Lessons of Staying Put from a Southern Childhood

Allison Moorer on Growing Up With Her Sister in Alabama

Sissy and I didn’t talk about it much. We certainly never mentioned anything about what went on inside of our house outside of our house. What could we have said about all the trouble anyway? We were children trying to make sense out of something that made no sense. We were children just trying to get through our days, as everyone does, adapting to this or that, constantly adjusting ourselves to the current state. We bore it like a weighted blanket that provided no consolation, calm, or contentment, only the grave heft of what was.

I think we’d both have done just about anything to change what was happening between Mama and Daddy, but we must’ve known we didn’t have any power beyond our well-honed distraction techniques. I would find out later that Sissy was a counter too, mostly of her footsteps.

Our parents, of course, were the common denominator in our lives. But we had music too. We were surrounded by it. We both sang before we could really talk. I didn’t understand until later how special it was, and that not everyone could sing three-part harmony and find their part by just listening to a few notes. I didn’t understand until later that not everyone’s Daddy had a reel-to-reel tape recorder set up in the house to capture us singing at every opportunity.

Those are sweet memories. I loved going over to the singings at Nanny and PawPaw’s house. Nanny would put the word out and everyone would gather to eat and drink, socialize, and ultimately congregate in her den. Most of her 13 brothers and sisters could play at least a little; some of them could play quite well. Her brother Clyde had perfected a great G run on the guitar and sounded at least a little bit like Jimmie Rodgers. Her brother David had a booming baritone. Gene, her third brother and one of the youngest, had a gorgeous voice but he lived over in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, with his wife, Rachel, so they didn’t get over to the singings very often, but it was a delight when they did.

Most everyone could sing a part or two and they had their own language about doing it. If someone got on someone else’s part they were called a “wanderer,” and to protect your part you were told to “grab it and growl.” When their house burned down during Nanny’s childhood, she said the main things they were worried about saving were the old guitar and the records that her daddy always somehow found the money to buy.

“Come here, meat, let me beat ya.” What a thing to say to a child, but we knew Mammy meant she wanted to love on us. We’d go over to her chair in front of the wall of windows in the den that looked out over the driveway and the two-lane road and sit in her lap awhile. She’d rock us back and forth and talk. Mammy had a biting tongue, but that was only because she was as smart as a whip and saw through bullshit like it was a glass of water.

She simply had no patience for it. She was also generous and loved us, though she only saw her way to doing it by saying things like “let me beat ya” and buying us the school clothes we needed every fall plus something special every Christmas.

Sometimes I’ll do or say something that’s exactly like her and I have to laugh.

Everyone we grew up around was so definite. There wasn’t much wishy-washiness in any of our folks, not like there is in most people these days. Most people you meet now are spoiled for choice, so they end up making exactly no choices and just float around on the wind, going wherever it takes them. It must be miserable to have all that lassitude hanging about you.

Sissy and I never got to be wishy-washy when we were little so we’re not like that now. We never got the opportunity to not know something, so not knowing something now makes for extreme discomfort. I intellectually know that sometimes you just don’t know. But “I don’t know” was never an acceptable answer when we were children.

We were country people. We would spend full days out in the pasture, riding around in the truck, exploring the woods, going down the creek in the canoe, or swimming in it when it was hot. Sissy and I learned to swim in Dry Creek, what we called a particular part of the Santa Bogue that ran through the Moorer acreage. One of Daddy’s favorite things to do was to pick us up by one arm and one leg and throw us out into the water so he could see if we could swim. He got a kick out of it.

That’s how he knew to teach us and it’s how we learned, despite his having been a lifeguard at the Jackson pool one summer. He swam beautifully. I think of noticing then how the water would roll off of his oily, beautiful olive skin in perfect beads. I thought he could and would do anything. His recklessness scared Mama to death. She thought you shouldn’t go in the water if you didn’t know how to swim and to my knowledge she couldn’t. Daddy thought you’d never learn if you didn’t.

Sissy once emerged from Dry Creek with a bleeding head because he threw her in the wrong direction, right into the part that had a rock bottom. She probably needed a few stitches but she didn’t get any. Daddy just doctored her up with a liberal dousing of merthiolate. He thought merthiolate could heal just about anything so he’d always try it first before any other treatment.

Is it only my memories that make that place feel like I see snakes in my peripheral vision?

