Here’s every winner of the National Book Award for Fiction and Nonfiction during the 21st century.

Dust off your formal wear and break out the bubbly because the National Book Awards (a.k.a. the Oscars of the book world) are nearly upon us. Yes, in just a few short hours, five dumbstruck authors will be fêted, garlanded, and welcomed into the American literary pantheon.

For those of you who’ve never heard of the National Book Awards, allow allow us to elucidate: every Fall the National Book Foundation nominates twenty-five books across five categories (Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, Translated Literature, and Young People’s Literature) with the winners being announced at a glitzy November ceremony in New York City (or, in this year’s case, online…again…sigh…).

Now in their 72nd year, the awards are considered by many to be the country’s most prestigious literary honor, and have, in times gone by, been won by such titans as Ralph Ellison, William Faulkner, Saul Bellow, Flannery O’Connor, Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, Annie Proulx, Susan Sontag, and Colson Whitehead, to name but a few.

As we await the announcement of this year’s winners, here’s a list of the forty-one previous fiction and nonfiction honorees of this still-young century

*

FICTION

2020

Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu

(Pantheon)

There are a few years when you make almost all of your important memories. And then you spend the next few decades reliving them.

“One of the funniest books of the year has arrived, a delicious, ambitious Hollywood satire … This stripped-down format is the perfect delivery system for the satire of Interior Chinatown. Ridiculous assumptions pop … While sticking to the screenplay form, Yu bends it enough to go deeper—long descriptive passages become mini short stories … Like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern from Tom Stoppard’s famous play, the characters see and comment on the artifice of their creation … It’s mind-bending storytelling, not easy to pull off. Yu does it with panache.”

–Carolyn Kellogg (The Washington Post)

2019

Trust Exercise by Susan Choi

(Henry Holt & Co.)

Thoughts are often false. A feeling’s always real. Not true, just real.

“Choi’s new novel, her fifth, is titled Trust Exercise, and it burns more brightly than anything she’s yet written. This psychologically acute novel enlists your heart as well as your mind. Zing will go certain taut strings in your chest … Choi gets the details right: the mix tapes, the perms, the smokers’ courtyards, the ‘Cats’ sweatshirts, the clove cigarettes, the ballet flats worn with jeans, the screenings of ‘Rocky Horror,’ the clinking bottles of Bartles & Jaymes wine coolers … Choi builds her novel carefully, but it is packed with wild moments of grace and fear and abandon. She catches the way certain nights, when you are in high school, seem to last for a month—long enough to sustain entire arcs of one’s life … The plot fast-forwards about 15 years. Minor characters become major, damaged ones. I do not want to give too much of this transformation away, because I found the temporary estrangement that resulted to be delicious and, in its way, rather delicate.”

–Dwight Garner, The New York Times

2018

The Friend by Sigrid Nunez

(Riverhead)

Your whole house smells of dog, says someone who comes to visit. I say I’ll take care of it. Which I do by never inviting that person to visit again.

“I don’t know whether or not The Friend is a good novel or even, strictly speaking, if it’s a novel at all—so odd is its construction—but after I’d turned the last page of the book I found myself sorry to be leaving the company of a feeling intelligence that had delighted me and even, on occasion, given joy … The dog, the suicide, the writing life: These are the three strands of thought and feeling that make up the weave of The Friend. They don’t always mesh or make a satisfying design, but they are held together by the tone of the narrator’s voice: light, musing, curious, and somehow wonderfully sturdy … The heartbreak inscribed in those final words fills the page to the margin and beyond with the penetrating loneliness—the sheer textured burden of life itself—that all of Sigrid Nunez’s fine writing had been at brilliant pains to keep both within sight and at bay … From beginning to end, I thought myself engaged.”

–Vivian Gornick, Bookforum

2017

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

(Scribner)

Sorrow is food swallowed too quickly, caught in the throat, making it nearly impossible to breathe.

“Ward’s characters are much more than their scars. The novel suggests that you have resources to get you through, regardless of your circumstances. Some of those resources are not tallied by experts. The ear might be a better way of finding those resources than looking at numbers on a spreadsheet. And it takes a certain kind of ear … She [Ward] accepts—perhaps welcomes—her characters, with all their flaws … Sing, Unburied, Sing honors paying attention: seeing, listening, and, finally, singing. The novel inspires me to think that we need new songs, new ways of seeing, new ways of listening.”

