Letter From Minnesota: Our Work is to Protect What We Love

Diane Wilson on Traditions of American Violence,

to Nature and Human Alike

For thousands of years before ICE made the Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building the home base for their sweeping immigration roundup, this place has been known to the Dakota people as Bdote, where two waters come together, the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, and the center of our creation story. We are also known as the Wicahpi Oyate, the Star People, whose spirits came from the Milky Way and emerged here as human beings. We respect water as our first medicine and the places where she gathers as sacred.

The building named for Bishop Whipple, who was a dedicated advocate for Native people, has become a place of fear and uncertainty for the alleged illegal immigrants who have been arrested in traffic stops, at their child’s school, the grocery store, at their job. This group includes profiled citizens and legal observers. Outside the building, a group gathers to protest the ongoing violation of civil rights.

This is not the first time that Bdote has been desecrated.

Fort Snelling, which includes the Whipple Federal Building, was first established on this sacred place by the US government in 1819 as a military fort to control trade and enforce treaties. After a short-lived war in 1862 that erupted from treaty violations, loss of homeland, and families who were starving while the food and goods owed to them were locked in a warehouse, the Dakota warriors were convicted in sham trials that lasted five minutes or less. They were sent to a prison camp at Davenport, Iowa, while 38 were infamously hanged in Mankato on December 26, 1862, the largest mass execution in US history.

But it was the women, hungry and weary and frightened, left alone with their children and the elders, who had been marched 150 miles in November to a concentration camp at Fort Snelling, not far from where the Whipple Building now stands. After a bitterly cold winter in which hundreds died, the remaining 1,600 were loaded onto flat boats and forcibly removed from Minnesota, their homeland for many thousands of years. And then they came for our children with their boarding schools. This history haunts us still.

This is the place ICE has chosen to detain its prisoners, often illegally, without due process. Breaking apart families, terrorizing children, eroding democracy, recycling history in an all too familiar echo of 1862. As masked agents clash daily with protestors, the trees along the road stand in silent witness, dark silhouettes wreathed in tear gas, victims without rights. I grieve for those trees as well. At the heart of Dakota culture is the belief, Mitakuye Owasin, that we are all related.

