Lessons on Community From a Father Reading Dostoyevsky

Chris Dombrowski on Service and Care in Missoula, Montana

Several pounds of peeled potatoes boil in a ten-gallon steel pot. Covering kitchen duty at the homeless shelter where I’m employed part-time, I take another potato from a burlap sack and begin to peel. My cooking partner, a drifter named Carl who’s made his way to Missoula from Wyoming and speaks in the staccato cadence I’ve come to associate with the displaced, stirs the pot with a wooden spoon. His dizzy spin downward, he informs me, began with a harmless bar fight. Carl’s hands look heavy and his face, under a mantle of stubble, bears a grin of staunch recalcitrance.

After that night at the Mint, he says, he posted up for a few weeks in Cheyenne. “I tossed this skinny rig-driller around. Broke a table and a few pool cues is all,” he says, brushing a stubborn yellow shaving from his forehead. “Went back to pay down the damage but I was short a hundred. Owner said he’d let me work it off as a bouncer, while I was in arrears, is what he said. One night Chris LeDoux walks in. The country music star. Chris LeDoux. Had a big million-dollar spread in the valley. Some cowhand gets shit talkin’ his music, whole thing dusts up. I yank LeDoux outta the fray and flatten the cowhand. Next day he offers me a job working security at his shows.”

“Who does?” I ask.

“LeDoux. But my ex erased his number from my phone. She was pissed her cousin sent me a dirty text, and went through my whole contacts just deleting. Otherwise I’d be there running personal security, boy. High-hogging it. Vegas Strip.”

After dinner prep, as the residents and guests shuffle red-cheeked through the supper line, Carl and I sweep the floors along with Sonja, a frequent visitor to the shelter whose weathered way of appearing simultaneously eighteen and forty-eight years old always disarms me. By way of a greeting, she offers that she was just released from County for stealing video equipment from one of the big box stores out on Reserve Street.

“First offense,” she continues, stripping the hairnet off her head and rubbing at the indentation left by the net’s elastic band. “First time they caught me anyway. Reason they released me out after just four days is ’cause I’m breast-feeding. I’ve been walking out of there with garbage cans full of stuff for months. I just borrow my girlfriend’s fur coat and walk in that store like a rich woman. Plop a hundred-gallon Hefty can in my cart and fill it with anything I can sell. CDs, VCRs, nightgowns. Go to the back of the store and put the lid on tight, pay for the can with a twenty. Feed my kids off the haul till the first.”

The only way to make sense of the suffering of others is to assume responsibility for them, my dad once said, quoting, I’d later learn, Dostoyevsky.“How you gonna feed kids off shit you stole?” asks Carl, shaking his head and handing me a stack of wet food trays from the dish line. “These people. Wish I had some bus fare. Or a goddamn horse. I’d ride tonight.”

I fit an aluminum tray onto the stack, pondering to what end I would go to provide for a child, and whether all children weren’t, in some small way, my own. Despite the fact that many people in the world feed their children off crimes of one ilk or another—blue collar, white collar—there’s a warped mythology in the West that imagines each individual striking out level on the same green pasture and eventually hitting pay dirt. In reality, like everywhere else in the world, the cards are stacked against the less fortunate.

“These people,” Sonja says, pursing her lips. “You wish in one hand, cowboy, pick turds with the other. See which fills up first.”

“I’ll show you my hand right now—you want to see it?” Carl says.

“Hey” I say, trying to stop the chippiness from escalating, for their sakes especially. “You know if staff has to come in here and break this up you’ll both be out of a bunk tonight. Let me cover your dish duty, Carl. How about you hop in line?”

Carl yanks silverware from the receptacles, grumbling something about fascist yuppies under his breath.

Along with its yuppies, college students, recent transplants, and gritty longtime residents, Missoula sports an increasing population of folks who have found themselves without a fixed address. Caught in the pervading wave of gentrification, many downtown businesses, especially the popular bars and eateries that prefer inebriated patrons to downtrodden panhandlers, are lobbying to have the shelter moved out of the city’s business hub.

