Letter From Minnesota: Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Frontier, From an Immigrant in Minneapolis

Sun Yung Shin on the Ever-Shifting Meanings of US Citizenship

“For over a century, the frontier served as a powerful symbol of American universalism. It not only conveyed the idea that the country was moving forward but promised that the brutality involved in moving forward would be transformed into something noble.”

–Greg Grandin, The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America

*

1. O say can you see… Francis Scott Key, an American lawyer, was the author of the national anthem, whose original title was, “Defence of Fort McHenry.” In 1814, Key set his lyrics to an English tune that was written circa 1780 by two British men who were members of London’s Anacreontic Club. The London club’s theme song was titled “To Anacreon in Heaven,” named for a Greek poet who died in 485 BCE. What was the purpose of this club? The Anacreontic Club “was a group of wealthy [white] men who met to celebrate music, food and drink.”

2. …by the dawn’s early light… I have lived in Minneapolis for the better part of 34 years. I grew up in a suburb of Chicago. I am a naturalized immigrant, a former resident alien, a former orphan who was born in Seoul, South Korea, during Park Chung-hee’s military dictatorship, a reign that was born in a bloodless coup in 1961. During his regime, political parties were eliminated, opponents were executed, and Park named himself president for life. He was indeed president for life, as his presidency ended with his assassination in 1979.

3. …What so proudly we hailed… Because of my origins, and the way in which I became an immigrant—legal alien resident—then naturalized citizen of the US, I think about authoritarianism frequently. Because I’m not a man, and the world is ruled and owned mostly by men, and my survival depends on a daily basis on the decisions I make around my behavior when interacting with men, I think about masculinity frequently. Because the country and the world into which I was born was controlled militarily by white nations, I think about whiteness on a daily basis.

Because I live in a nation with approximately 400 million guns in circulation, I think about death by firearm every time I leave my house, and often times when I don’t. Because I’m a mother, and because I care about other people, and especially when I was a public high school teacher, I thought about statistics like this on a regular basis, “The US has the highest gun death rate at 10.6 per 100,000 people.”

4. …at the twilight’s last gleaming… On May 25, 2020, close to where I live, members of the Minneapolis Police Department created a hole in the universe, a checkpoint to the afterlife, on Chicago Avenue and 38th Street. On that cataclysmic day, George P. Floyd’s primary executioner, employed by my city’s government to “serve and protect,” was a white male US citizen. He is still a US citizen.

Renee Macklin Good’s executioner is married to an “Asian American” (Filipina) woman who is presumed to be an immigrant (based on what her father-in-law said, or wouldn’t say, about her).

US citizenship protects some, but it has never been a protection for millions of others. Ask any of the Native people here who have been arrested and disappeared by ICE. Ask a member, or a descendent of a member, of AIM, the American Indian Movement, which was founded here in Minneapolis. Ask a descendent of one of the Dakota 38 + 2, whose warrior ancestors were hanged in the largest mass execution in the United States, signed by President Abraham Lincoln, at Fort Snelling, where Liam Ramos and his father were taken to be processed at the Bishop Whipple Building before being flown to a private prison in Texas.

5. …Whose broad stripes and bright stars… Ask any Native person anywhere on Turtle Island what they know about what being born on and being of this land—“since time immemorial”—means in terms of protection from the federal government. Ask a Native person why Native people have volunteered to fight in the US’s wars overseas, including in Korea, my homeland, and Vietnam, the most recent nation of origin of many of my refugee friends.

The current administration would have us believe that being a patriot means cheering and advocating for the potential “denaturalization” of someone like me, an immigrant, a woman, a mother, a writer, an educator, an artist, and someone who regularly exercises their right to criticize their government in the collective effort to hold our elected officials—paid by our labor—in their gleeful, abject, incompetent, and catastrophic abuse of power.

6. …through the perilous fight… In American Indian Magazine’s article, “Patriot Nations: Native Americans in Our Nation’s Armed Forces,” the editors enumerated and honored Native veterans, including those who served in Korea and Vietnam—two wars that the US government leadership, whose entirety long-consisted of only of white male US citizens, and has never not consisted of a majority of white male US citizens:

Korea

The Korean War began in June 1950, when Communist North Korean troops crossed the 38th parallel dividing the Korean Peninsula. For the next three years, American forces—including approximately 10,000 American Indian soldiers—along with troops from 15 other nations, fought to prevent a Communist takeover. Considered a “police action” because Congress issued no formal declaration of war, the Korean War was nevertheless bloody and brutal. Some 33,739 American soldiers died in battle, including 194 Native Americans.

Vietnam

Of the 42,000 American Indians who served in the US armed forces during the Vietnam conflict (1964-75), 90 percent were volunteers. Approximately one of every four eligible Native people served, compared with one of twelve in the general population. Of those, 226 died in action and five received the Medal of Honor.

