Letter From Mni Sóta Makóče: “No One is Illegal on Stolen Land”

Heid E. Erdrich on What It Means to Fight For Your Home

This is a place where some creatures, when gassed and shoved, bloom with butterflies and song, where jelly dongs rain down upon our enemies and where a censored snow sculpture melts and resolves into bronze. But Minneapolis is not new to such fantastic transformation. And it is not surreal. It is something beyond itself and not business as usual. It is hyper-real.

Minneapolis is medicine. I mean medicine in the way colonizers translated our Indigenous languages. The “Medicine Line” is one translation for the Canadian border—it is a line seen with the spirit. Minneapolis is imbued with such spiritual power. Not just now while under assault by federal forces, but ever. This is a place built by glaciers, great water and millions of years of it. No wonder my mind shifts like tectonic plates—what they call a cataclysm.

Here I live in what Dakota people call Bde Óta Othúŋwe, the oldest name we have for Minneapolis. In Ojibwe we call it Gakaabikaang. Those words refer to the water and shapes that remain after geological upheaval. I could give you the denotation for those words, but who am I to explain languages I barely know?

The Ojibwe Word of the Day posted January 29th, 2026 is: “Daashkikwadin, there is a crack in the ice.”

Connotation is what matters. Home. Those words mean home to me and thousands of Indigenous people, some from Native nations, more who are Indigenous from elsewhere but at home here. We are a city of Indigenous relatives with a core of Native resistance—the birthplace of AIM, the American Indian Movement. And we are occupied on unceded Dakota territories, ever. I’m not the one to tell Dakota history. But trust me, Dakota history is everywhere in this—ICE detains people on the site of what was once a concentration camp for Dakota people.

Don’t ask us how we are doing, ask us WHAT WE ARE DOING. Minneapolis knows how to do mutual aid and protect the community.