–Anna Deavere Smith, The New York Review of Books

2016

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

(Doubleday)

Stolen bodies working stolen land. It was an engine that did not stop, its hungry boiler fed with blood.

“…a potent, almost hallucinatory novel that leaves the reader with a devastating understanding of the terrible human costs of slavery. It possesses the chilling matter-of-fact power of the slave narratives collected by the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s, with echoes of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and brush strokes borrowed from Jorge Luis Borges, Franz Kafka and Jonathan Swift … [Whitehead] has told a story essential to our understanding of the American past and the American present.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

2015

Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson

(Random House)

The truth is, though, that you don’t need to die to know what it’s like to be a ghost.

“As with The Orphan Master’s Son, there’s a great deal of comedy to be found in Fortune Smiles, though the humor in this new book is offset by a darkness so pervasive I found it seeping into my daily life. Despairing men are at the heart of each of these tales, most of them protagonists on the cusp of being antagonists … Each of these stories plants a small bomb in the reader’s head; life after reading Fortune Smilesis a series of small explosions in which the reader—perhaps unwillingly—recognizes Adam Johnson’s gleefully bleak world in her own … the stories in Fortune Smiles may be best appreciated when taken out into the sunshine one by one.”

–Lauren Groff, The New York Times Book Review

2014

Redeployment by Phil Klay

(Penguin Press)

She spent all his combat pay before he got back, and she was five months pregnant, which, for a Marine coming back from a seven-month deployment, is not pregnant enough.

“Klay succeeds brilliantly, capturing on an intimate scale the ways in which the war in Iraq evoked a unique array of emotion, predicament and heartbreak. In Klay’s hands, Iraq comes across not merely as a theater of war but as a laboratory for the human condition in extremis … Each story calls forth a different dilemma or difficult moment, nearly all of them rendered with an exactitude that conveys precisely the push-me pull-you feelings the war evoked: pride, pity, elation and disgust, often pulsing through the same character simultaneously … Klay has a nearly perfect ear for the language of the grunts—the cursing, the cadence, the mixing of humor and hopelessness. They are among the best passages in the book, which, unfortunately, are unfit for a family newspaper.”

–Dexter Filkins, The New York Times Sunday Book Review

2013

The Good Lord Bird by James McBride

(Riverhead)

The Good Lord Bird don’t run in a flock. He Flies alone. You know why?

He’s searching. Looking for the right tree.

“… a boisterous, highly entertaining, altogether original novel … Mistake follows mistake in this rambunctious comedy of errors, and Old Man Brown and his hard-riding horde head straight to the Kansas flatlands to rescue 11-year-old Henrietta from slavery … There is something deeply humane in this, something akin to the work of Homer or Mark Twain. We tend to forget that history is all too often made by fallible beings who make mistakes, calculate badly, love blindly and want too much. We forget, too, that real life presents utterly human heroes with far more contingency than history books can offer.”

–Marie Arana, The Washington Post

2012

The Round House by Louise Erdrich

(Harper)

Now that I knew fear, I also knew it was not permanent. As powerful as it was, its grip on me would loosen.

It would pass.

“Erdrich’s plotting is masterfully paced: the novel, particularly the second half, brims with so many action-packed scenes that the pages fly by. And yet the author also knows just when to slow down, reminding us that despite everything upending Joe’s life, he’s still just a teenager … One of the most pleasurable aspects of Erdrich’s writing is that while her narratives are loose and sprawling, the language is always tight and poetically compressed … There’s nothing, not the arresting plot or the shocking ending of The Round House, that resonates as much as the characters. It’s impossible to stop thinking about the devastating impact the desire for revenge can have on a young boy.”

–Molly Antopol, The San Francisco Chronicle

2011

Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward

(Bloomsbury)

I will not let him see until none of us have any choices about what can be seen, what can be avoided, what is blind, and what will turn us to stone.