Like many other Vietnam veterans, American Indians were often deeply traumatized by what they experienced. Some noticed similarities between the Native and Vietnamese colonial experiences. As one veteran observed, “We went into their country and killed them and took land that wasn’t ours. Just like the whites did to us. We shouldn’t have done that. Browns against browns. That screwed me up, you know.”

7. …O’er the ramparts we watched… Because I was adopted by white US citizens and because they filled out numerous government forms to obtain my naturalization*, I, an Asian American child at the age of five, did not have to fight for my civil rights like the generations of Native people who lived here on this continent before any of my American family’s German and Polish immigrants arrived to Chicago in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Minnesota’s current governor, Tim Walz, is 61 years old. Minnesota has never had a governor who wasn’t a white man. What you see on the streets of Minnesota right now, are people of all backgrounds governing themselves.

For Native people here, before 1924, being subject to the laws of the US government didn’t mean being afforded the protections of US citizenship. Ask a Native person how the US’s genocidal policies and broken treaties continue to affect this country’s laws of belonging: “In its attempt to end birthright citizenship, the Trump administration has cited a 19th-century lawsuit that denied US citizenship to Native Americans. The president’s executive order has been blocked by multiple federal judges, and his use of Elk v. Wilkins to justify the order is generally deemed invalid by legal scholars. But the use of the lawsuit has raised concerns over immigration enforcement in some Indigenous communities, even though Native Americans were granted [US] citizenship in 1924.”

8. …were so gallantly streaming?… As I said, I am an “Asian American” “woman” (femme, person, human, earthling, etc.). Who cares? Well, the white male US citizen Vice President is married to an Asian American (Telugu Indian) woman. She was born in San Diego, California, but I bet white people used to ask her all the time where she’s from—and felt entitled to an obedient reply.

Renee Macklin Good’s executioner is married to an “Asian American” (Filipina) woman who is presumed to be an immigrant (based on what her father-in-law said, or wouldn’t say, about her).

George P. Floyd’s main executioner was, at the time of the public lynching, married to an “Asian American” (Laotian) woman, an immigrant, a refugee. She filed for separation the day before Floyd’s murderer “was charged with third-degree murder and involuntary manslaughter.” She, who was crowned Mrs. Minnesota in 2018, and who was born the same year I was, in Asia, filed also for a name change, and today no longer shares a last name with Floyd’s killer.

9. …And the rocket’s red glare… The Korean peninsula, my homeland, and the place where my ancestors’ bodies were, in the Bronze Age, placed in expertly-made clay coffins and buried upright in the ground, has been divided by one of the most militarized borders on planet earth.

This border was created on July 27, 1953 through the armistice agreement which was signed not by any South Korean leaders, but by United States Army Lieutenant General William Harrison Jr. and General Mark W. Clark.

I’ve visited the surreal wartime open-air theater known as the DMZ twice.

Today, there are millions of US-made landmines buried, like poisonous secrets, in the soil of the DMZ and in the peninsula. The US remains the world’s largest arms dealer.

10. …the bombs bursting in air… I thought about these landmines in the body of my homeland—US weapons of war that scholar Eleana J. Kim calls “rogue infrastructure and military waste,” when I saw how ICE agents in Minneapolis, like circus clowns rushing to get back into their clown cars, were dropping not colorful juggling balls and pins, but magazines of live ammunition on the snowy, icy ground, sometimes after being run off by small groups of everyday Minnesotans bearing whistles, mittens, and perhaps some handmade signs.

11. …Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there… I am not a white US citizen but I live in a country where white male US citizens regularly murder—massacre—other white US citizens in what is defined as a mass shooting. I live 1.5 miles from Annunciation Catholic Church, where two children were murdered and eighteen children and three adults were shot and injured by a white US citizen who is, from sources found, a trans person who (legally, not that it should matter) changed their gender to female and their first name from a traditionally masculine name to a gender-inclusive name. And no, there is not an epidemic of violence committed by trans people; there is the exact opposite.

12. …O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave… As an immigrant and person of color in Minneapolis, as someone who has seen, daily, over three decades, how white culture in Minnesota has evolved, that when this particular occupation is over, I, we, will still live in an occupied place, in an occupied land.

I do not yet see enough white activists crediting queer Black femme organizers or Native activists or labor activists or disability justice activists for the creation of mutual aid infrastructure through decades of teaching and capacity building. These lineages of genius and generosity, our inheritances of these epistemologies and practices may soon become our only defense, our only offense, and our only wealth.

I have been taught and shown that solidarity is the only answer, and this mass movement of people’s liberation needs as many people as possible if we are going to make it through to a better place. We don’t have to agree on everything, we don’t have to be more pure than the next person, we just need to remember our humanity, and that we center those most impacted. I hope new activists will be hungry for more when this occupation is over. More solidarity, more learning, more hope, more grit, more joy of working side by side.