We spent our childhoods with pink streaks on our arms, legs, or any body part that could get bitten, scratched, or knocked open, and Lord, did it burn when he’d put it on us. He’d probably have made us drink it if it weren’t downright poisonous and loaded with mercury. It’s been banned by the FDA for nearly 20 years now.

Dry Creek separated two parts of the pasture, and if the water was low enough—and it usually was, hence its name—we’d cross it in the truck. Sometimes there’d be washed-out places we’d have to dodge, and sometimes we’d get stuck and Daddy would have to go get the tractor to pull us to the other side.

The tractor stayed at the barn, which was about a mile away from the spot where we crossed the creek. But Daddy would walk to it and drive it back to rescue his truck. If Mama wasn’t with us he’d put Sissy behind the wheel to steer as he towed us across with a chain he’d hook onto the front bumper, the other end hooked to the tractor. Then we’d follow him back to the barn so he could return the tractor to its proper place. He believed in putting things back like you found them. But only things.

One Saturday afternoon we were driving through the pasture, headed home after being out in the woods all day. When we drove by a little swamp that we’d passed probably a thousand times in my life alone, Daddy saw an alligator camped out on the edge of it, sunning itself. Daddy stopped the truck, grabbed his rifle, and shot the gator right in the head. When the bullet struck, the gator headed for the water.

Daddy, never one to waste an ounce of meat or an inch of hide, ran to the swamp and jumped in on top of the reptile, wrenching its neck back, Tarzan style. He strangled the last breath out of the long, mossy-colored creature and dragged it to the truck. He beamed as he announced we’d be eating alligator tail for supper that night.

We lived simply, despite the madness that swirled around our family. Had it not been for that simplicity and our grandparents I’m not sure we would’ve had much grounding. That’s not to say that our parents didn’t teach us right from wrong or valuable lessons to carry into our adult lives—Sissy and I both ended up with a strong sense of decency in most things, but some of that was passed down through others.

I used to get a black mark under my right thumbnail from shelling so many peas at Mammy and Dandy’s. We’d sit at Mammy’s feet in the den in the deepest part of summertime, air conditioner humming when it got above 85 degrees. Mammy would only turn it on when the weather got too hot and humid to bear—she said she hated the sound. Ceramic washtubs would be set on the floor for the shelled peas, and five-gallon buckets full of the ones Dandy would’ve brought in from the pasture garden that morning held the work to be done.

The purple hulls were my favorites. I’d run my hands through the shelled ones, taken by their waxy surfaces—green with what looked like little bruised places for eyes—and the way they sounded when I’d pick up a handful and slowly let them fall back into the washtub—like a hard, faraway rain.

I long for that way of life, so distant from the one I now have. The idea of growing a garden and eating what would come out of it appeals to me now more and more as I grow older. Everyone we knew when we were growing up had a garden. We did too, right by the fence that separated the side yard from the pasture where the pond was. I’m not pleased when I think of all of that artful and practical knowledge dying with my parents.

I’ve grown a tomato plant or two in a bucket and Sissy has done the same, but we don’t need to feed anything with the bounty but our spirits. We don’t really ever plant ourselves when it gets right down to it, not exactly preferring peripatetic lives but finding no reason not to live them. I wonder where we’ll eventually land, if we’ll ever make any place permanent.

Home is not a place, is it? I’ve read that sentence over and over in book after book.

Frankville was home to us, and it was for a long time. It isn’t now. The few times I’ve been back since I left Alabama for good have felt like being in a dream where that so-specific, so-utterly-warped atmosphere takes over my body. What causes that feeling? Is it only my memories that make that place feel like I see snakes in my peripheral vision? Is it my questions about what happened there? Is it just trauma? Our story is made up of memories just like the story of every family. Some are good, some are bad. Some make me break out in a sweat and my head spin even today, even though they have all of these years on them.

__________________________________

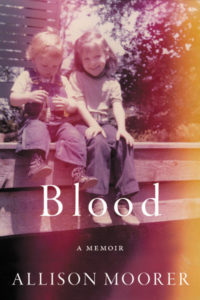

Excerpted from Blood: A Memoir by Allison Moorer. Copyright © 2019. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Allison Moorer

Allison Moorer has been nominated for Academy, Grammy, Americana Music Association, and Academy of Country Music Awards. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing and lives in New York City and Nashville. allisonmoorer.com / @1allisonmoorer