Letter from Minneapolis: Why the Rebellion Had to Begin Here

Su Hwang on Generations of Activism Standing in Opposition to Racism

Like so many of us, after two months of quarantine, I often wake up not knowing what day it is.

*

Memorial Day weekend came and went unceremoniously, I thought, until disturbing headlines peppered my newsfeed the next morning: the Minneapolis police had killed another Black man. At the intersection of Cup Foods and a Speedway gas station, a mile or so up on Chicago Avenue where I currently live––George Floyd’s life was extinguished over a contested twenty-dollar bill. Twenty fucking dollars. And like many, I didn’t have to watch the viral video to know what went down. Sadly, a lot of us in the Twin Cities know this script all too well after the deaths of Jamar Clark, Philando Castile, and countless others without hashtags. The screenshot of Derek Chauvin’s knee on George Floyd’s neck as he lay handcuffed on hot asphalt was all I needed to see to know that this was another egregious, violent, racist act perpetrated by the MPD.

And yet the tenor was different: this white cop’s smug mug, his hands shoved in his pockets as if he didn’t have a care in the world, the sheer audacity of his hate. It didn’t matter it was still light out. It didn’t matter he was being videotaped. It didn’t matter there were bystanders, many of them begging for him to stop, to show a little mercy. It didn’t matter there was a global pandemic. It didn’t matter that George Floyd called out for his late mother. To Chauvin and the other three officers, a Black life didn’t matter enough, which in effect made their own lives not matter, because they were willing to risk it all. Nothing mattered because they truly believed they were going to get away with murder.

*

I’m not a native Minnesotan, but South Minneapolis has been my home for the last seven years. By most standards, I’m still a relative outsider, a transplant, so I must acknowledge that I am hardly the definitive voice on all that is happening here––just one in a kaleidoscope of perspectives. (I suggest you read Danez Smith’s incredible commentary in the New Yorker, GeNtry!fication by Chaun Webster, and the anthology A Good Time For the Truth, edited by Sun Yung Shin, to start.)

Having grown up in New York then spending much of my adult life seesawing from there to San Francisco and Oakland, I was an insufferable, bicoastal snob when I first arrived in the Twin Cities. Back then, I complained a lot about seemingly endless winter months, shoveling so much snow, feeling landlocked, Minnesota Nice. As an Asian American woman, I had trepidations about living in a flyover state because race is a constant companion I travel with, as it is for so many of us, and I really had no idea what to expect in the land of 10,000 lakes. I knew this was a super white place, and vowed to return to the west coast as soon as I was done with my MFA program. But then the socio-economics of the Bay Area became untenable for a forty-something poet like me, and perhaps more surprisingly, I found community here. For the first time in my wayward life, I began setting down roots.

*

Stunning sight on the sixth day of protests: a sea of people from all races and walks of life flooding both sides of the I-35W bridge on a sun-drenched afternoon (incidentally, the same bridge that collapsed into the Mississippi River in 2007). Momentum only seemed to grow as the crowd swelled in the thousands when suddenly from the bottom of my computer screen, a tanker truck barreled down the roadway, cleaving the crowd in half like a broken zipper. Nothing short of a miracle that no one was seriously hurt, the truck driver, who has since been released, was pulled out of the truck and beaten by a handful of protesters (and magnanimously protected by other protesters) until he was placed in custody. I had immediate flashbacks of the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, having watched a similar scene unfold on television as a teenager––it was hard to ignore the eerie echoes.

Almost 30 years ago, four white LAPD officers were acquitted of brutally beating Rodney King, captured on video and aired around the world long before iPhones and social media. I watched live broadcasts of widespread protests, violence, fires, and civil unrest mostly in and around Koreatown, where dozens died and thousands were injured or arrested. What many may not know is that a year before, a Korean store owner shot and killed a Black ninth-grader named Latasha Harlins, who she suspected of shoplifting, and was only sentenced to probation and community service. This case was the exclamation point in a long chain of vitriolic, often deadly volleys between Korean merchants and those within the Black communities that they served. Cultural biases and language barriers as well as stark economic disparities fueled distrust and blame from both sides, but these issues did not crop up in a vacuum or manifest out of thin air.

