Let's Talk About the Fantasy of the Writer's Lifestyle

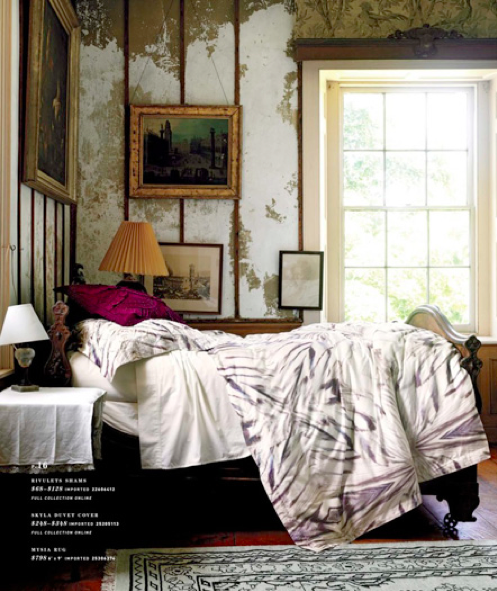

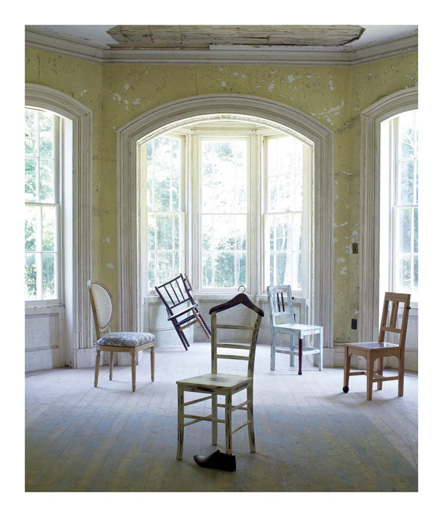

The Undying Trope of Glamorous Decay is Basically an Anthropologie Catalog

Let’s talk about the fantasy of the “writer’s lifestyle.” Most writers and most readers are familiar with the basics: the writer is typically an educated person of modest background who knows famous and wealthy people; the writer is an aloof guest at their parties. The writer keeps an irregular schedule, needs deep solitude in order to work, has dysfunctional personal relationships, and is not good for much except the brilliant prose they occasionally produce. Money is scarce, but the writer somehow always lives alone; the landlord is always angry, but the writer is never quite evicted. The writer spends a lot of time in cafes with huge, flaking mirrors behind the bar; even more time is spent in lofts and attic apartments, places with casement windows and creaking staircases.

The writerly apartment in this fantasy is bare and minimal; the walls are unpainted plaster, or the wallpaper is peeling; the heat is faulty or not there; there are books stacked on the floor. It looks this way because it’s Paris struggling out of the deprivation and destruction of a world war, or New York soldiering on through the Depression, living in the wreckage of 1920s glamor. The writer spends hours in cafes, working and drinking, because the cafes are heated and the apartment is not. The aesthetic of this fantasy is permanently frozen in the first half of the 20th century, in the cities (and occasionally the beach resorts near cities) of Europe and the United States. The reason the fantasy writer lifestyle is set in such a particular time and place is that the interwar and postwar American writers who went to Europe for cheap rents have exerted a massive influence on the American idea of what literature is. Who casts a longer shadow across American fiction and curricula than Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Baldwin?

While considering the specificity of these images, recently, something came to me: It’s an Anthropologie catalog.

For years I got Anthropologie catalogs even though I had never bought anything from them. I requested the catalogs from their website, and signed up again every time I moved. The catalogs are beautiful, and they gave me that slightly doubled feeling that you get, as a consumer, when you encounter marketing that understands your desires better than you would like to admit. You resent the presumption but are compelled by the material.

The girls of the Anthropologie catalog flit through a perpetually wrecked version of Europe; they lounge in decaying colonial hotels in the Caribbean and Southeast Asia. The war has always just ended. Stretched canvases lurk in the background. The settings are grand but derelict, suggesting that a quirk of history has made them available to you, the ordinary person. “This old place?” the Anthropologie girls say, gesturing at a ruined terrace overlooking the Adriatic Sea. “It’s falling apart, you can stay here for a song.”

That was the reality that Americans encountered in Europe after World War I. It’s easy to forget that Hemingway and the rest went to Paris because it was cheaper than staying at home, and that it was cheaper because a catastrophic war had just laid waste to the continent. These writers produced so much material about each other, in fiction and in letters, that they accidentally crystallized a specific time and place in the American imagination as the essence of what a creative life looks like. This was not only a setting: it was a particular economy. Not only was rent cheap, but print was still the king of mass media. It was possible, for a brief moment in time, to make a living selling pieces to magazines. As a result, the image of the writing life created in this period includes no non-writing day jobs whatsoever. Nobody teaches; nobody is a nurse or a bank clerk, a receptionist, a soldier. Writers write, and that’s it. They are free to keep odd hours, travel cheaply by rail, drink more than they should, and become overly involved in doomed relationships. No one has to get up in the morning.

“This fantasy image does us a disservice. It leaves us with no model to follow when we try to integrate art-making with functional lives.”

