Lessons Learned from a Year Listening to the Fictional Octopus in My Head

Shelby Van Pelt on an Unlikely Friend and Saying What You Mean

I can pinpoint the day when my brain was officially infiltrated by a fictional octopus.

Early in the pandemic lockdown, I sat at the kitchen table with my toddler, attempting to harpoon an avocado pit with a toothpick. Suspended in a glass of water, the humble pit would supposedly sprout into a tree. A science lesson, via Pinterest.

Just as the toddler was starting to slink under the table and sneak back toward the TV, I landed a satisfying jab in the pit’s flesh. “YES!” I vaulted from my chair. “PIECE OF CAKE!”

In an eyeblink, both of my young children were tableside, looking hopeful. “Cake?”

“No. Piece of cake. It means something is easy.”

“Why does it mean that?”

“It just does.”

“Because making cake is easy?” the toddler suggested.

“Well, no.”

My older child, a sharp-tongued kindergartner, took over the interrogation. “Because it’s easy to slice cake?”

“No,” I said. “Not really that either.”

“Remember how daddy’s birthday cake smooshed apart when you tried to cut it?”

I pinched the bridge of my nose. How could I forget?

“Daddy’s cake was a giant cluster,” the toddler giggled, parroting my remarks from that day.

The kindergartner remained focused on the original line of inquiry. “I don’t get it.”

“Sweetie, it’s just a turn of phrase.”

“What’s a turnip phrase?”

He was now living in my head. Giving me unsolicited parenting advice.I plastered on a smile. “You know what? Forget it.” I shoved the avocado-glass aside. Water sloshed onto the pile of worksheets and coloring pages I’d printed out in a futile fit of optimism that morning. “Let’s bake a cake instead.”

Then, I heard it.

Life would be easier if you just said what you meant. It wasn’t the first time I’d noticed this acerbic voice in my mind, but now, it dawned on me that this was Marcellus. A snarky giant Pacific octopus. The narrator of my work-in-progress novel: a notoriously literal interpreter of language and a merciless arbiter of human behavior. And he was now living in my head. Giving me unsolicited parenting advice.

Shut it, herring breath, I thought, tearing open a box of Betty Crocker Super Moist Devil’s Food that I’d fortuitously tacked onto a recent grocery order.

*

As a writer, I love metaphors and turns of phrase. Certainly, literature is richer with them. Always saying exactly what we mean, using the most efficient language, would be dull, tedious. Boring.

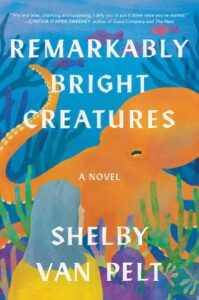

Dull, tedious, boring. In my novel, Remarkably Bright Creatures, that happens to be how Marcellus describes humans. The further I progressed in my manuscript, and the longer I spent with my octopus-narrator, the more I caught myself viewing humans through his lens. And the more I found myself exasperated by human behavior, including my own.

I never set out to write a book about humans. Quite the opposite. I invented Marcellus after watching online videos of octopus escape-artists. I simply thought they were funny. Like, he really wants out of that tank. Probably raging at the bumbling folks trying to stop him. There’s a character in there.

But as I immersed myself in that character, I started to understand that writing from an animal’s point of view, anthropomorphizing as we can’t help but do, isn’t about the animal. It’s about seeing ourselves with fresh eyes.

With increasing frequency, Marcellus’s hot takes would pop into my head.

I never set out to write a book about humans.I’d grouse about having no clean socks and I’d imagine him pointing out my overflowing hamper.

I’d don workout clothes only to ignore the yoga mat and dumbbells in the corner, and I’d see him shaking his head (well, his mantle, technically).

Once, in the thick of an impasse over a takeout order, Marcellus slid in to remind me that no matter how weary I was of dealing with dinner, shrugging isn’t helpful communication. If you want tacos instead of pizza, he scolded, then say so.

That one skewered me. Life would be easier if you just said what you meant. Apparently, this wasn’t only about confusing my children with figures of speech.

Marcellus’s tough-love missives might seem reductive, a black-and-white response to complex psychological and emotional circumstances, particularly in the middle of a pandemic. And they were. I mean, anyone who has ever purchased a piece of exercise equipment and watched it gather dust can attest that it’s more complicated than just doing it. Sometimes we get unmotivated or depressed and let the laundry pile up and then grumble at the injustice of having no socks. We dread the daily dinner doldrum. And that’s okay.

But for me, in mid-2020, I found myself in a state that was not particularly healthy. Having Marcellus gently ruffle me from time to time, almost like a therapist, helped me realize how unlike my former self I’d become.

And, as I came to understand, his missives weren’t always condescending. He lifted me up, too.

When the social media doom-scrolling got out of hand, it was Marcellus who nudged me to delete that particular app.

When I fumed over how others were behaving during lockdown, it was Marcellus who reminded me that my anger would accomplish nothing.

Having Marcellus gently ruffle me from time to time helped me realize how unlike my former self I’d become.As 2020 churned on, I wrote with ever more urgency, finally closing in on a finished, polished manuscript. On the corner of my laptop, I had this handwritten Post-It note: You write. Therefore, you’re a writer. At the time, having published next to nothing, rejections hitting my inbox at a steady rate, I was quite insecure about my writerly identity.

I thought Marcellus would have approved of my note. He is very literal, after all, and that note was the definition of reductively, almost absurdly, literal. And yet, when I imagined him seeing it, he told me to trash it. Rolled his eyes, even though that’s not possible for an octopus.

Why, I pictured Marcellus asking, do you need a piece of paper to tell you this?

I crumpled and tossed it.

*

These days, Marcellus visits my internal monologue less often. I sometimes wonder if that’s because I’m no longer actively creating him, or because I’ve grasped his lessons. Most days, I have clean socks. When I want tacos for dinner, I say so. My children still don’t understand every turn of phrase, but at they’re back in school, at least.

The avocado pit languished. It sat for months upon months, growing slime, but not a single root sprouted. Finally, the kids agreed to discard it, pending my toddler’s request for a backyard burial. I expected Marcellus to make himself known during the service with a cutting comment about futility. Low hanging fruit, no pun intended. Obviously, it was an ill-fated experiment. We live in Illinois. Not exactly avocado country.

But, for once, Marcellus was silent.

Having my animal narrator with me through a difficult season of life was a gift, and I’m fortunate to have chosen a giant Pacific octopus for the job. If any creature on earth is intelligent enough understand humans better than we understand ourselves, it’s probably an octopus.

Sometimes, I miss Marcellus. And I still struggle with writerly confidence. When drafting this essay, I flailed for a while. Then, sitting at my laptop one night, a familiar, curmudgeonly voice nudged me. “You are a writer, are you not?”

Yes, I am.

______________________________

Shelby Van Pelt’s Remarkably Bright Creatures is available now from Ecco Press.