs. I saw an episode of Unsolved Mysteries about sightings in 1969, when dozens of families living in the Berkshires spotted an unidentified spacecraft that lingered in each small town as if the aliens were on a safari of small-town White America. I test out my theory that the UFOs might not be aliens but us, traveling back in time to study our evolutionary past. Since Egyptians and Ancient Greeks have spotted these spacecraft, witnesses have consistently described these aliens as humanoid, bipedal, and large-headed. Why would extraterrestrials from another galaxy look that humanoid? Why would they take such a keen interest in Earth when there are an infinite number of planets with possible life? And why would they take such care to only observe from afar, rather than wiping us out? I am met with amused expressions from our company, and your father tells them that I’ve been repeating this theory to him nonstop. As I turn to rebut something your father said, one of the twin boys begins to shriek that aliens will attack us, his increasingly loud wails piercing the dark bowels of the forest around us, stirring the wildlife within.

Since the pandemic, I have become frustrated with the linearity of time, how it speeds past us like a bullet train without stopping for us as passengers.Your father admonishes me for not being aware of the audience to whom I was speaking before he departs for the house. The mother consoles her boy but when he won’t stop crying, she turns stern, telling him she’s had enough. UFOs are not real, just like ghosts and vampires aren’t real. I am sheepish that I didn’t take heed of the children around me, though you remained unperturbed and sanguine, perhaps because you are still unaware of the phenomena of UFOs.

Since the pandemic, I have become frustrated with the linearity of time, how it speeds past us like a bullet train without stopping for us as passengers. I want to halt this train. I want to believe that we will evolve into hairless, benevolent beings, with the advanced technology to loop back in time to tour our past selves, which we will implement for study and not for harm, with the caveat that I understand that our quest for knowledge can cause its own harm. If we from the future have been detected by our ancestors, they would only be able to fathom what is unfathomable as further proof of God.

Maybe I embrace this theory because I can’t imagine too many generations after you, because of our human follies, and it’s my way to reassure myself, and you, that we will find a way out. My theory makes me not a New Age crackpot but a depressingly pragmatic secularist because I’m thinking that it wasn’t God or even aliens. It was us, all along. I am tempted to tell the boy my motives behind my theory. But instead, I echo his mother and tell him that none of what I said is real. The boy continues to weep unconvinced, protesting that I talked about UFOs as if they were real.

Just then, your father returns carrying a mason jar. Inside it is a toad. I found this little jerk trying to get in the basement, he says. A little water slides around the jar. What’s that, you ask. Toad pee, your father says. The boy immediately stops crying and runs up to the jar, demanding to hold it, which sparks an argument between you and the boys over who gets to hold the jar first.

Mom

_________________________________

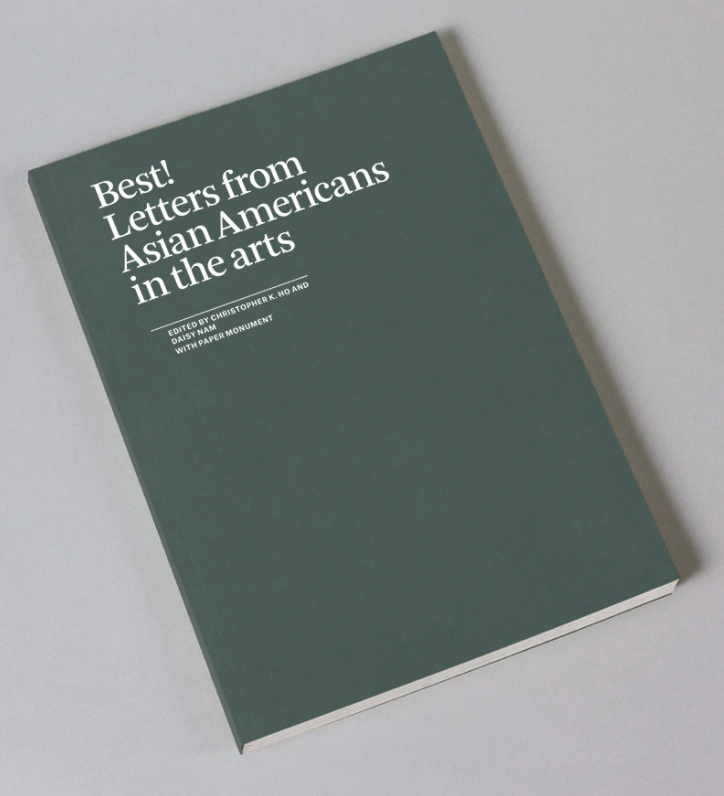

From Best! Letters From Asian Americans in the Arts. Available now from n+1 and Paper Monument.