13. …O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? Please allow me to close with a few things that I think about nearly every day, because my life here, and throughout this country, depends on the good will of white people, who hold the most power in the US, and are the majority of this state—76.3 percent being “non-Hispanic whites.”

Minneapolis is slowly closing in on being a city in which people of the global majority outnumber white people. As of the last census, 58.1 percent of the residents of Minneapolis are “Non-Hispanic white” people.

White supremacists are afraid of replacement, because somewhere deep down, their cells remember that the ideology they follow is responsible for crimes against humanity, globally.

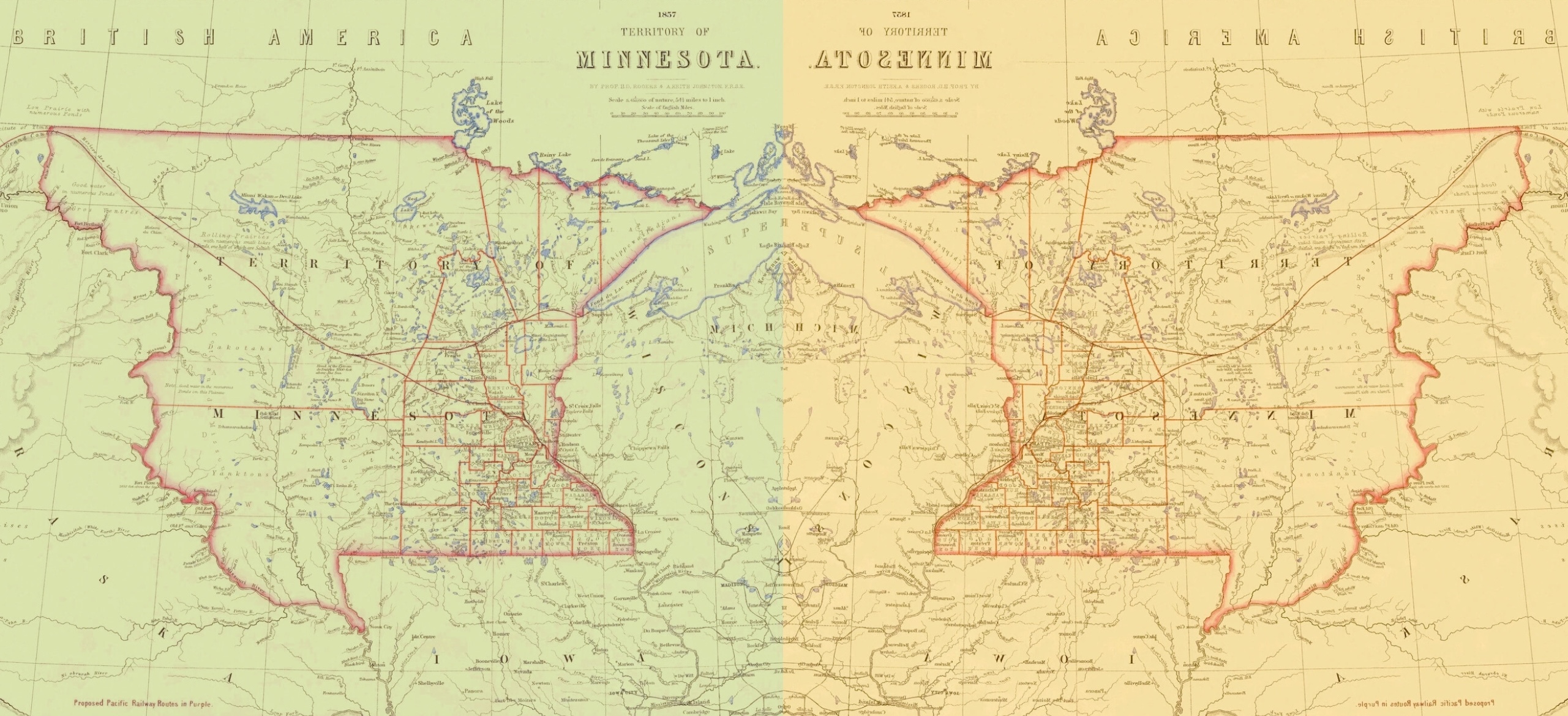

Land of the… home of the… Here, where I live, by 1850, the Minnesota Territory had nearly achieved its goal of ethnic cleansing of Native people—its counted population was 99.4 percent white.

Eight years later, in 1858, three years before the Civil War, Minnesota Territory became the US’s 23rd state, earning a new white star on the American flag.

When I moved to Saint Paul, Minnesota in the late 1900s (1992), the state was 94.4 percent white. The people who own the most in Minnesota, white people aged 65 and older, if they grew up in Minnesota, that was the Minnesota that raised them. In 1990, they were 35 years old. Six years ago, in 2020, those Minnesotans who were 65 years and over, 92.4 percent were white.