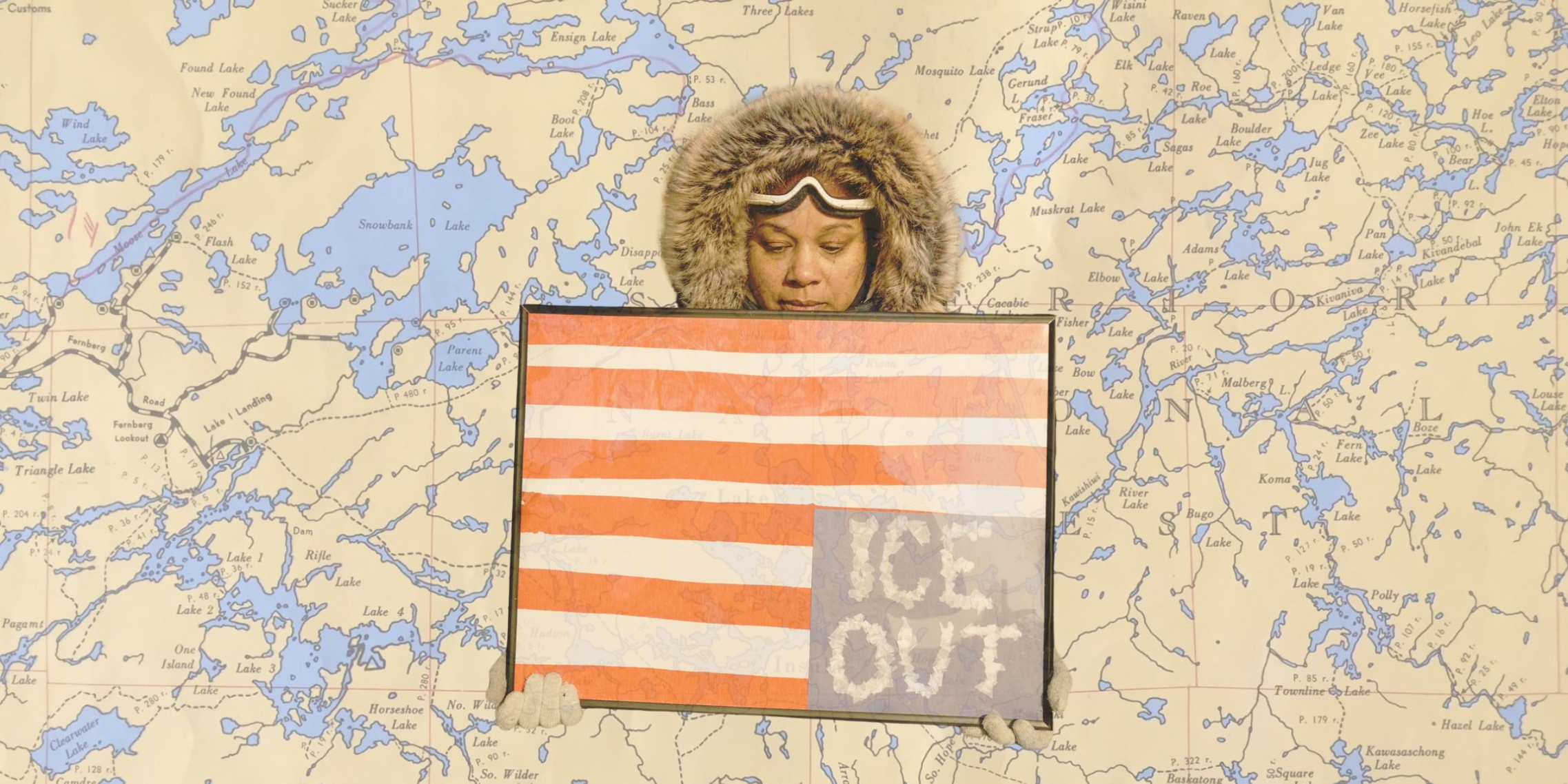

Just as local communities have shown up to protect immigrant families from ICE, people are also standing up to protect the Boundary Waters.

This philosophy means that we must also protect the plants, the water, and the land, the more-than-human relatives who provide everything we need. As we mourn the tragic killing of Renee Good and Alex Pretti, the attacks on our relatives come from many directions, some of them quietly announced while we’re looking another way.

Two days before the march on January 23, the US House of Representatives voted to overturn a 20-year ban on mining near the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, an area that shares the same watershed as the BWCA. The bill was introduced by Republican US Representative Pete Stauber, who represents northeastern Minnesota, including my county. The bill opens up the area to potential copper mining permits, threatening the watershed that sustains wild rice for northern Native communities who rely on this critically important Indigenous food to survive.

Manoomin or psiŋ or wild rice, thrives in wetland areas that also help prevent flooding, purify water, mitigate droughts, and provide wildlife habitat for more than one third of all North American birds. This past November, the EPA proposed new rules to weaken the Clean Water Act by stripping federal protections from millions of acres of wetlands and streams. I live next to a six-acre bog that is home to pitcher plants and pileated woodpeckers; how do I keep them safe?

In the past year, the federal government has moved to undermine the Clean Air Act, rewrite the rules for nuclear power plants to diminish protection for ground water, withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement, cut solar, wind and alternative energy development, and stop states from reducing emissions. While our communities are fighting for their lives, corporations are working to extract “resources” to expand water-starved AI centers, drill in wilderness areas, and destroy soil with production farming.

And yet, just as local communities have shown up to protect immigrant families from ICE, people are also standing up to protect the Boundary Waters. The lesson of Standing Rock in 2016, when Dakota people stood with thousands of supporters from around the world to prevent the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, showed us that our work is to protect what we love. We protect the water for the good of the earth, for all of our relatives.

There are so many ways to do this work. On a cold afternoon shortly after Pretti was killed, a small group of Native women came together to sing at Bdote. We wore ribbon skirts and carried hand drums, standing in circle not far from the river’s edge but far enough from the sounds of sirens and bullhorns. Our voices twined with the wind, rose through the cottonwood trees, encouraged the people held at Whipple to be strong, and reminded the land and the water that we are still here. We will always be here.

What the federal government has never understood, nor do these ICE agents understand it now, is that they have come onto our land, our sacred place, where the prayers of our ancestors have allowed us to survive. We know that children are wakan, sacred, and they should never be treated as political prisoners. We know the immense, enduring power of prayer that is fueled by love for community, for the land, and for the water.

To the federal agents, I say this: take a moment to look up at the sky, to see how eagles glide in slow circles high above the river. Look at the trees, dormant in winter, holding energy in their roots for the joyous unfurling of spring, a true celebration of new life. Within a few months, whether you are here or not, the sandhill cranes will return on their migration, following the river home. Perhaps no one ever told you that we are all beloved of the earth, that she asks only that we love her in return.

Imagine what your life might be like if you take off the mask, set down your gun, and find your way home.

Diane Wilson

Diane Wilson is a Dakota writer, educator, and bog steward, enrolled on the Rosebud Reservation. She has published six award-winning books as well as essays in numerous publications. Her novel, The Seed Keeper, won the 2022 MN Book Award and is a selection for the 2026 NEA Big Read. Wilson’s work explores seed sovereignty, social justice, cultural recovery, and environmental stewardship. She is currently working on a memoir, Mapping My Way Home: A Story of Love, Loss, and a Bog.