“Jesmyn Ward makes beautiful music, plays deftly with her reader’s expectations: where we expect violence, she gives us sweetness. When we brace for beauty, she gives us blood … Best of all, she gives us a singular heroine who breaks the mold of the typical teenage female protagonist. Esch isn’t plucky or tomboyish. She’s squat, sulky and sexual. But she is beloved—her brothers Randall, Skeetah and Junior are fine and strong; they brawl and sacrifice and steal for her and each other. And Esch is in bloom … For all its fantastical underpinnings, Salvage the Bones is never wrong when it comes to suffering. Sorrow and pain aren’t presented as especially ennobling. They exist to be endured—until the next Katrina arrives to ‘cut us to the bone.’”

–Parul Sehgal, The New York Times Sunday Book Review

2010

Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon

(McPherson & Co.)

I was an easy birth, and I have never regretted it. Not even for a visit would I return to the womb.

“Void and menace are the operating principles in Lord of Misrule. First, it’s hard to sort the men from the horses, so similar are their slaveries, their striving for nothing, their tendency to be ruled by lesser animals … This rich, soupy (as in primal soup, many ingredients) milieu that Gordon creates—all the names and hints of back story glimmering in the dust—serve to make a character shine, really shine, when he or she rises up and out. You hear chains popping all through this novel, little acts of will and big acts of self-determination. It’s astonishing how quickly, with all this description, Gordon can get to a philosophical point or make a character unforgettable.”

–Susan Salter Reynolds, Los Angeles Times

2009

Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann

(Random House)

The thing about love is that we come alive in bodies not our own.

“Through a Joycean tangle of voices—including that of a fictionalized Petit—he weaves a portrait of a city and a moment, dizzyingly satisfying to read and difficult to put down … Like Joyce’s Ulysses—also a portrait of a city and a day—the chapters’ formats and prose styles vary widely … Not everyone here is admirable, but all are depicted with sympathy and care. Each leaves its own color on the book’s canvas and then departs; no narrator is repeated except the tightrope walker, the conductor who has brought this orchestra together.”

–Moira Macdonald, The Seattle Times

2008

Shadow Country by Peter Matthiessen

(Modern Library)

This world is painted on a wild dark metal.

“…a novel of Faulknerian power and darkness, one that embraces the American experience from the time of the Civil War to the first years of the Depression … While Shadow Country gradually conveys what is known about Watson from records and reminiscences, Matthiessen imagines conversations and the background for certain characters and encounters, even as he deepens the ambiguities of his increasingly tantalizing story … While Book I draws on the down-home voices of the islanders and Book II uses the prose of a good reporter, Book III is written in a rather formal, old-fashioned style, suitable for the scion of proud, if now indigent, Southern aristocrats … Shadow Country is altogether gripping, shocking, and brilliantly told, not just a tour de force in its stylistic range, but a great American novel, as powerful a reading experience as nearly any in our literature.”

–Michael Dirda, The New York Review of Books

2007

Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson

(FSG)

She had nothing in this world but her two hands and her crazy love for Jesus, who seemed, for his part, never to have heard of her.

“It’s a powerful story about the American experience in Vietnam, with unsettling echoes of the current American experience in Iraq … Skip believes in the goodness and promise of America with boyish innocence and ardor…Skip’s innocence, however, is tarnished when he witnesses the agency’s brutal assassination of a priest (falsely suspected of running guns) in the Philippines, and in Vietnam he quickly becomes lost in the wilderness of mirrors created by his fellow intelligence officers … Mr. Johnson intercuts the stories of Skip and the colonel with those of half a dozen other people caught up in the war … Mr. Johnson not only succeeds in conjuring the anomalous, hallucinatory aura of the Vietnam War as authoritatively as Stephen Wright or Francis Ford Coppola, but he also shows its fallout on his characters with harrowing emotional precision.”

–Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

2006

The Echo Maker by Richard Powers

(FSG)

Nothing anyone can do for anyone, except to recall: We are every second being born.

“The Echo Maker is not an elegy for How We Used to Live or a salute to Coming to Grips, but a quiet exploration of how we survive, day to day … The faith we extend to writers like Weber is, I think, the same kind of faith we put in our best fiction writers. We expect—and need—them to tell us of our world, how things work, how against all odds we make it through. With The Echo Maker, Richard Powers vindicates this faith, employing his trademark facility with all manner of esoteric discourse, but never letting it overcome the essential human truth of his characters … I haven’t mentioned the expert plot mechanics yet, Powers’s array of tiny enigmas and red herrings, all perfectly paced … As the features of life after 9/11 come into focus, Powers accomplishes something magnificent, no facile conflation of personal catastrophe with national calamity, but a lovely essay on perseverance in all its forms.”

–Colson Whitehead, The New York Times Book Review

2005

Europe Central by William T. Vollmann

(Viking)

Maybe life is a process of trading hopes for memories.

“Vollmann’s [novel] is a hall of mirrors—each tale getting a kind of sister story that forms its opposite image. Enter the book, take a twirl around, and you are presented with a kind of kaleidoscopic portrait of life in Europe around the dawn of World War II, when totalitarianism was on the rise. Try to find your way out and you will become, well, a little lost. This sense of claustrophobia and confusion is, one imagines, purposeful, as Europe Central aims to show how totalitarianism occurred and how it felt on the inside, and to bring us up close and personal with the nubbly texture of history.”

–John Freeman, The Boston Globe

2004

The News From Paraguay by Lily Tuck

(Harper Perennial)

Surprising yourself is a big thing for me—to go somewhere that I don’t even know I’m going.

“The historical novel The News From Paraguay finds its epic story in an important political crossroads for Paraguay … Like a slowly opening fan whose slats reveal themselves one by one, so do the many stories within The News From Paraguay. Tuck’s omniscient narrator finds an interesting tale in just about every character and encounter. Each brief self-contained diversion—whether of Ella’s maid having her broken arm amputated or a doctor’s fatal spill after urinating in a lake—crystallizes the whole in miniature.”

–Linda Burnett, The San Francisco Chronicle

2003

The Great Fire by Shirley Hazzard

(FSG)

My need of your words: for such closeness there should be a word beyond love.

” …a classic romance so cleverly embedded in a work of clear-eyed postwar sagacity that readers will not realize until halfway through that they are rooting for a pair of ill-starred lovers who might have stepped off a Renaissance stage … This is not a novel of war and its aftermath so much as a study of how people act, and how they are acted upon, in the wake of violent disruption. After you shake the chessboard, how will the pieces realign themselves? … The greatest pleasure is her subtle and unexpected prose…Never lyrical for the sake of lyricism, [it] follows the sensible course of her characters—open to beauty and alert to its dangers.”

–Regina Marler, Los Angeles Times

2002

Three Junes by Julia Glass

(Pantheon)

I, too, seem to be a connoisseur of rain, but it does not fill me with joy; it allows me to steep myself in a solitude I nurse like a vice I’ve refused to vanquish.

“Julia Glass has written a radiant first novel that turns the story of Scotland native Fenno McLeod and his real and extended family of ‘upper-crusty Ivanhoe’ types, creative women and urban gay men into an intimate literary triptych of lives pulled together and torn apart … Paul’s story is a finely detailed portrait of a somewhat ordinary life and the handful of people, past and present, who make their way into it. But the novel’s most sustained scrutiny is reserved for Fenno, Paul’s bibliophile eldest son who has a preference for men and remains devoted to the mother whose passionate life, tragically cut short by lung cancer, he never really understood. Fenno’s lengthy first-person narrative takes its place at the literal and symbolic center of Three Junes, providing the anchor point for the intricate web of characters that make up Glass’ thoughtful textual design.”

–Laura Ciolkowski, The Chicago Tribune

2001

The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen

(Picador)

Elective ignorance was a great survival skill, perhaps the greatest.

“Franzen shores up his Zeitgeist-heavy narrative with the indispensable masonry of a carefully crafted plot, exuberant yet plausible satire and, most of all, closely observed character … Franzen narrates The Corrections with a subdued, assured and compassionate touch. The result is an energetic, brooding, open-hearted and funny novel that addresses refreshingly big questions of love and loyalty in America’s rapidly fragmenting, meaning-challenged domestic sphere … What happens to the Lamberts is ultimately less compelling than the simple fact of them, as rendered in Franzen’s patient, wise descriptions of their petty trials, their epic self-deceptions and their astonishing, resilient need of one another.”

–Chris Lehmann, The Washington Post

2000

In America by Susan Sontag

(Picador)

Each of us carries a room within ourselves, waiting to be furnished and peopled, and if you listen closely, you may need to silence everything in your own room, you can hear the sounds of that other room inside your head.