Minnesota’s current governor, Tim Walz, is 61 years old. Minnesota has never had a governor who wasn’t a white man. What you see on the streets of Minnesota right now, are people of all backgrounds governing themselves. As all people under the boot of power have always known, power—or liberation, as many activists say—is never truly bestowed on the people because it’s the right thing to do, it has to be fought for, again and again.

P.S. …O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? Thank you to everyone in and beyond Minnesota who are mobilized to protect all of our civil and human rights. Allow me to leave you with this, as we live in the present and think ahead to activism in the future, about how we understand the story of colonialism and capitalism and how racism makes them both possible in their current forms. In 2024, Minnesota changed its state flag, which began like this—look at the story it tells:

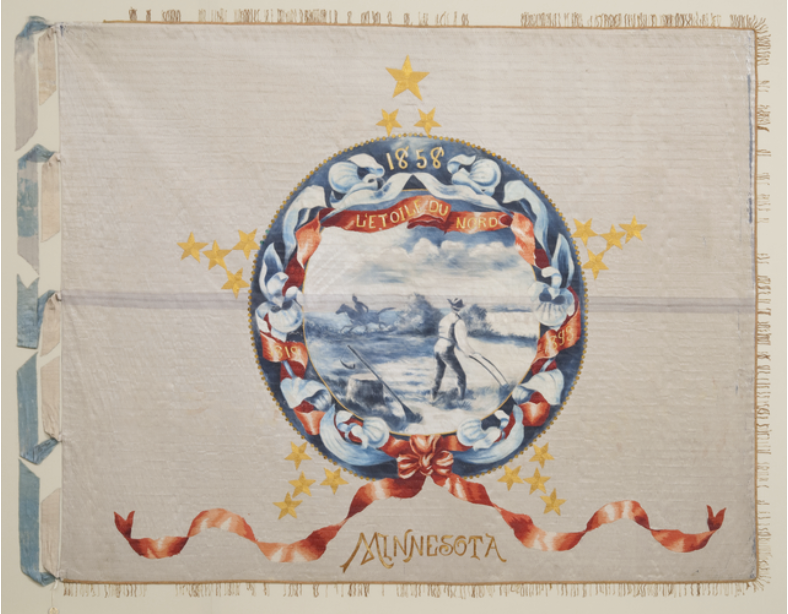

Then for many years was this, telling the same story:

And on May 11, 2024, Minnesota’s flag officially turned into this:

This administration loves its American flag, perhaps unlike any other before it. In an undated photo gallery on the White House website, the headline “President Trump Raises New American Flag on South Lawn of the White House” is followed by 41 photos of this event.

The most prominent feature of the Whipple Building at Fort Snelling is a tall pole bearing an American flag. We know what Fort Snelling stands for. We know what the anthem valorizes. We know who and what the Department of Homeland Security and what ICE values. When this occupation is over, before the next one, and during the ongoing one, what will we value? What more will some of my white neighbors be willing to do because they “love [me] their immigrant neighbor”? Time will tell, until then, I will continue my bumper-sticker Gramsci-inspired practice: pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.

________________________________________

*Any transnationally adopted person to the US who arrived after the Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2000 did not receive citizenship as if they were the birth children of US citizens, even though all transnational adoptees who are processed through legal means receive new “birth” certificates to replace their original birth certificates, if they have them, and which are an addendum to their US-created “certificate of foreign birth.” Perhaps tens of thousands of US citizen married couples (made up of one “man” and one “woman”), mostly (but not all) white, failed, despite instruction, to obtain naturalization for their children they adopted from South Korea, via proxy adoptions (meaning they did not have to travel to South Korea; their child was brought to them by an escort, a civilian who received an airline ticket discount for their supervision of these unaccompanied minors).

Sun Yung Shin

Sun Yung Shin is the author of thirteen books, including forthcoming essays collection Heart Eater: A Memoir of Immigration, Belonging, and How We Find Ourselves in Language (July 28, 2026). She is the author of five books of poetry, including Six Tones of Water (2024) co-authored with Vi Khi Nao; she is the editor of three anthologies of essays including What We Hunger For: Refugee and Immigrant Stories on Food and Family (2022). Also a children's book author, her latest picture book is Revolutions Are Made of Love: The Story of James Boggs and Grace Lee Boggs (2025). Her books have won an Asian American Literary Award, a Minnesota Book Award, a Carter G. Woodson Award, and other honors. She has been awarded a fellowship from the MacDowell Foundation, two McKnight Artist & Culture Bearer Fellowships, and others. Born in Seoul, Korea, she lives on Dakota land in south Minneapolis, where she co-founded Poetry Asylum with poet Su Hwang. She teaches in many places, including with the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop.