Letter From Minnesota: SOS From an Occupied City

Angela Ajayi on the Feeling of Authoritarian Creep

The first words I hear about ICE raids are rushed and a little hushed. They come from neighbors with family connections in small cities like Dassel and Cokato, nearby places I have never visited despite having lived in downtown Minneapolis for over ten years. Fall of 2025 drags on longer and warmer than usual, the leaves bursting with vibrant colors, and as the weather gets cooler, my awareness of ICE is heightened mostly by the alarming news from social media. But it all still feels distant and isolated to me as a naturalized American citizen living in the North Loop, a predominantly white and trendy neighborhood.

Of course, the mind will make its own calculations when faced with potential danger, however distant it might appear to be at first. I came to this country as a Ukrainian-Nigerian student in 1993, graduated from college after four years, and then worked legally for many years until I obtained a green card through a job. In 2016, I applied for citizenship and was sworn in at a touching ceremony in St. Paul, where a welcoming message from President Obama was broadcast across a large room filled with people of all races. That day, with my husband by my side, I held onto my little American flag with pride.

Is there any reason I should fear for my own safety now as ICE agents occupy my city?

Over coffee and pastries at a German bakery in the Northeast neighborhood, old friends ask me a similar question in the fall of 2025—are you in any danger? I shake my head and say, not really, I don’t think so. But the truth is, as a mixed-race person with brown skin, I am never sure if I will be perceived as threatening or non-threatening, never sure if I am ever completely welcome here.

And then by early December, Trump is spewing more virulent anti-immigrant rhetoric. He directs his ire at the Somali immigrant population in Minnesota, many of whom are either naturalized citizens or born in the US. He says he doesn’t want them in this country. He calls them garbage, using loud, nasty words. This coincides with a steep drop in the temperature outside. It is frigid, and there are even more sightings of ICE around the city now. More raids. Increasingly more aggressive behavior from federal agents.

On the internet, videos proliferate, showing masked men in bulky green uniforms, wearing bullet-proof vests and carrying guns, rounding up almost anyone it seems. The scenes in the videos are chaotic, filled with haunting cries and the piercing sounds of whistles from shaken immigrants, from empathetic observers who have been alerted to the presence of ICE. My husband orders a pack of ten red whistles and wears one around his neck.

Around that time I notice that my passport is expiring in a few months and I must apply for a new one. Now there is talk that even naturalized citizens can be deported. Nothing appears to matter anymore. What we imagine as having real meaning doesn’t, especially in a country that is starting to resemble an autocracy. I apply online for a new passport, not entirely sure if it will get approved. Minutes later, I get a message from a GovAssist email address saying the process will take four to six weeks.

By now the word is definitely out: brown and black people are being targeted, no matter their status, legal or not, in the country. Nothing is subtle anymore.

During a visit to Chicago after Christmas, my friend and I talk about writing and politics, and it is clear from what she is telling me that Chicago is reeling from its own recent fight against ICE. We agree that the situation in Minneapolis is seemingly worse, increasingly worrisome, though we are unaware, on that one-off warm, foggy day, that things are about to get far worse and those hushed words, said earlier in quiet disbelief, will turn into sounds of wailing sirens.

After New Year’s Day, I choose to spend my afternoons away from my desk and in a coffeeshop, working on a book manuscript. On yet another brutally cold day, I notice the door to the coffeeshop is broken, the latch bolt ripped apart and hanging askew. It looks like someone forced their way into the coffeeshop, and each time the cold wind blows, the door creeps open and one of us gets up and closes it. There is a constant chill in the air.

The next day, a sign goes up, prohibiting federal agents from entering or attempting to stage operations in the coffeeshop, per a judge’s recent order. I am afraid to ask questions, but I put two and two together, remembering that a Somali elementary school sits around the corner. I decide to start carrying around my passport which, to my great relief, has been promptly renewed and mailed to me.