“In America is a picaresque fable, a historical tragicomedy. The story revolves around a Polish actress, Maryna Zalezowska. More than an actress, she is a national symbol for the triply besieged and conquered Poland, a symbol of patriotism, of seriousness, of achievement on a grand scale in the arts … [Sontag] is giving us, in fiction, the history of the loss that led to irony and fragmentation, the death of so much that could formerly be called culture, and she bravely attempts a journey beyond that loss. Sontag has managed to structure a paradox—call it hopeful inconsolability or optimistic pessimism—a belief that the destruction of our ideals and our long-lost innocence can still be narrated, that there is still a story to be told about us and about how we came to be the way we are or to see.”

–Michael Silverblatt, Los Angeles Times

NONFICTION

2020

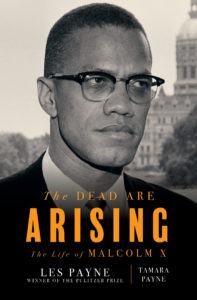

The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X by Les Payne and Tamara Payne

(Liveright)

“…this kind of textured attention to Black life and community, whether in Omaha or Boston, Atlanta or Accra, distinguishes Les Payne’s masterful biography, The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X … a meticulously researched, compassionately rendered, and fiercely analytical examination of the radical revolutionary as a human being … a portrait that pushes us beyond the adolescent hero worship that many in my generation cling to in our current political moment as we reread Malcolm X, C. L. R. James, Angela Davis, and other Black thinkers … With new information gleaned from decades of research, Payne sheds fresh light on key moments in Malcolm’s political journey … Because Payne takes the memories and views of Black communities seriously—because he never assumes that Malcolm’s Black contemporaries experienced him in the same way that we describe him in the present—The Dead Are Arising provides an invaluable glimpse into the mechanics of community mobilization led by Black women … The Dead Are Arising forces us to ask deeper, more complicated questions about the Black people and places from which our heroes come.”

–Kerri Greenidge (The Atlantic)

2019

The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom

(Grove Press)

“…[an] extraordinary, engrossing debut … Broom…pushes past the baseline expectations of memoir as a genre to create an entertaining and inventive amalgamation of literary forms. Part oral history, part urban history, part celebration of a bygone way of life, The Yellow House is a full indictment of the greed, discrimination, indifference and poor city planning that led her family’s home to be wiped off the map. It is an instantly essential text, examining the past, present and possible future of the city of New Orleans, and of America writ large … Broom is our guide, but not the sort who holds readers’ hands, uninterested as she is in tidy transitions between one type of writing and another. The through line is her thought process, her frequent questioning … The interviews also yield unforgettable scenes … The true test of her worthiness is her empathy and focused attention. She is a responsible historian, granting her subjects the grace of multiple examinations over the years … Broom’s deadpan humor comes through clearest in her descriptions of herself … The Yellow House is a book that triumphs much as a jazz parade does: by coming loose when necessary, its parts sashaying independently down the street, but righting itself just in the nick of time, and teaching you a new way of enjoying it in the process.”

–Angela Flournoy, The New York Times Book Review

2018

The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke by Jeffrey C. Stewart

(Oxford University Press)

“…a vitally important, astonishingly well researched, exhaustive biography of the brilliant, complex, flawed, utterly fascinating man who, if he did not start the movement, served as its curator, intellectual champion, and guiding spirit … His account of Locke’s life is detailed, sometimes astoundingly so, but never descends into tedium. More important, he displays a thorough grasp of the intellectual challenges Locke took on … On his death, in 1954, Locke left behind achievements that deserve to be more widely celebrated, and this biography represents a serious, worthy attempt to get the party started.”

–Clifford Thompson, The Wall Street Journal

2017

The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia by Masha Gessen

(Riverhead)

“…a magisterial, panoramic overview of Russia under Putin … While the people she singles out are often vociferous opponents of the rearward direction of the New Russia, she gives at least equal time to the group the perestroika historian Yuri Afanasyev dubbed ‘the aggressively obedient majority’ and to the tens of millions of ordinary Russians who would be happy to go back to the USSR, more or less … The characters’ personal histories add life and nuance to Gessen’s narrative. But it takes a while to get a handle on all of the players, who are as numerous as the cast of a Tolstoy novel, if less romantically clad. But portraying the politics of totalitarianism does not call for a romantic filter. Gessen’s reconstruction of the ongoing saga of Russia’s reversion to vozhdizm makes for thrilling and necessary reading for those who seek to understand the path to suppression of individual freedoms, and who recognize that this path can be imposed on any nation that lacks the vigilance to avert it.”