Sadly, a lot of us in the Twin Cities know this script all too well after the deaths of Jamar Clark, Philando Castile, and countless others without hashtags.

Now retired and living in Southern California, my Korean-immigrant parents used to own a cramped corner store in the Queensbridge projects in the shadows of the Manhattan skyline at the time of the Riots. They sold and set up pagers, batteries, baseball caps, t-shirts, handbags, and toys, among other knickknacks. When I helped out during summer breaks, I was tasked with copying keys on the old screeching machine and getting lunch next door from the Chinese takeout place with thick bulletproof glass coated in grease.

Much of my debut collection, Bodega, was inspired by this place and period; and there, the realities of life for Black Americans came into very clear focus for me. White cops patrolled the area around the clock, but they never made anyone feel safe. They were uniformed bullies on the prowl, and it was abundantly clear they only cared about protecting and serving whiteness. Sirens were a constant fixture as were the undercurrents of deprivation, desperation, fear, and grief brought on by centuries of systemic racism and abject poverty.

My family experienced discrimination and prejudice, yes, and dished it back, yes, but nowhere on the scale that the police and other white monoliths have and continue to inflict on Black communities all across the United States. And in our attempt at white adjacency to achieve the myth of the “model minority,” however subconsciously or explicitly, my family was complicit in anti-Blackness too. White supremacy, whether internalized or not, pervades every interaction within marginalized communities in this way, pitting one ethnic group against another so we can, in essence, cancel each other out.

It wasn’t always an us versus them situation by any means, but then again, white supremacy doesn’t allow for nuance. What wasn’t being told on the nightly news was that my parents had regular customers they knew by name, their preferred brands of this or that, and their individual stories. In return, they were affectionately known as Suzy and Mister H. by many members of the community. They shared jokes, mostly through hand gestures because my parents barely spoke English. I witnessed countless acts of kindness and mutual respect from both sides of the counter. And by virtue of our corner store having high elevated counters and windows chock full of merchandise, my parents offered sanctuary to many young men selling the occasional dime bag or whatever. Even in this fraught, urban food chain of have and have-nots, there was also a kind of intimacy––an unspoken camaraderie of doing our best to survive and thrive. When many Korean-owned businesses in Los Angeles burned to the ground, my parents’ store on the other side of the country remained unscathed, for protection went both ways.

Seven years after the LA Riots, a 23-year-old Guinean immigrant named Amadou Diallo was killed in a hail of 41 bullets in front of his apartment building in the Bronx. Four plain-clothed NYDP officers were later acquitted of executing an innocent man walking home from dinner because he vaguely fit the description of a suspect. What they claimed was a gun was Diallo’s wallet.

*

As a late bloomer to poetry, landing in Minnesota has been a blessing in a multitude of ways. Minneapolis is a world-class literary hub, the arts funding here is best in the country bar none, and as far as I can tell, you can’t throw a rock without gently tapping a brilliant and inspiring BIPOC/LGBTQIA/white-ally writer, artist, musician, dancer, elder, educator, arts administrator, filmmaker, scholar, curator, grassroots activist, healer, hospitality worker, civil servant, and social justice warrior, or sometimes a combination of these––many of whom I call my friends, mentors, and colleagues. There are strong, multi-generational Somali and Hmong refugee communities as well as the highest concentration of Korean adoptees in the country. Minneapolis and St. Paul politics tend to err on the progressive side compared to other major US cities, but like every state in this country, Minnesota has a very dark, sinister side.

First and foremost, we occupy stolen Dakota and Ojibwe land, and the largest mass execution in US history occurred in 1862 when 38 Dakota men were publicly hanged in Mankato. On June 15, 1920, exactly a hundred years ago in Duluth, three Black men named Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, who were wrongfully accused of rape, were taken from jail and lynched by a white mob of thousands. Since then, government officials and shady developers have sanctioned the destruction of predominantly ethnic neighborhoods for white capitalistic agendas, reinforcing a passive-aggressive culture of exclusion and double standards. Fast forward to the present: Minnesota ranks second in the nation for worst median income and homeownership gaps between white and black residents, and is 45th out of 51 states when it comes to racial integration––making it one of the most segregated states in the entire country. The MPD continues to kill Black Minnesotans at an alarming rate and with total impunity because of unapologetic racists at the top like Bob Kroll, president of the police union, and Hennepin county attorney Mike Freeman. Don’t even get me started on incarceration rates for people of color in Minnesota. And as of last year, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, there were at least twelve known hate groups operating within state lines. To gain more historical context and clarity, please read this and this.

