“Let That Dream Die.“ On Watching Tennis and (Actually) Becoming the Best Writer You Can Be

Veronica Roth’s Argument for Embracing the Unknown

In 2020, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal—two of the “Big 3” of men’s tennis who have dominated the rankings since 2006—didn’t enter the US Open because of the pandemic, and the third member of the Big 3, Novak Djokovic, hit a ball behind him in a moment of careless frustration and struck a line judge in the throat.

The line judge recovered, Djokovic was defaulted, and suddenly, none of the tennis titans who had long stood between the younger generation and victory were there anymore. For the first time since 2016, we would have a new grand slam champion, and the energy was frantic. All the players were practically vibrating out of their shoes. I tuned into more matches than not, sucked in by the drama, and since then I’ve been an enthusiast.

Watching tennis makes my mind go silent. This is, I imagine, what happens to other people when they’re engaged in a hobby they enjoy—but the only hobby I had ever taught myself to enjoy was writing, and when it became my job, I had nothing to fill the vacancy. Now I have tennis, and specifically, I have Daniil Medvedev.

Medvedev is my favorite player, hands down. His game is, to put it lightly, weird. He’s 6’6” and gangly. When he hits a forehand, his racquet ends up wrapped around his neck. When he hits a backhand, he sometimes folds in on himself, legs crossed, like one of those donkey toys that collapses when you push the button underneath it. The others on tour refer to him as “the octopus” or “the spider.” Twitter refers to him as “Squidward.” I refer to him as “Wacky Waving Inflatable Arm Flailing Tube Man.”

He moves with speed that doesn’t make sense, hits angles that shouldn’t be possible, and hits a first serve down the T that’s basically unreturnable. When he’s on his game, Medvedev is an unstoppable force, and despite his on-court volatility, his occasional emotional meltdowns, and his borderline villain status (depending on the tournament), I watch every one of his matches that I can.

After he won the 2021 US Open, I read an old interview with his coach, Gilles Cervara, in which he said this:

When we worked together, we were both unsure if he could get to this level. He’s not saying, “I want to win this tournament and be at this level.” He’s saying, “I want to be the best I can be,” whether it’s in the next practice session or on the next point. These are the small details that bring results.

This strikes me as not the typical narrative for a prodigy athlete. Usually for people at the very top of athletic achievement, I hear stories of their natural talent, their indefatigable will to succeed, and the certainty of their success even from the beginning. I don’t hear that neither coach nor athlete are sure that they’re good enough to make it to the very top, but they’ll work hard and see what comes of it.

With each new book I exhort myself, as I now exhort you, to let that dream die over and over again, and instead focus on finding the best story you can at any given moment.And I do pay attention to remarkable stories of young success, because how can I not? At age 22, I lived one. I wrote Divergent, which was a runaway hit, complete with bestseller-list status, record-breaking sales, and a movie adaptation; pretty much the full list of writer dreams come true. In the aftermath of that series, I was left with wonderful memories and immense gratitude and also a big empty space where my goals used to be.

In interviews about his 2021 US Open victory against Djokovic, Medvedev’s answers were revealing. “Did you do anything special to prepare for this match?” No. “Does this win change anything for you?” No. This is a different kind of void. No goals beyond the commitment to work hard in this moment, and then the next one. To see where that work leads you instead of driving yourself toward it.

If I could articulate how I’ve approached moving forward after the wonderful and strange events that characterized my early career, it would be this: I have not replaced my old dreams with new ones. I have not rushed to fill that void. Instead I live in each book, committed to doing the daily, often tedious work of improvement. And as helpful as this has been to me on the macro level, it has been even more helpful on the micro level, as I tackle each new book with the intention to make it noticeably better than the last.

A book starts small: with a character, a plot, a concept. And unavoidably, as I work my way through my rough draft, I approach it with an idea of what it’ll become, of what it’s about, of what it means. The problem with this is that writing is both a conscious and an unconscious process. I control the words I’m putting on the page, and my intention shapes every draft I write in obvious ways. But there are always pieces of me that leak out whether I want them to or not: beliefs I hold that I am not consciously considering, memories I draw from that are buried too deep to articulate, a flow of logic that only after seeing the whole of the story can I begin to comprehend.

The book is new for me, but it’s also familiar, the result of growing in my writing while remaining the writer that I am—the result of embracing the void.Often, when I get stalled when revising, it’s because I am clinging to my original vision for a story without looking at what’s in front of me. I am too in love with the ray of inspiration that pierced me at the start and not interested in taking a sincere look at what I have in my hands, a draft that has taken its own shape thanks to the unconscious as well as the conscious processes of my writing.

I see this happening with less-experienced writers who come into my Instagram DMs with craft questions, as well as with more-experienced writers as we talk through their editorial letters and critiques. Some writers set out to write an inversion of a hero journey and end up writing a sincere fulfillment of it. We set out to write about a character turning into a villain and end up writing about trauma. We set out to write a serious literary novel and end up with a fizzy commercial one. We can either embrace what we have, stripping away the aspects of the story that are now no longer necessary, or we can resist and end up with six of one thing and a half-dozen of the other.

I call letting go of these original conceptions of our work “embracing the void” because that’s how it feels: like that weightless moment when you think there’s another step beneath you, but you’ve already reached the landing. Like you’re throwing away all that you’ve worked toward in favor of something you aren’t even sure you can execute. In those moments, you have to trust in the work you’ve done to become the writer you are, and you have to believe that the new version of your story could be better than the one you initially devised. You have to let go of the thing you love and embrace the thing you don’t know. You do it because it results in something stronger and more cohesive, and because the things we love, as writers, are often the things we most need to let go of.

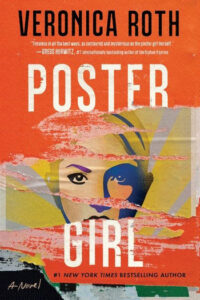

My most recent book, Poster Girl, is about a collapsed authoritarian regime and a former propaganda “poster girl” sorting through its wreckage. While I was drafting Poster Girl, I thought I was writing something quiet and meditative, unlike anything I had written before. A bit of a risk for a writer like me, who has thus far lived squarely in action-packed genre novels.

What I discovered through the writing is that although the thoughtfulness of my initial conception is still present in the book, and indeed one of its central concerns, I require a scaffold to build my stories and characters. I had to let go of this idea of doing something completely new and accept the plot and world-building that were fighting to emerge inside of it.

My “poster girl,” Sonya, now sorts through the wreckage of that collapsed regime while she searches for a missing child, a seemingly impossible task that takes her to dark and dangerous places. The scaffold is a mystery novel that veers into thriller, a structure that provided me the freedom to explore the character in the way that I needed to. The book is new for me, but it’s also familiar, the result of growing in my writing while remaining the writer that I am—the result of embracing the void.

A dream of a book is not a book. With each new book I exhort myself, as I now exhort you, to let that dream die over and over again, and instead focus on finding the best story you can at any given moment. In other words, no matter what obstacles confront you, your goal is always the same: find a way to get the ball over the net.

__________________________________

Poster Girl by Veronica Roth is available via William Morrow & Company.