–Liesl Schillinger, The Barnes and Noble Review

2016

Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi

(Bold Type Books)

“… a lucid, accessible survey of how ‘the people’ were racialised over 500 years … Kendi confidently re-evaluates the writings of many celebrated abolitionists and African-American heroes and concludes that racism often underpinned their strategies … Kendi’s most important insight might help rethink anti-racist activism … One might expect Kendi to be despondent, but he believes that eradicating discriminatory policies will consign racist ideas to the past … an un-yielding narrative of racist ideas, violence and harm. However, the book is also a history of refusals.”

–Sadiah Quereshi, The New Statesman

2015

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

(Spiegel & Grau)

“The book is polemical at times, but it’s also driven by probing reporting and a loving intimacy. For example, Coates writes with tremendous power, but also intense grief, about a dashing African-American college friend who was shot by a police officer under highly suspicious circumstances outside Washington, D.C., more than a decade ago … demonstrates this author’s admirable ability to interrogate himself and challenge his own attitudes and ideas, while picking apart those generally held by the society he lives in. Coates’ book possesses a brooding eloquence that only carefully channeled anger and sadness can produce … stands to become a classic on the subject of race in America.”

–Tyrone Beason, The Seattle Times

2014

Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, & Faith in the New China by Evan Osnos

(FSG)

“Age of Ambitionis…a riveting and troubling portrait of a people in a state of extreme anxiety about their identity, values and future … eclectic portraits are drawn from across the political spectrum … Some of these characters appear several times, giving the book a cumulative impact that helps persuade the reader that China has lost its way. The remarkable story of Lin Yifu, the Taiwanese defector who swam across the strait to become the World Bank’s chief economist and later a cheerleader for China’s economic prosperity, provides a strong narrative thread. So, too, does the story of the persecuted artist Ai Weiwei … Mr. Osnos has a keen grasp of how the Internet has transformed China’s political landscape, circumventing the government’s efforts to manage information about public incidents.”

–Judith Shapiro (The New York Times)

2013

The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America by George Packer

(FSG)

“… ambitious … a fascinating hybrid … Packer, an economical and often elegant writer, interweaves these stories, told in short takes, with reporting on distinctive American locales … a richly complex narrative brew … Don’t read The Unwinding expecting either grand epiphanies or nuts-and-bolts solutions to America’s problems—only graceful writing and modest faith that a few dreamers and strivers among us may lead the way to a better future.”

–Julia M. Klein (The Chicago Tribune)

2012

Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity by Katherine Boo

(Random House)

“…the butterfly effect of the harrowingly interrelated global economy described in Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Katherine Boo’s first book, Behind the Beautiful Forevers…narrative nonfiction work catalogs a period of three years, beginning before the global market crash of 2008, of the Husain family, supported by a teenage trash-buyer named Abdul, and others who scrape together a living in a slum called Annawadi…depicts a modern India in the throes of embracing the Western-spun dream of unchecked capitalism and the upward mobility that supposedly comes with it… The great irony exposed within the book’s finely wrought pages, however, is the lie of equality in the new age of global markets, particularly when it comes to the extremely poor …a richly detailed tapestry of tragedy and triumph told by a seemingly omniscient narrator with an attention to detail that reads like fiction while in possession of the urgent humanity of nonfiction.”

–Jessica Gelt, Los Angeles Times

2011

The Swerve: How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt

(W.W. Norton)

“The Swerveis one of those brilliant works of non-fiction that’s so jam-packed with ideas and stories it literally boggles the mind. But throughout this profusion of riches, it seems to me, a moral emerges: something about the fragility of cultural inheritance and how it needs to be consciously safeguarded. Greenblatt, of course, doesn’t preach, but, instead, as a master storyteller, he transports his readers deep into the ancient and late medieval past; he makes us shiver at his recreation of that crucial moment in a German monastery when modern civilization, as we’ve come to know it, depended on a swerve of the Poggio’s grasping fingers.”

