If I concentrate, I can see where the river should be. It almost doesn’t exist, like the blue of skim milk. Or tailor’s chalk I’ve watched Dox brush away after sealing a stitch. But I know it’s there. The river waits for me, and that’s all that matters.

*

My father shuts off the engine. The pickup rattles. We sit and stew. After a bit, we can smell the random field. It’s been torn open, that’s what I say. My father winces. In my head, he corrects me: “Aspire to precision, Pearl.” When he talks this way, I feel like he’s gone back in time, like I’m one of his students being forced to listen to him.

*

“Pearl,” my father says now but doesn’t say anything else. It means get out. It means, at the very least, get a handle on the dog. Marianne Moore is off the pickup and jumps the grass ditch. Though the dog has bad hips, she is doing smooth ovals, making a dirt necklace in the open field. She is smiling.

I slam the truck door. There’s a tinny ring, even though the sides are mostly rust and primer. I grab a shovel and some rope from the back. There are mouth-sized holes in the truck bed. Marianne Moore hunkers down like she’s already been shot.

*

My eyes follow where the rows of broken earth head north. They end on the spongy loam. From there mix gaps of pale sky and lit leaf canopies the amber of fresh motor oil. The river is just on the other side of those trees. It’s a smear of acrylic. On the river’s surface float plywood skiffs and other vessels of scrap wood.

For the last few years I’ve had no choice but to become someone else. I’ve been around these kinds of boats, these quick creations. Sterns weighed down with piecemeal outboard motors, the shells endlessly dented out of frustration. Metal casings entirely removed. The dampened guts of tinkered-with chokes puff, held open by paint-coated screwdrivers and pastel pink putty.

Everything is makeshift.

*

My father reaches behind the bench seat, unzips one end of the leather case I’d sewn for him myself, Dox having been good enough to show me how on a scavenged sewing machine. My father pulls out the shotgun like he’s unsheathing a sword. He breaks the gun’s neck and checks the empty barrels out of habit.

“My father has become the kind of man who likes to wear a vest without a shirt. He is ripe and smells like what I remember of store-bought spices, back when my mother used to do all the shopping.”

He picks up a crushed box from the floorboard and shakes it, then slips into his suit-vest pocket the last of the shells, lipstick red and the size of quartered candlesticks. His vest is a light blue pinstripe. It’s a miniature of the tilled field, a riffle where the river shallows.

*

My father has become the kind of man who likes to wear a vest without a shirt. He is ripe and smells like what I remember of store-bought spices, back when my mother used to do all the shopping. He’s a dank mixture of cumin and turmeric, if I’m trying. His graying hair reaches past his shoulders. I turn my head the moment I see his nipples peek out from the sides of the vest. His nipples are brown and wrinkled like pecan meat.

*

“You ready?” he says.

“I think so.”

“Either you are or you aren’t.”

“Okay.”

“Precision, Pearl.”

“I’m prepared to do this one thing that will make you proud of me.”

“That’s better. That’s my girl.”

“How come we have to do this?”

“Because she should’ve been put down a long time ago.” I let that sit out there for a bit.

“Pearl?”

I try to nod.

*

I hate when he calls me his girl. Not because I can’t be anyone’s girl, but because if I’m anyone’s girl, I’d have to be his by default. I’m trying to make peace with this idea. It’s been getting more difficult. The more I catch glimpses of what kind of man he really is.

*

Marianne Moore curls up the size of an alligator snapper, or one of those antique circular hatboxes I’ve found in one of the hallway closets of the boathouse. She waits for us in the dirt. I could kick her where she is and send her rolling between the rows. Sometimes I want nothing more than to let her have it. Don’t get me wrong, I love her, but I can’t help thinking about how that would look, the dog on her back like a flipped turtle, with her legs going through the motions all herky-jerky.

*

My father and I walk the field. I carry the shovel. There’s a skin of rust on the shovel’s head. It’s been put to the test a time or two. My father cradles the shotgun in the crook of his arm. In these moments, it’s as if he’s bought into this new life—hook, line, and sinker.

*

In the air of the open field there’s the tang of gun oil my father wiped over both barrels. I hold the shovel in one hand and the splintered rope in the other. If I squint like my father, the rope is a single line that leads to Marianne Moore’s neck.

“Princess,” I say, and the dog smiles back, I swear. Like sweet Dox, she has lost most of her teeth. My father calls it a survivor’s smile. Whatever it is, it’s painful to take note of.

*

“This is for her own good,” my father says.

I know it, though I don’t let on.

He wants me to put the dog out of her misery, but instead, I’m going to turn her body into lace.

__________________________________

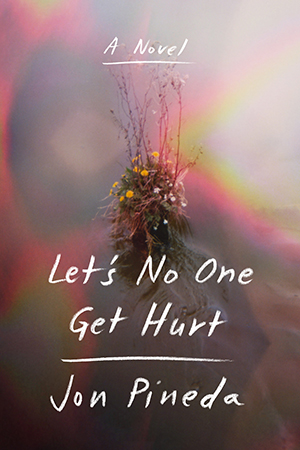

From Let’s No One Get Hurt. Used with permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2018 by Jon Pineda.