My job as development director involves casting a light on a largely marginalized and dehumanized population by writing grants and letters of appeal that advocate for the practical needs of said population; the supper-line shifts and the shared meals help me give voice to the residents and their journeys. To that end, I sit down next to Carl and chat him up about the fishing in Wyoming. I tell him I have a good friend ranching near Crowheart, but Carl is sore at me, I can only assume, for letting Sonja have the last word.

Guilty as charged, I fork into my mouth some browned lettuce got from the expired rack of a local supermarket and soaked in Italian dressing donated from the same, struck by how dystopian my utopia must appear—nearly fifteen percent of Montana residents live below the poverty line—to some of the shelter’s clients. I look out the window toward the river. Nearby the Clark Fork slides glassily by the abandoned Burlington Northern trestle, beneath which, in the midsummer shade, a healthy pod of native cutthroat trout often rests—as does, just ashore, the occasional person sans abri.

The only way to make sense of the suffering of others is to assume responsibility for them, my dad once said, quoting, I’d later learn, Dostoyevsky. He used the line in a dogged argument with my mom about whether he should be allowed to continue teaching classes at the high-security state penitentiary in Jackson, Michigan, where he was earning credit toward his master’s degree—and where an inmate-on-inmate murder had recently occurred. The walls and doors of our old apartment were thin, and when the yelling finally subsided, I gathered that my dad had yielded to my mom on the matter. This dispirited me because I knew he took pride in his service, but also because I thought him tougher, more masculine, for his work at the prison.

The eldest of three, he formed his sense of familial and social responsibility against the odds of his upbringing. His own father, Roman, had followed General Patton into the Battle of the Bulge and returned home to Detroit with a stitched-up chest wound and a profound fondness for vodka, which he self-prescribed per generational norm as a painkiller. Later, Roman worked as a journeyman pipe fitter and fell so irretrievably far down into the drink that he abandoned his wife and three children for another family a few towns away. He died an impoverished alcoholic.

I think of my dad’s inevitable fears of parenthood, which must, somehow, be conflated with my own. Given the trauma of abandonment and abuse, both physical and mental, that he’d experienced at the hands of his own father, he couldn’t have been completely at ease with the notion of becoming a dad. And yet he stepped into the stream. Previous genetic lines, with their potential to transmit latent psychological and physical calamities, have long struck me as compromised, polluted feeder streams that downriver lines can’t help but absorb. How if ever can these tainted headwaters be reconciled when it is said that trauma experienced in a one generation requires three generations of healing before it can disperse, on a cellular level, from the genes?

To his credit, my dad rarely tests, beyond the occasional beer, his hereditary tendencies. He shaped his own journey, to say the least. After obtaining conscientious objector status vis-à-vis the conflict in Vietnam, and following two years in community college in Detroit, he moved seventy miles west to finish his studies in another flagging automobile town, Lansing, where eventually I was born.

Though we could never afford cable TV or more than one pair of new jeans per year, my childhood was peppered with volunteer hours at soup kitchens and detours into grocery stores to purchase food for someone on a street corner who had asked for help. In a stable childhood, though, perhaps it’s de rigueur to desire the pop heroic in one’s parents; in my case, I longed for my dad to be Lance Parish, catcher for the Detroit Tigers. What I’ve just begun to glean of his example, though, is that to lend everyday help to an everyday human being requires the exertion of a less glorified muscle, the brain, specifically the anterior insular cortex that allows a human being to relate empathetically to the experiences of others.

After years of study, he earned his doctorate and became a psychologist specializing in repairing broken families and, whether intending to or not, made empathy his business. As one of my dad’s graduate school advisers, well versed on his background, remarked, “You’re trying to change the course of a river. Be patient.”

After clocking off from the shelter, I walk past the Depot Bar and the Silver Dollar, past the graffitied railcars and old granary turned office space, and turn, teeth chattering, toward home. I trace the river’s slightly downhill trajectory through the valley, the floor of which was once, fifteen thousand years ago, that of a glacial lake. Some mornings, when fog envelops the floodplain, one can imagine the vast and frigid body of water that covered roughly three-thousand square miles, engulfing all but the highest elevations.