–Maureen Corrigan, NPR

2010

Just Kids by Patti Smith

(Ecco Press)

“At one level, the book’s interest is a given … The surprise is that it’s never cryptic or scattershot … Just Kidsis the most spellbinding and diverting portrait of funky-but-chic New York in the late ’60s and early ’70s that any alumnus has committed to print. The tone is at once flinty and hilarious, which figures: [Smith’s] always been both tough and funny, two real saving graces in an artist this prone to excess. What’s sure to make her account a cornucopia for cultural historians, however, is that the atmosphere, personalities and mores of the time are so astutely observed. No nostalgist about her formative years, Smith makes us feel the pinched prospects that led her to ditch New Jersey for a vagabond life in Manhattan … Most often, you’re simply struck by her intelligence, whether she’s figuring out why an acting career doesn’t interest her… or sizing up the ultra-New York interplay between the city’s fringe art scenes and the high-society sponsorship to which Mapplethorpe was drawn … This enchanting book is a reminder that not all youthful vainglory is silly; sometimes it’s preparation.”

–Tom Carson, The New York Times Book Review

2009

The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt by T.J. Stiles

(Knopf)

“Stiles demonstrates a brute eloquence of his own. This is a mighty—and mighty confident—work, one that moves with force and conviction and imperious wit through Vanderbilt’s noisy life and time … full of sharp, unexpected turns … The most flat-out enjoyable sections are those that deal with New York’s great steamship wars of the first half of the 19th century … Mr. Stiles is clear-eyed about his subject’s nearly amoral rapacity … Mr. Stiles gets Vanderbilt the man onto paper. He is eloquent on Vanderbilt’s love of horses and horse racing, his tangled relationships with his 13 children and his dabbling in the occult … There are moments in any biography of this size when your eyes are going to glaze over; I certainly did not wish The First Tycoon were longer. But I read eagerly and avidly. This is state-of-the-art biography, crisper and more piquant than a 600-page book has any right to be.”

–Dwight Garner, The New York Times

2008

The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon-Reed

(W. W. Norton)

“The Hemingses of Monticello is a brilliant book. It marks the author as one of the most astute, insightful, and forthright historians of this generation. Not least of Annette Gordon-Reed’s achievements is her ability to bring fresh perspectives to the life of a man whose personality and character have been scrutinized, explained, and justified by a host of historians and biographers … While praising her grasp of the sources, her legal acuity, her erudition, and the stylishness of her narrative, it remains to be said that her great achievement lies in telling this story. Because it is one of the stories that really matter.”

–Edmund S. Morgan and Marie Morgan, The New York Review of Books

2007

Legacy of Ashes: The HIstory of the CIA by Tim Weiner

(Doubleday)

“Weiner deftly and succinctly shows how the agency has navigated the first sixty years of its existence … Among the more shocking revelations of the book are the many urban legends that are, in fact, true … Weiner masterfully exposes the incompetence of the agency and the men who’ve led it. Using a relentless narrative style that dispenses with lengthy biographies of even the most important individuals, he pushes through a staggering amount of raw information in relatively short order. His prose is sharp, and never condescends to the reader … For all its weight, the book has surprising moments of humor … One can’t help but share Weiner’s frustration about the CIA’s past, as well as his fear for what its failures mean for America’s future. Legacy of Ashes is the rare book that should be read by every American, especially in an election year. Luckily, it’s also a thoroughly enjoyable book, one that’s hardly a chore to read.”

–Patrick Brown, The Millions

2006

The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl by Timothy Egan

(Houghton Mifflin)

“Illuminating these hidden lives serves to strengthen the larger story of the Dust Bowl. Egan nimbly moves his lens between macro and micro, balancing hard data and national conditions with portraits of people you come to care about … Occasionally Egan’s writing edges toward the theatrical, but more often than not his style swells to fit the magnitude of monster storms and scales down to the individual families trapped in mind-numbing poverty … Egan has gone beyond statistics to reach the heart of this tragedy. The Worst Hard Timeprovides a sobering, gripping account of a disaster whose wounds are still not fully healed today.”

