Letter From Minnesota: “A Prayer Must Be More Than Asking”

Kawai Washburn on Doing the Work Even in the Face of the Abyss

I would like to speak here briefly about car bombs, because I have seen one once, and I never want to see one again. A car, when detonated, becomes a scorched knot of metal, jagged with the last of its own glass and plastic, sentinel and quiet but somehow still containing both the initial concussion and—if you listen closely enough—the infinite lives of everyone it must have touched before it was finished. The car bomb I saw was in a museum in New York City, at the height of America’s second invasion of Iraq, and standing next to the car bomb was an American soldier, returned from deployment, who talked about what he’d experienced.

What he’d remembered more than anything when he returned to America, the soldier said, was getting on the subway for the first time and seeing all the people around him chattering about the restaurant they were going to, what movie they had just seen, which playground their children would go to after class, while he had just been living where the car bombs were, could in fact still hear the snap of bullets passing close to his skull, and there on the subway car, facing that difference, the soldier was plunged in an angry, lonely abyss.

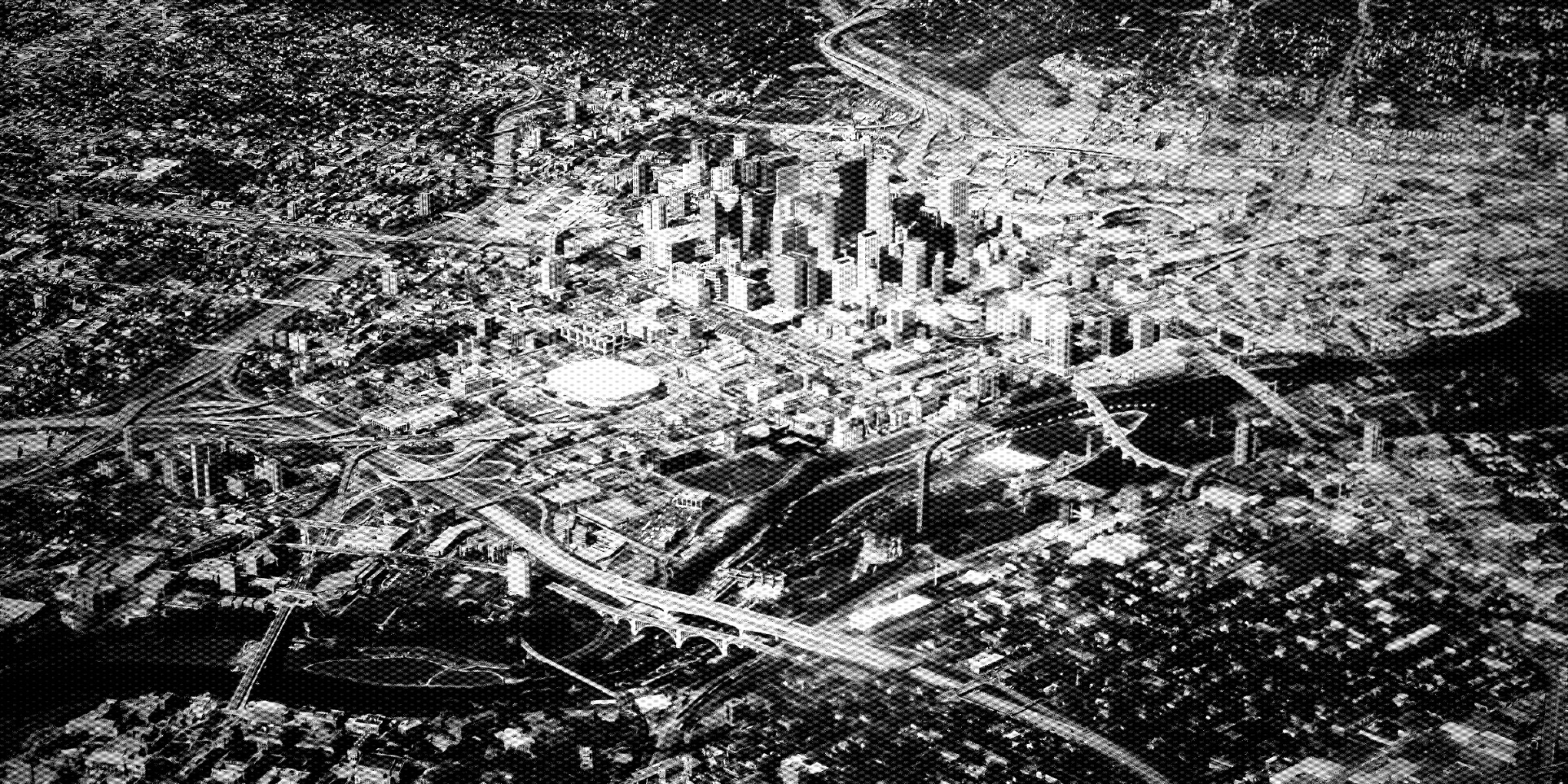

At the time that I was listening to his story, I had no idea he and I would ever have anything in common. But now my mouth, like his, is often pressed into an empty, angry line when I hop on a call with the voices of my neighbors and move about the city in my car, in the darkness, or on foot, in the morning, trying to locate the armed federal agents invading our Minneapolis. I can see warmth and incandescence through the curtains of the homes I pass, I can see the packed restaurants—sometimes I’m even the person inside those places—and yet when I’m out on the street, I, too, am at the bottom of an abyss.