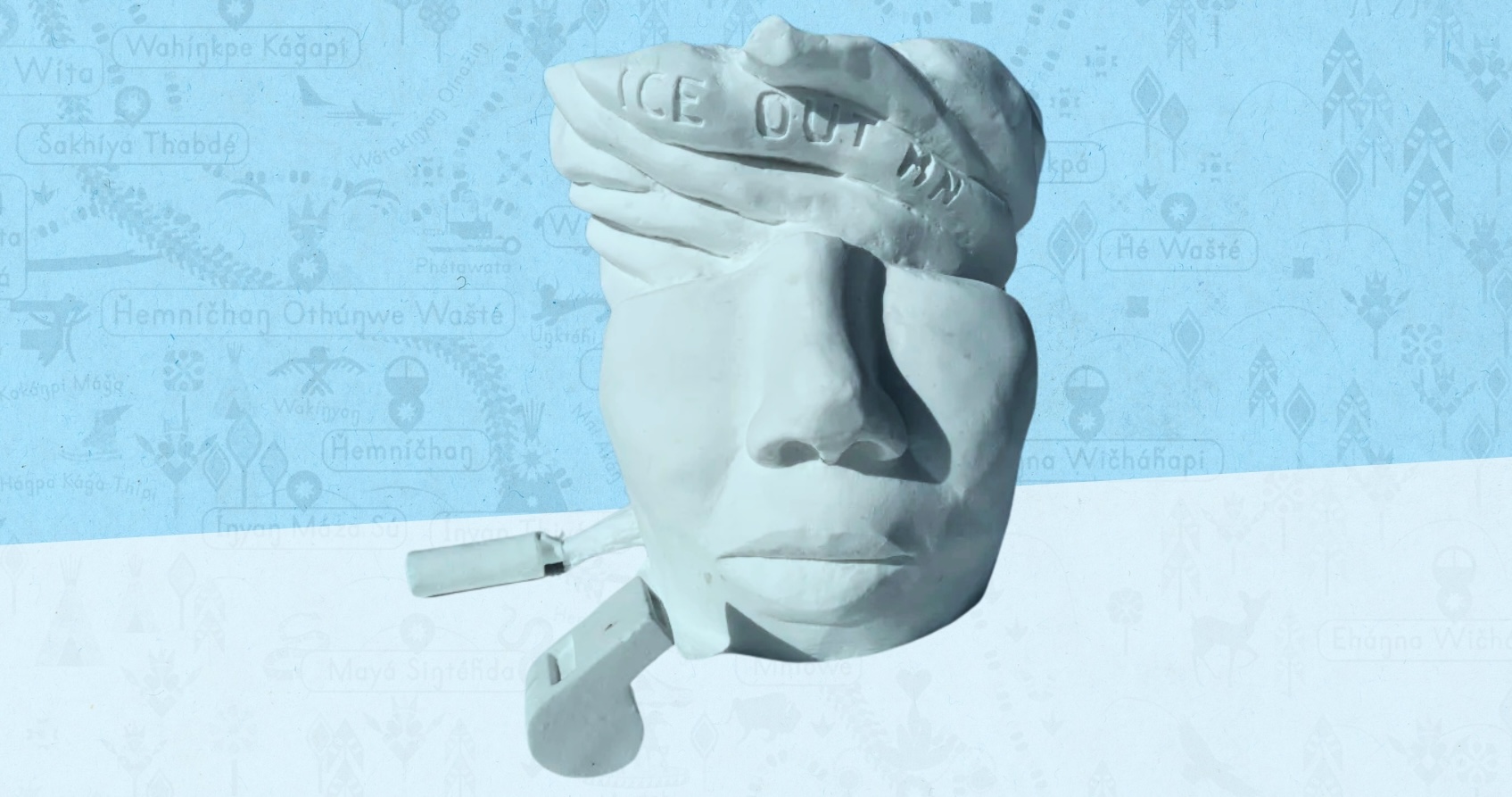

If you were here, chances are you wouldn’t need me to explain what Minneapolis has come to acknowledge about this land. The work of Native artists here carries and amplifies collective messages as quickly as other communities don blow-up costumes. A few days ago an overpass was lit with the words “NO ONE IS ILLEGAL ON STOLEN LAND.” Thousands in the Twin Cities community printed tee shirts and posters with a design around the original name for our state “ICE OUT OF MN SÓTA MAKÓČE.” It was created by an artist who is Dakota and printed by an artist who is Ojibwe and a hugely diverse team.

When a sculpture is censored and destroyed, a snow sculptor who is Odaawaa immediately leads a team to recreate the art elsewhere. Art actions led by Native and Indigenous people happen every day here. That is power—that is medicine.

This letter is likely too oblique, no doubt, too fragmented. It is not in the tradition of the epistle. Perhaps not an offer to correspond. I am no correspondent. Accept this witness as a journal glimpse. The revolution is quite a bit busier than I thought it would be.

Minneapolis is the home we love with our whole big hurting hearts. A city of lakes, creeks, springs and the big river, Mississippi or Gichii Ziibi in Ojibwe. In my mind, our city is a body, alive and coursing through us, even where sacred streams are sluiced under streets. In winter we are not frozen, but dreaming, doubled-down creative, making medicine out of the cold element and this year more than ever. Huge messages light up on our lakes telling military helicopters where to go. There’s so much tension here that art sometimes can break while also calling us to action. And so very, very much of it is led by Native people.

When someone outside Minnesota asks how I’m doing I usually say I’m fine but worried about everyone else. If someone asks what it’s like here I’ve said it’s hideous, a shitshow. Sometimes I just say “you know…” asking more for solidarity than taking a chance to describe. It is at once usual and hard to describe. And many others have done it better than I will. Sometimes I’ve said that our city is good at this. I’ve said “Our hearts are not yet on the ground.” In the early days I said, “We’ve got this.” Or bragged that they picked the wrong place in the wrong winter.

Do us a favor, don’t ask us how we are doing, ask us WHAT WE ARE DOING. Minneapolis knows how to do mutual aid and protect the community. There are thousands of people here meeting the daily needs and need for safety for thousands more. Those people called protesters are also protectors. The Native community especially knows how to go to ground for our own. We learned it at Standing Rock. We learned this in 2020. We learned it long ago. They did pick the wrong place. Minneapolis is medicine.

For the sake of all of you and especially for wherever ICE masses next, ground yourself in the medicine of your place. We are momentary, but place endures.

Sometimes I ask myself how we are doing. I send myself texts and email myself notes. I keep a file in my mind, in my inner eye. My visions are sometimes overwhelming: lacing my hands to hold a frozen pool of words, echoes really. I’m holding the sound of a gray-bearded resister, who feds yell at “Go home!” He yells back “This is my home. Where is your home?”

After her wife and poet Renee Good was murdered by ICE, Becca Good wrote, “We stopped to support our neighbors. We had whistles. They had guns.” And now echoes asking who shot Alex Pretti and ICE mercenaries who reply time and again, “Not me.” The evil gloat of ICE goons who said they detained a woman “as a joke.” There are hideous videos in that frozen pool in my hands, too: that woman crosses herself and falls to her knees begging, in her arms a small child in a pink snowsuit, and in the child’s hands an ice cream cone.

My college-aged kid tells me that clouds formed in the thick of last week’s march. Everyone’s breath freezing as they called for justice. Are these words ghosts? Are they trapped here like our breath on frigid air?

Perhaps they are medicine—yes, they are medicine—the sound of hundreds of Native women dancing in jingle dresses to heal the sites of murders.

What am I doing? I saw that snow sculpting teams in the world and state competitions had their work disqualified and destroyed by the host organizations because they had anti-ICE content. The teams were willing to combine their works in a new sculpture, so I secured the space and am collaborating to incorporate poetry in their new work entitled ICE Out for Good.

Last night I joined other Mni Sóta poets laureate at a long-planned event for the City of Minneapolis. We could not treat the event as lit biz as usual. I shared my note-like “journal” entries with my language around echoes of other’s poems and these words for January 19th, 2026 that a friend printed poster size:

Just US

-v-

Just ICE

Jeez us

fn krice

How am I doing? What am I doing? I had the privilege to get up and read some lines from poets John Trudell, Nimo H. Farah, Ed Bok Lee. I repeated some of the ghost phrases in that pool in my hands. To see if they thaw indoors. To see if they would make a cloud of our voices. To see if they made medicine.

Heid E. Erdrich

Heid E. Erdrich curates art exhibits, teaches, researches, and collaborates with other artists. In 2024 she was the inaugural Minneapolis Poet Laureate and in 2025 she served as the James Welch Distinguished Visiting Professor at University of Montana Missoula. Erdrich is Ojibwe and an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa. Her most recent books are Boundless: Abundance in Native American Art and Literature (co-edited, Amherst Press, 2025) Verb Animate -Poems, Prose, and Prompts from Collaborative Acts (Trio House Press, 2024) and National Poetry Series winner Little Big Bully (Penguin 2020).