–Carol Iaciofano, The Boston Globe

2005

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

(Vintage Books)

“A writer all her life (Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Democracy, A Book of Common Prayer among others), few are more expert than Didion at cleanly parsing thoughts and feelings … What she has produced, with remarkable clarity, is a record of her thoughts and feelings during her first year of bereavement … If Didion’s narrative sounds heartrending, it is—utterly so. But at the same time, it is a work of much majesty … But The Year of Magical Thinking is also something more…it is particularly touching to read about a decades-long partnership that thrived … We her readers are left simply to admire both her bravery and her skill, and to offer whatever intelligent compassion we can from afar.”

–Marjorie Kehe, The Christian Science Monitor

2004

Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Right, and Murder in the Jazz Age by Kevin Boyle

(Henry Holt)

“Kevin Boyle’s Arc of Justice is by far the most cogent and thorough account yet of the trial and its aftermath … One of its virtues is the way Boyle vividly recreates the energy and menace of Detroit in 1925 … Boyle deftly shows how the trial took on different meanings for its various players … Those working-class whites are the only people who remain more or less faceless in Boyle’s narrative. He does explain how their fear of black interlopers was rooted in the city’s precarious economics: mortgages were so hard to finance that a drop in property values could mean eviction for many families.”

–Robert F. Worth, The New York Times Book Review

2003

Waiting for Snow in Havana: Confessions of a Cuban Boy by Carlos Eire

(Free Press)

“… succeeds … [Eire] has done a splendid job. The memoir is masterfully written, bursting with wonderful details and images and populated by characters so well described that they seem to be sitting next to you on the couch … Eire has a leisurely, conversational way of telling his story … The book has its flaws, but once you’ve fallen under the spell of the author’s charming, sympathetic, sorrowful voice, they all seem minor … without that love, both for his family and for the country he left behind, it seems unlikely that Eire could have written such an extraordinary book.”

–Curtis Sittenfeld, The Washington Post

2002

The Years of Lyndon Johnson: Master of the Senate by Robert A. Caro

(Knopf)

“…it is Caro’s great achievement that in more than 1,000 pages contained in this volume he has massively extended his work on Lyndon Johnson without in any way diluting its quality … To me this book stands out because it brings that pace and drama to life: it makes it almost as exciting to read the book as it would have been to be there … Caro’s achievement…is not only vividly to tell the story of one remarkable man. It is also to explain with clarity the lives of the people he worked with, the history of the institutions in which he exercised his power, and the deep social forces which moved those people and institutions to action. When a fourth volume finally completes the set, this will be nothing short of a magnificent history of 20th-century America.”

–William Hague, The Telegraph

2001

The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression by Andrew Solomon

(Scribner)

“… exhaustively researched, provocative and often deeply moving … Readers should not be discouraged by the opening chapter, titled Depression, which is the least coherent chapter in the book, lurching from point to point as if awaiting a principle of inspired organization that never arrives … Even when writing more or less straightforward journalism, Solomon writes engagingly; his style is intimate and anecdotal, and often bemused … Amid so much information, the author might have been more discriminating and skeptical … a considerable accomplishment. It is likely to provoke discussion and controversy, and its generous assortment of voices, from the pathological to the philosophical, makes for rich, variegated reading. Solomon leaves us with the enigmatic statement that ‘depression seems to be a peculiar assortment of conditions for which there are no evident boundaries’—exactly like life.”

–Joyce Carol Oates, The New York Times

2000

In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex by Nathaniel Philbrick

(Penguin)

“…a mix of holy seawater, hot blood and searching analysis. Philbrick has elevated the adventure of the Essex to a rich and disturbing study of the secret root-tangles of how and why things happened as they did, holding up what we know now of human and animal behavior against the 1820 circumstances and actions … The approach is unusual and fresh, the book intelligent, probing, scholarly, gripping and satisfying. It sets a new mark for maritime literature, away from the traditional adventure pattern. And for all his erudite knowledge applied to the complexities of human behaviours, Philbrick does not neglect to note the random twists of fate that make or ruin a life … Much of the literary excellence of In the Heart lies in its fine and introspective passages … The Nantucket of 1820 in Philbrick’s pages comes across as a strange and somewhat sinister place, characterised by familiarity with death, clannishness, class divisions, stored anger, sharp business practices, and oppression.”

–Annie Proulx, The Irish Times