This aspect of the fantasy is present in the Anthropologie catalogs too. I challenge you to look at these catalogs and integrate the images presented with the notion of having a job in any conventional sense of the word. Now, you may be objecting. “What do you mean? Do you expect them to show people commuting in the clothes? Washing out the coffee maker in the breakroom? Wearing a headset?” I don’t, of course. But consider a point of comparison: the equally mighty J.Crew catalog. J.Crew also shows beautiful young women wearing their clothes, occasionally in lovely destinations, but there are fewer of these location shoots and more images of models on white backgrounds, which the consumer can easily project into her own day-to-day life. More importantly, J.Crew actually sells clothes that a person could wear to a job that is high-status enough to pay for said clothes: wool pencil skirts, silk blouses, tidy trench coats, most of it in subdued colors and prints. The photos of Palm Springs or wherever have the aspirational gloss of a nice vacation taken by a rising partner at a whiteshoe law firm.

Anthropologie girls, on the other hand, are loaded with beads, fringe, eyelet lace, and bright prints; their natural modes are the sundress and the cape. You could wear these clothes to work if you were a kindergarten teacher or a a choreographer, but in neither case would you make enough money to buy them. In January 2018, the landing page at J.Crew features a sheath dress called the “Résumé,” while the landing page at Anthropologie shows a woman in a fringed top and white shorts sitting in golden-hour light on some kind of ancient parapet. The brand presents the eternal bohemian enigma: so much travel, so much leisure, with no plausible gesture toward the making of money at all. Trust fund, the images whisper. Or, alternately: brilliant mid-century writer, paid so well that she is never pressed for time. She stops off in Trieste, files some copy at the Western Union office, waits for her money to be wired in, and gets on the train again.

This fantasy image does us a disservice. It leaves us with no model to follow when we try to integrate art-making with functional lives. That period when a person could make a living writing fiction for periodicals was a blip, and it’s over; we’ve long since returned to the baseline, which is that the vast majority of fiction is written around and beside a whole lot of other work, and it’s the other work that pays the rent. As such, there is no writer’s lifestyle; your lifestyle is determined by what that other work is. I’m baffled when I come across interviews where writers laughingly allude to the solitude, say, or the introspection of the novelist’s life. No matter how solitary or introspective you are while you’re writing novels, you are likely spending many more hours each week at another job, or commuting, or raising kids, or trying to keep your house clean. I spend more time on the subway each week than I spend writing, and I’ve written two novels.

Those of us who are lucky enough to be living this fairly obvious reality can feel at times like we’ve failed. I have the pleasure of my work, but where’s my glamor? Why doesn’t it look the way I thought it would when I was 14? The cruel edge on the bohemian fantasy is that it pretends that leisure can be had for free. As every adult knows, leisure takes capital. All that peeling paint and cracked tilework creates a convincing impression of accessibility, at least to the naive teenagers that many of us were when we first started to imagine what our future lives as artists would look like. But it’s an illusion, the result of almost a hundred years of an economic fan-dance in the popular imagination.

Still, there’s a pleasure in moving from fantasy to reality. The fantasy writer is a traveler and an outsider, perpetually passing through. She wanders in pursuit of material and stops for a time in places where other writers have gathered, like flocks of migratory birds. With no need for a regular job at a fixed address, the writer is shallowly rooted. The freedom is heady, but there’s a loss there too. The Anthropologie girl is never at home, unless she actually lives in that unpainted Scandinavian cabin with the reindeer in the yard, which seems unlikely, since she’s wearing a $300 sweater and suede shoes. She’s probably just visiting.

Setting aside the catalog fantasy means being able to interrogate the idea that the writer is always observing, standing at the edge of the party, never unpacking all his suitcases or renewing his lease. Most writers are, in fact, as deeply rooted in their communities as anybody else. But that’s hard to picture. We know how it feels, but what does it look like when the writer belongs to a health care workers’ union and is on the PTA? Has opinions about local taxes? Organized the repast when a neighbor died? How would it look if we pushed that rootedness to the center, valorized it, acknowledged it as the norm?

If I were speaking to my 14-year-old self, who had already fully assimilated the writer-lifestyle-fantasy from various sources, I would say this: First of all, good news. You’re going to write books. Second, you’re going to spend very little time on terraces or piazzas of any kind. There will be vintage tilework in your future, but it will be the lavender-and-black extravaganza of your circa-1986 bathroom in Queens. Your train travel will mostly take place on New Jersey Transit, which is nothing to sneeze at if you’ve ever enjoyed the views over the swamps of Secaucus, or criss-crossing the Delaware River on the way to Philadelphia. There will be cafes with huge flaking mirrors, because this is New York, but you won’t linger in them long because all the tables will be taken by people on laptops. When you stay up too late and sleep through your writing time, it will be because you were watching Bob’s Burgers online, not carousing with jazz musicians. Carousing will lose most of its appeal when you move to a train line that goes local after 10:30 pm. The important thing is, though, that you will get to write.

Rosalie Knecht

Rosalie Knecht is the author of Who is Vera Kelly?, Vera Kelly is not a Mystery, winner of the Edgar Award, G.P. Putnam’s Sons Sue Grafton Memorial Award and a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award, as well as a Relief Map, and a translation of Aira’s The Seamstress and the Wind. Vera Kelly Lost and Found is her latest novel. She lives in Jersey City, NJ.