Letter From Minnesota: Lessons From Palestine on Surviving Occupation

Sana Wazwaz on the Long American Tradition of Occupation

I’m sorry I called you “dog boy” that July morning, dear Mohammad.

“That’s enough, my love,” you said, your final words as you petted the Israeli attack dog that mangled you limb to limb and ate your flesh alive. “That’s enough.”

You caressed the dog that tore your body open like it were a plush toy—your plush toy. Of course you did that. Of course you didn’t comprehend how man’s best friend could be primed to tear open olive-toned flesh like your occupiers do. I called you “dog boy” when I learned how you spent your last moment on this earth, holding close the very creature trained to slaughter you. I called you “dog boy” because in your precious autistic innocence, you reminded me of my own dog-loving beloved—my own autistic baby brother. You reminded me that you were someone’s loved one, someone’s everything, and someone else’s “terrorist.”

His name was Mohammad Bhar. He was a 24-year-old Palestinian with Down Syndrome and autism. His name was Mohammad Bhar and he loved to dance, play sports, and mulukhiyah was his favorite dish. He adored his mother, Nabila, who was widowed after her husband was killed by the Israeli military during a raid in Gaza City in 2002.

His name was Mohammad Bhar and I swear, by God, when his death made the headlines, I saw my baby brother in his precious face. A sweet teddy-bear boy whose home on Nazaz Street was raided by Israeli soldiers, violently separated from his family to a room where IDF attack dogs were unleashed on him. He was left to die alone. Mutilated to the bone by an animal he gently stroked until his last breath.

I called him dog boy because when I saw his soft face, I imagined that he loved dogs just like my sweet Muneer does. I called him dog boy because in his kind eyes, I saw my beloved who calls dogs perfect creatures. I saw that little boy who asked me that July morning, “But if the doggy didn’t know better, will he still go to heaven?” I didn’t know what to say.

I called him dog boy because I wanted my tender-hearted Muneer to believe that dogs trained to kill us could never really hurt anyone on purpose. I called him dog boy because canines are afforded more rights to life than a Palestinian.

Since that day, I wondered who would be the next “dog boy,” the next innocent person to be kidnapped, cornered, and ripped open—by bullets or fangs. I wondered, in this settler-colony built on genocide and displacement, in this country that actively funds the occupation that stole Mohammad Bhar’s life, if Muneer or someone else I love would be next. Then it happened just a 15-minute drive from my house.

It’s been a month since Liam was taken. 595 days since Mohammad Bhar’s murder. And 78 years of my Palestinian family wondering when their kin will become the next victim of the occupation and genocide.

When I saw the now-viral image on January 20th, I called him “bunny boy.” He looked like Muneer when he was about the same age, tanner, and in a blue bunny hat. Racists said he was “asking for it” by simply existing, by going to school rather than staying burrowed in a basement to avoid being snatched and imprisoned. Little boys dressed like a prey animal get treated like one.

I couldn’t save bunny boy from being taken by ICE agents, but I saved his picture in my phone gallery—the blue-knitted hat with white ears, the Spiderman backpack, his scared but brave face. Carrying his photograph near my heart was the closest thing to asylum I could offer; he looked like someone I had vowed to protect.

His name is Liam Conejo Ramos and he is five years old. I called him bunny boy as reports trickled in that he and his father were en route to El Paso, Texas. I prayed he wouldn’t become another dog boy. His name is Liam Conejo Ramos and he was one of the seven students from Columbia Heights school district detained by ICE.

His name is Liam Conejo Ramos and he was used as human bait just like everyone who looks like Mohammad and my brother have been made to be for decades upon decades. His name is Liam Conejo Ramos and no head of plush could save him from being treated like a human animal.

I wanted to wail when his picture began to circulate, but I didn’t ask “how could this happen?” because I knew exactly how it happened, how it’s been happening, and how it always happens to those with melanated skin. I wanted to scream not just for Liam, but for the over 3,800 American immigrant children and more than 600 Palestinian children detained by ICE and the IDF, respectively, in just one year. I wanted to shout out to all who ignored decades of US-sponsored occupation here and abroad, “Can you hear us now?”

As a Palestinian American, I’ve lived in Minneapolis my whole life though vicariously in Palestine through my family’s stories. Now my hometown in Minnesota is experiencing the scourge of occupation in a way nobody should ever have to. On the day Liam was kidnapped, I held my brother close and prayed that he wouldn’t be taken, the same way I held him when I heard about Mohammad Bhar’s death, how he was left for dead. When his family was finally allowed to return to their home on Nazaz Street, they found Mohammad alone on the ground, his body covered in worms. I held Muneer in a way that was so familiar to me that it didn’t faze me anymore; I prayed I’d never grow desensitized to death.