By now the word is definitely out: brown and black people are being targeted, no matter their status, legal or not, in the country. Nothing is subtle anymore. People are using expletives to refer to ICE. In a text to a friend in Amsterdam, I remain defiant. No, I will not stop going to the coffeeshop to do my work. Yeah, fuck ICE. The words are getting louder. The city is fighting back, harder, angrier. When I visit our small corner store, owned and run by hardworking immigrants, I see they too put up a handmade sign that prohibits the wearing of hoods and masks.

Then, on January 7, the unthinkable happens: Renee Good, a mother, a poet and intrepid observer of ICE, is shot and killed in South Minneapolis. As the video of her horrific killing circulates and the Trump administration shrugs off accountability, I feel sick, nauseated, and infuriated all at once, as I fall into the white-hot grips of a head cold.

On January 8, a friend who owns an antique store in a neighborhood across the Mississippi River and less than a mile away, posts a disturbing video on Instagram. In it, a slim, white woman with greenish hair is surrounded by ICE agents trying to handcuff her and shove her into an unmarked car. She is kicking and screaming; her friend is begging them to leave her alone. The woman with greenish hair is finally forced into the car, but seconds later, she opens the car door and sprints across Central Avenue, a wide and busy street in a heavily immigrant neighborhood. The ICE agents catch up and tackle her violently to the cold sidewalk. A friend in California texts and asks me where ICE is taking people they arrest and put into unmarked cars. Probably the federal building, I say, out by Fort Snelling.

In the next few days, there are protests across the city with people carrying ICE OUT signs, demanding that federal agents leave their city, that agents be held accountable for the death of Renee Good. Helicopters whirl constantly above our building, zipping here and there. I am feeling sick and disappointed that I can’t go out to protest. Snow falls then freezes into ice on the sidewalks and along the edges of streets.

While lying in bed, I pick up Lola Lafon’s new book, When You Listen to This Song, about the night she spends at the Anne Frank House. I get to page 19 and read the pressing question, “Can you get used to living in danger?” I shut the book, thinking about all the people, many of them black and brown immigrants, hiding in their homes afraid to venture out for food, to go to work or send their children to school. I put the book aside.

On January 23, a massive protest is held in downtown Minneapolis and it snakes its way, loudly but peacefully, near us toward Target Center. I see it as a glimmer of hope on another frigid day.

Then, on January 24th, while out running errands, the new passport in my bag, my husband tells me to avoid the area known as Eat Street. There’s been another shooting. I check the news and see that Alex Pretti, ICU nurse and intrepid ICE observer, has been killed right in front of Glam Dolls, a bakery where my daughter and I once bought Halloween-themed donuts for a birthday party, charming ghoulish faces staring at us from inside a pink box. I feel the onset of another cold. I get texts from friends asking how I am doing. I tell them I’m hanging in there but definitely not okay, even while watching a video of Border Patrol Officer Gregory Bovino leaving Minnesota, his car being pelted with snowballs.

It is February now, and at last, the temperatures inch toward the twenties and thirties. It feels, refreshingly, like a heat wave, a small reprieve in a battered city. Breaking news comes at us fast. The Epstein files have been released and everyone is talking more about its contents and less about ICE. Don’t be fooled—the situation here is still unabatingly dire.