At the end of the last ice age, when the Cordilleran Sheet shifted and a twenty-story-high ice dam finally caved, the river flowing from the outlet toward the ocean—a twelve-hundred-foot surging wall of water—was equal in volume to sixty Amazon Rivers. Over centuries, this dynamic geological process repeated itself dozens of times before, as the climate warmed, the ice dams stopped forming and the lake floor began to stanch. The floods left few remnants beyond fossilized seaweed and billion-year-old mud, and as the subsequent glaciers rasped through the land, honing peaks and sculling valleys, life was scarce.

Geologically speaking, the four-legged creatures were soon to follow: ground sloth, mammoth, short-faced bear. By several centuries these and other mammals predated the initial bands of northwardly advancing humans, tribes of hunters. Later, the first people to reside permanently in this valley, the semi-migratory Salish, cohabitated in teepee camps near the confluence of rivers and, except for the occasional scrape with neighboring tribes, lived largely unperturbed, subsisting on plants and berries and camas root, on deer and moose and elk, and on stores of bison they harvested on their annual excursions to the prairie.

Apparitions, helixes of dust, notes of blurred relief on the horizon, a succession of advancing Europeans soon focalized: first the largely amiable French-Canadian fur trappers, some of whom intermarried with the tribe; then squads of diligent, self-important, state-sponsored explorers; then the cavalry-backed settlers, the claimers of land.

For going on two centuries, the West has been fraught with what one writer called “the hallucination of innocence,” the flawed view that vast parcels of undeveloped space, access to prolific wild game, and troves of wilderness simply conveyed a sense of freedom, constituted a blank slate. Of course, such a notion ignores blatant appropriation, waves of displacement, prolific bloodshed, and the ghosts of violent conquest: the lingering truth of what we don’t always acknowledge but nonetheless navigate like a moist, heavy air.

The last light winks out above the Bitterroots as I close in on our new house, a bungalow on the industrial side of town for which we swapped our foot-of-the-mountain rental. Like our old digs, this simple craftsmen build has two bedrooms, but we can paint the baby’s room whatever color we wish because we own it, or pay toward the note, as the saying goes. When we signed the mortgage, our loan officer asked if we didn’t want to “tack on an equity line, bring home a little extra cash” to fix up the kitchen, adding that, with home values escalating in the valley, we’d be able to refinance the house in six months easy, absorb the credit line “no prob.”

His name was Rob, and since he responded to each of our queries and requests with that phrase, we nicknamed him “No Prob Rob.”

“Sure,” we answered with matching wide-eyed looks: What expecting parents with a new house payment and substantial student debt wouldn’t want some breathing room in an otherwise airtight budget?

“How’s five thousand?” he asked, pausing to mute the ringer on one of his two buzzing cell phones. Clearly he was born to negotiate the current boom in real estate; if he had been born in 1860, he would have been selling timber, in 1910, stakes in mines. “Or we could make it ten? Hold on, I have to take this call.”

“You can do ten?”

“Hold on,” he said to the caller, placing his palm over the phone, then said to us, “Of course. No prob.”

Accounting for the more dependable contribution to our collective income, Mary teaches kindergarten. Like many folks in the booming New West, where the cost of living is rapidly outpacing wages, and where underemployed master’s degrees abound, I work a few jobs after the guide season comes to a close, teaching composition classes at the university, working as a poet in the schools, and writing grants for the shelter.

Although we swapped our monthly rent of seven hundred dollars for a nine-hundred-dollar adjustable-rate mortgage and traded the mountain trailhead at the end of our old street for a convenience store, we were soon endeared to the broadened view of Mount Jumbo, the weathered northernmost slope of the Sapphires some local in the 1800s named for its resemblance to Ringling’s famous pachyderm.

Covered in a fresh skiff of snow and lit by a waxing crescent, the slope is remade in miniature in our bed as Mary’s sheet-covered hip. She reclines to read, hand on her stomach, the picture of contentedness.

__________________________________

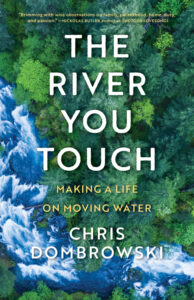

Excerpted from The River You Touch by Chris Dombrowski with permission from the author and publisher, Milkweed Editions. Copyright 2022, Chris Dombrowski.