But it’s only natural that I would—that we would. My Palestinian family are no strangers to being treated like human animals, whose mere existence is a crime. “Human beasts,” the Israeli Defense Minister called our people. We are savages needing to be put down, humiliated, caged. Prior to emigrating from occupied Palestine in the 80s, my family lived a life of enclosures and shackles. Armed soldiers patrolled in droves, spreading hate and fear everywhere, blindfolding children, pointing guns, gawking, spitting, laughing at us like animals in the zoo. At any moment, we could be corralled in a mass detention sweep, bound and raped and maced and mauled for committing the crime of simply existing on our land.

When I drive to work, I pray that the 3,800 other American immigrant children and 600 Palestinian children who are detained can come home as Liam Ramos did.

Recently on my father’s way to work, he nonchalantly asked for his passport while casually taking a phone call. To him it’s just as routine as the way he used to carry his Palestinian color-coded West Bank ID to travel from his home to his neighbor’s house at the end of the road, less than a block away.

“Baba, there were ICE agents at that restaurant the other day. It’s not safe to go,” I tell him. But Baba’s streets were crawling with ICE proxies during his entire childhood. Soldiers were as ubiquitous to him as mailmen. He laughs about the time he got punched by an IDF soldier, and the other time he, a teenager, hid behind a trash can to avoid being murdered by one. Raids are dinner table conversation in a way that is both horrifying and reclamatory. “Nothing new, I have my passport. I’ll be fine,” he says. I know he won’t be since none of us are fine, but for him, being fine in the face of occupation is all he knows to survive.

On my way to work downtown, I solicit advice from family members in the West Bank about how to deal with potential teargassing. I tell them, “This isn’t like the one they used during the George Floyd uprising—I hear this one feels like glass piercing your skin.” My cousin laughs, empathetically but pityingly, “Yes, I know that one. That’s the one they use on us here.” This is the kind of violence we’ve been screaming about to the world for almost eight decades.

It’s been a month since Liam was taken. And 595 days since Mohammad Bhar’s murder. And 78 years of my Palestinian family wondering when their kin will become the next victim of the occupation and genocide. It’s been a lifetime of wondering when the sheltered American consciousness, that ignored America’s support for occupation, will finally wake up because nothing about this occupation is remotely unprecedented.

The US was founded on the mass displacement of Indigenous Nations and has maintained its hold on power through countless acts of quasi-legal cruelty: the Black Codes, which tracked and restricted the movement of freed Black men immediately after the Civil War; the Chinese Exclusion Act, which denied entry to Chinese laborers and made permanent aliens of those who’d already sacrificed their bodies to American expansion; the internment of Japanese Americans, which stripped US-born citizens of their Constitutional rights; all of the mass deportations since ICE’s founding in 2003, the family separations and children in cages; and, of course, the US’s ongoing funding of the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Occupation, it is clear, is as American as apple pie.