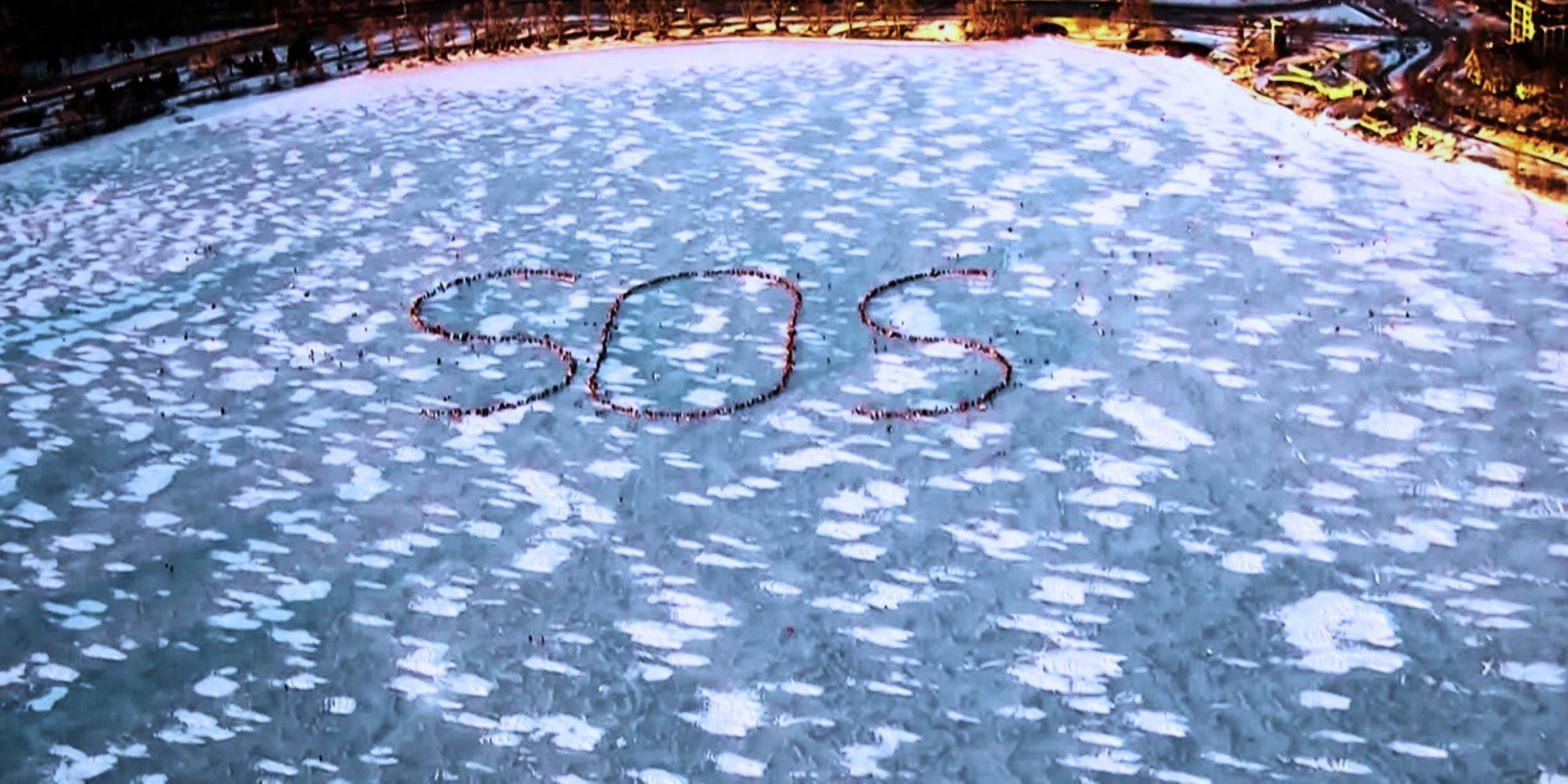

Last weekend, on our way back home from donating used books, my daughter and I drive by one of the largest lakes in Minneapolis, Bde Maka Ska, which looks beautiful as the sun dips low in the horizon. The lake is frozen many inches deep from weeks and weeks of ice-cold weather. Bundled up in thick coats, scarves, hats and gloves, people are walking across the lake. We aren’t sure what’s happening; we think it’s some kind of protest, many of which are being held daily on street corners, on highway overpasses and in front of that federal building in Fort Snelling. But it won’t be long before my teenaged daughter will hold up her phone and show me a drone picture of hundreds of people standing on an icy lake in Minnesota. Loudly, painstakingly and still so urgently, they spell out SOS.

Angela Ajayi

Angela Ajayi’s essays, book reviews and author interviews have appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Common Online, Wild River Review and the Minnesota Star Tribune where she was a contributing book critic. Her first story, “Galina,” published in Fifth Wednesday Journal, won the 2017 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers. A short story, "Our Beautiful Ukrainian Mothers,” was also published in Pleiades and nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She has a novel-in-stories, Everything Is Freedom, forthcoming from Forest Avenue Press in Spring 2027.