From the outside looking in, the depth and breadth of these sweeping changes may seem radical in their swiftness, but they are the result of decades of community-based activism.

Many white Minnesotans are married to this squeaky-clean image of bike-friendly paths, the home of Prince, pristine parks, Swedish meatballs, cheese curds and hotdish, and pontoons on shimmering, cabin-dotted lakes befitting those “The Best of” lists that get published every year, but the reality is far from these sanitized archetypes. High quality of life in this country has always been colonial and conditional. Finally, the fragile white veneer of Minnesota Nice has been hammered into a million pieces with the world as witness because this nebulous sense of fake politeness and notions of not wanting to rock the boat are just as detrimental as overt hostilities against people of color. If Minnesota were a person, I’d imagine the Amy Coopers of the world would fit the bill, and Chauvin’s knee is the final line in the sand––you are either on the right side of history or you will be left behind.

In light of all these deep-seated issues, there seems to be a shift in energies. People are finally waking up, some forcibly so; it’s hard to look away when there’s an enormous conflagration on your street, the literal burning down of centuries of apathy, willful ignorance, hoarded privilege, and misplaced entitlement. Days after George Floyd’s murder, the University of Minnesota, MN public school system, and the Department of Parks and Recreation have cut ties with the Minneapolis Police Department. In addition, the state of Minnesota has filed a civil rights lawsuit against the MPD, and the Minneapolis City Council just made a pledge to a huge crowd at Powderhorn Park that they will begin taking concrete steps to disband the police, thanks to grassroots organizations like MPD150, Black Visions Collective, and Reclaim the Block.

Meanwhile thousands of citizens continue to fill the streets to protest, mourn, clean, paint murals, and plan for a better future. Even at the height of violence and raging fires, the majority of which were intentionally set by white supremacists––huge, diverse crowds spontaneously gathered at numerous sites with brooms and buckets to assist in the aftermath, day after day after day. Bleary-eyed, over-caffeinated bands of neighbors and community leaders continue to come together to offer mutual aid, mobilize supply drop-offs, and organize neighborhood patrols. In the embers, something truly beautiful seems to be coming to life.

Let’s be very clear: Minneapolis and St. Paul, so-called bastions of white liberalism, are under attack. We are in the crosshairs of boogaloos and other rogue white nationalist maniacs looking to fan hate and fear, but what they don’t realize is that legions of lovers and fighters have been laying the groundwork toward resistance and true equity for generations. From the outside looking in, the depth and breadth of these sweeping changes may seem radical in their swiftness, but they are the result of decades of community-based activism by BIPOC individuals, collectives, and organizations working tirelessly to dismantle white supremacy in Minnesota for a very long, long, long time. Also, youth movements including nonprofit media collectives like Unicorn Riot have been instrumental in disseminating the truth. So, as much as we ache for the destruction of cultural landmarks and essential businesses in our backyards––the traumatic toll yet to be fully processed––groups of visionary artists, civil servants, activists, healers, and builders are already on the scene. They’ve been here all along.

*

Many are calling this an “inflection point” in American history, including myself, but the more I think about it, the less it holds water. Inflection implies singularity, of one musculature or a single stream of consciousness, when there have been multiple inflections since the looting of this land from Native Americans to the founding of the country on the backs of Black lives. I believe we are truly at a point of convergence. Convergence or confluence implies multiplicity and cumulativeness––a cacophony of voices and perspectives. In this distinction, we honor the lingering ghosts of all our ancestors. We can no longer afford pivoting from one point to another and call it progress or justice––the weight of our collective histories can no longer support these blatant disparities. What we’re seeing and experiencing is a cavalcade of centuries of protest, of deaths and rebirths, the final heave for human decency for all.