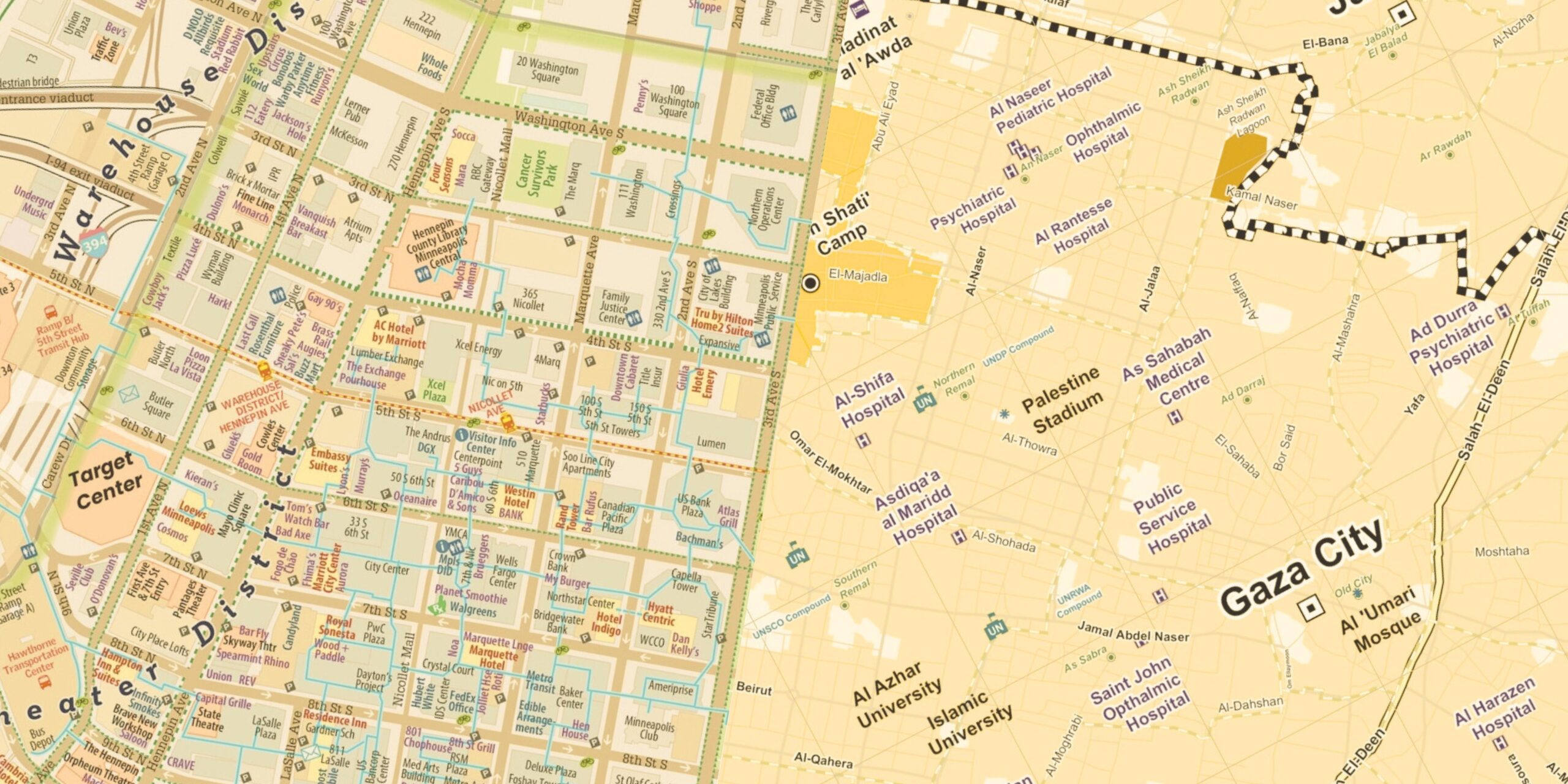

ICE agents actively train with the Israeli military and have a longstanding “counterterrorism partnership,” the kind of relationship that renders a snapshot of my father’s neighborhood in Hebron and the daily life we’ve witnessed for over two months in Minneapolis nearly identical.

This morning, on my drive through Minneapolis, there were no ICE agents that I could see, but I still held my breath. Although we’ve been told by federal and local officials that they are gone, they are still everywhere. Their victims and their proxies—US militarized forces and legacies—are all around us.

Passing unsheltered Indigenous folks standing with signs on corners, I wonder how many of them were swept up from encampments just a few months earlier by law enforcement who dare to police where the native inhabitants of this very land can reside. Gentrified neighborhoods displace Black and brown communities just as aggressively as ICE does, although with a polite smile. Universities invest in Israeli weapons companies used by both ICE and the IDF. Gated communities shelter impoverished enclaves, the legacies of decades of redlining right in our vicinity, redlining of the ostensible “good old days.”

When I drive to work, I pray that the 3,800 other American immigrant children and 600 Palestinian children who are detained can come home as Liam Ramos did, and I wonder, as I did in July 2024, “Who will be next?”

I return home to hug my sweet Muneer in the aftermath of national relief, the false relief that “the occupation is over.” I know to hold him extra tight in this home that isn’t our home—in this home that has to be our home because occupation stole our lives in Palestine. I hold him close, as the occupation rages on, only this time, quietly, just below the surface. I’ll never know when I’m holding my puppy boy for the last time.

Sana Wazwaz

Sana Wazwaz is a Palestinian American writer and theater artist. Her work appears in Black Warrior Review, Water~Stone Review, Hayden's Ferry Review, The Ghassan Kanafani Anthology, Overtly Lit, and has been featured at the Colorado College Fine Arts Center’s Muslim Futurism exhibit. Sana is a two-time member of New Arab American Theater Works’ National Playwright Incubator Program where her play, "Birthright Palestine," was developed and will be presented in the 2026 Festival of New SWANA Plays. Her work has been nominated for Best American Essay 2025, and was a finalist in Palestinian Youth Movement’s 2021 Ghassan Kanafani Arts Competition, as well as Black Warrior Review's 2025 Creative Nonfiction Contest. She holds a BA in English (creative writing concentration) from Augsburg University. Learn more at sanawazwaz.com