For those hours in my car, or on foot, I’m in a world where unidentified and masked agents from the Department of Homeland Security swarm our Minneapolis in their tinted, caged vehicles, replete with tactical gear and assault weapons. They smash car windows and yank out drivers, they hustle solitary women from bus stops into cramped prison cells at midnight, they prowl around schools and daycare facilities and restaurants, hunting anyone with dark skin or a second language, or any other hint of what they’ve decided needs to be purged. Three agents in tactical gear abducting someone from a vehicle on the following intersection at 3:25pm, observers please, a voice says on a call. Confirmed ICE vehicle spotted at this intersection at 6:55am, idling near school pick-up, the text goes out. Cars converge on the locations, observers arrive on foot. The whistles, the cameras. Often there is nothing when we arrive—no agents, no victims—nothing but that presence, the same as a detonated car bomb, of all the lives that were touched by the time the agents were done.

Another weekend I’m in the stifling basement of a civic center with a room full of school parents, where we practice what to do if agents arrive at our local schools, churches, parks. We take turns roleplaying the parts of everyone involved: we scream and agitate as angry neighbors ready to throw snowballs, we bellow and stomp as agents preparing to assault and abduct, we prepare to be the ones in the middle, trying to bring everyone down, to try and keep everyone—especially the children—safe.

None of us are qualified to coordinate a citywide effort to resist a heavily armed and federally-sanctioned squad of sociopaths, unleashed with total impunity upon everyday citizens.

In the middle of one of these melees—everyone is doing a good job playing their parts, it feels like a truly violent and threatening scene each time we practice—one of the women in the group reaches out, palms open like a prayer, to the person screaming at her. She says something direct and quiet and the person stops making noise, suddenly they are holding hands, even as everything around them collapses into combat.

Later, debriefing the training, we all remark on that moment. We asked the woman—silver-haired, small in stature but so calm and warm, so strong—what she said. “I told her I was so happy she was here,” she says. We asked her how she knew to say that, how she knew it would work, how it would make the agitator calm down. She merely shrugged. “I’m a teacher,” she said. “It’s the same thing I would have said to any of my students.”

I’m so happy that you’re here. I keep coming back to that, in the weeks after, weeping in my car, weeping on the street, weeping in my home. Aren’t those the only words any of us want to hear, at any moment in time? When she said it her palms were up and close, as in a certain type of prayer. The writer Jason Reynolds gave an interview in NPR recently, where he described taking care of his ailing mother, bathing her and helping her dress, recognizing her as a vessel of life, once that had carried him and now emptying out, and how he would be there for her, every last drop of her life, and how that was a sort of prayer. “…a prayer can’t just be asking, right?” he said, and I know he’s correct.

I know Jason is correct because I work a three-hour shift in a makeshift food distribution facility, wrapping up box after box of food and diapers and infant formula to be delivered to all the families too scared to leave their homes now, my breaths and those of all my hustling neighbors around me blooming white like flowers in the bitter cold, and when I’m done packing my back is aching and I don’t know that anything is better but I will do what I can to feed the people now that, for so long and so many ways, have fed me; I know Jason is correct because I walk, one foot in front of the other, across this block or that, phone in my pocket and the voices of my neighbors in my ears as an agent appears here, and here and here, and we arrive; I know Jason is correct because I practice how to lock arms with neighbors I didn’t know until mere hours before, and we whisper encouragement to each other as we prepare for the tear gas and pepper spray, the broken glass and projectiles.

Some days when we’re in the same room together, we neighbors talk about how overwhelming it all is. How could it be anything but? We aren’t professional protestors, whatever those even are. We are administrative assistants, middle managers, social workers, nurses, retirees, accountants, advertising executives. Two months ago we were organizing bake sales for local churches, shepherding students to spelling bees, and coordinating carpools for hockey games. None of us are qualified to coordinate a citywide effort to resist a heavily armed and federally sanctioned squad of sociopaths, unleashed with total impunity upon everyday citizens.

In doing this work I spend so much time in the abyss, as the soldier did, alone with the difference between the world that exists if we are far away, only watching, and the world that exists if we come out into the streets. I pack boxes and join calls and walk streets and feel myself inside clouds of gas and chaos, wanting only to reach my hands out, palms up, to everyone in this beautiful, flawed city, us neighbors from all over the world, here for a better life that’s now under attack, I want to hold my palms up, as if in prayer: I’m so happy that you’re here.

Don’t ever go.

Kawai Strong Washburn

Kawai Strong Washburn was born and raised on the Hamakua coast of the Big Island of Hawai’i. His first novel, Sharks in the Time of Saviors, Won the 2021 PEN/Hemingway award and the 2021 Minnesota Book Award. Former US President Barack Obama chose it as a favorite novel of 2020, and it was selected as a notable or best book of the year by over a dozen publications, including the New York Times and Boston Globe. His second novel, The Names of the New World, will be published in fall 2026 by MCD x Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Washburn lives with his wife and two children in Minneapolis.