Even in this fraught, urban food chain of have and have-nots, there was also a kind of intimacy––an unspoken camaraderie of doing our best to survive and thrive.

And yet we are still in the throes of a global pandemic, and as an Asian American woman, the current backlash against people who look like me clearly demonstrates that people of color are always at risk from the insidious exclusion of the white supremacist gaze. K-pop fans crashing hate-filled hashtags and calls by Asian American organizations and individuals to support Black Lives Matter bring me solace––making amends for the many years we participated in anti-Blackness––but there is so much more work to do. White supremacy and white complacency can’t hide anymore. There is no longer the cloak of night to reason away truth. Cameras are rolling. Every marginalized human is exhausted and fucking pissed. The global pandemic has disproportionately affected Black and brown communities, but this virus has proven to be the great equalizer in many respects, showing 99% of us that we are not immune from the evils of capitalism or the ineptitude of those who are supposed to protect and serve the people.

*

George Floyd was a transplant like me; I’ll be 46 years old later this year. George was known as Perry or Big Floyd by his loved ones; some dear friends call me Su Bear. Like me, he made his way from Houston for better opportunities and started to set down some roots in Minnesota. He was working two jobs while building his community when the pandemic hit. He worked security at a restaurant, I’ve worked in hospitality for over a decade––we could have been co-workers, friends. George Floyd was murdered a mile up from where I live on Chicago Avenue, at the intersection I drive past every damn day. And just like any other Minnesotan, George Floyd had the right to complain about the weather and bad drivers who can’t merge for shit, eat cheese curds dipped in chocolate at the Minnesota State Fair, be photographed holding a humongous fish. George Floyd should have been able to wake up and not know what day it is.

*

This is not the first time I’ve seen buildings turn to ash. I was living on the corner of Grand and Lafayette Street on the cusp of Soho/Chinatown when I saw the second plane hit the Twin Towers on 9/11. I was late to work, a startup on Wall Street, because it was my turn to walk Ollie, the rescue dog my roommates and I adopted the day before. And as we huddled around the TV to figure out what was happening, we watched the towers fall from behind a screen. For weeks there were National Guardsmen stationed on every corner. Sirens were constant. I wore a facemask to work. There was a paradigm shift.

I feel it shifting again.

There’s a lot more to say, but my thoughts are in shards right now. My heart is broken for my city, for George Floyd’s family, for Breonna Taylor’s family, for Tony McDade’s family, for Ahmaud Arbery’s family, and the many other lives lost, but I also believe in goodness and the goodness of the people I know and love. So I will end this rambling missive with the prophetic words of an incredible writer, artist, goddess and friend, Junauda Petrus-Nasah from a recent Star Tribune feature with two other amazing souls, Michael Kleber-Diggs and Shannon Gibney: “Earlier, I had visited the memorial and felt so much sacredness, community love and peace, amid the aftermath of the inconceivable and public execution. Overnight, our city became a phoenix, glowing and rebirthing something unstoppable and irresistible for the world. On Dakota land, in the midst of a global pandemic, the wounds of white supremacy, oppression, police violence, erasure and parasitic capitalism caught flame. And amid the fire, grief, confusion and property loss, there was a transformation crystallizing.”

*

Black Lives Matter.

___________________________________

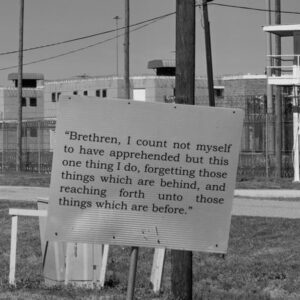

Photo: Chicago Ave. and E 38th St. in Minneapolis, Minnesota, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Su Hwang

Su Hwang is a poet, activist, and the author of Bodega with Milkweed Editions, which received the 2020 Minnesota Book Award in poetry. Born in Seoul, Korea, she was raised in New York then called the Bay Area home before transplanting to the Midwest. A recipient of the inaugural Jerome Hill Fellowship in Literature, she teaches creative writing with the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop and is the cofounder, with poet Sun Yung Shin, of Poetry Asylum. Su currently lives in Minneapolis.