Lessons in Teaching: When Your Student’s a Better Writer Than You Are

Elyssa Friedland on the Professor as Coach

It’s mid-March, freezing and gray outside, and my contemporary novel writing students have just turned in their midterm papers. It’s my second year teaching this course at Yale, my alma mater, and I’m enjoying the semester far more than I thought I would. Even though we’ve been relegated to a Zoom classroom, which I teach from my office in New York City, and they join from either dorm rooms in New Haven or their homes across the country, I feel connected to this group. They are bright. They make interesting observations about the novels we read for craft and ask challenging questions. They show up to class and keep their cameras on the whole time. Expectations in an online classroom are low, but this crop of students makes me glad I signed on for another semester.

So far, all I’ve read of their writing are short pieces I assign for homework. Write a scene where a person nothing like yourself is trapped in an elevator. Journal as if you’re a character in a novel you’re writing. Write a complete story in 100 words or less. The assignments that are turned in to me weekly have been a pleasure to read and mark up. I take my time with each piece I review, using track changes to show where a sentence is rambling, where a generalization should be converted into concrete detail, where the cadence feels off. Even if they don’t have aspirations to become professional writers (only a few of them do), I believe my suggestions will improve their communication in any future profession. Even their texts, tweets and TikToks will pack more punch if they take my sage, professorial advice.

For the midterm, I’ve given them a rather imposing task: Write an additional chapter of A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan’s ridiculously intimidating, compulsively readable, spiderweb of a novel that weaves together so many characters and timelines that I imagine she must have converted her entire writing space into a whiteboard covered in movable index cards to keep everything straight. Or maybe she’s just a genius. Or both. Because all the whiteboards and index cards in the world wouldn’t enable me to write Goon Squad. And now I’ve gone and asked my students to write a new chapter into the book. Maybe I’m emboldened because they can’t protest in person that it’s too difficult.

I have 17 students this semester. The university suggests that writing seminars be capped at fifteen, but I can’t turn down these kids begging for entrance to my class with passionate personal statements about why this course is what they need to round out their Yale education. The flattery works. I go against my better instincts and accept an additional two students, which means I have 170 pages of midterm meat to work my way through.

The first eight papers are strong. I marvel at how multi-talented these kids are. Some of the best midterms so far have come from pre-med and computer science students. They want nothing to do with the life of a professional writer (and who can blame them?) and yet still their words dance off the page. They get As that I award easily and without too much concern that I’m going soft in my old age. I offer my usual commentary, but with extra attention to narrative structure. I suggest where a reordering might have been effective. I ask the students to question if their opening scene is really the best entry point into the story or if their POV choice was optimal. In other words, I’m doing my job and I believe I’m doing it well.

And then comes the ninth paper. I’m getting tired, my eyes are watering and the computer screen is giving off a halo. I open the document even though I know I’m better off starting fresh the next day. Except this is paper number nine, and if I can grade this one today, then I’m more than halfway through my stack of 17.

My student’s raw talent might surpass my own, if this particular assignment is any indication. But that doesn’t mean I don’t have a valuable role as a “coach.”

I do my usual when I start with a new paper. I resave the file with my initials attached to the document name and I turn on the track changes feature. I read the first sentence. It’s ambitious, I can tell already. Second person POV. Yikes. Egan can do second person; so can Bret Easton Ellis. But my student, a babe in the woods? Maybe I should have called it a night.

The paper starts with a scene at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a setting I know well from my actual life. I relax a little, feeling myself at ease in the fictional world my student has created. I read on. It’s not until page four of the ten-page paper that I realize my fingers haven’t moved except to scroll to the next page. I haven’t clicked once on the “add comment” button. I haven’t deleted any phrases or asked my student to reconsider the inclusion or omission of a particular detail. Because I’m mesmerized. I’ve fallen down the rabbit hole of this story, I’m Alice in the wonderland of an incredibly crafted fiction piece. I don’t feel like a teacher at all. Reading this midterm, I’m nothing but a reader who is lucky enough to be seeing these pages. My student isn’t quite the published Egan, but she’s maybe Egan at an earlier draft.

The paper finishes as strong as it started. I’m filled with a rare mixture of emotions. Elation to have experienced reading such a strong piece of literature. Shock that a voice so convincing could come from a writer of just 20 years of age. Jealousy, too, because I’m certain I couldn’t have produced this quality of writing—and certainly not while juggling three other demanding courses. And finally, uncertainty, because what can I offer this student who has surpassed my abilities?

I shut my laptop and climb into bed, but sleep feels impossible. While I’ve had talented students in the past, their work has always had an amateurish quality to it, appropriate for writers who are at the beginning of their practice. I know I’m not the best writer out there. I only need to reread Goon Squad and the other novels I assign my students (Less by Andrew Sean Greer and There, There by Tommy Orange) to be reminded of this fact. But I’ve always been better than my students. Not better than what they will eventually be—but better than they are now. And, suddenly, I’m not.

My husband is serendipitously watching the Tiger Woods documentary in bed. I’m grateful for the distraction and watch as Tiger’s father coaches his five-year-old wunderkind. It’s not too many years before Tiger can beat his father, but he remains his coach regardless. It reminded me of reading Andre Agassi’s memoir, Open, a few years earlier. His father was also his first coach. The coaches that followed the senior Agassi were all critical to Agassi’s staggering success. Andre could have beaten all of them easily.

My student’s raw talent might surpass my own, if this particular assignment is any indication. But that doesn’t mean I don’t have a valuable role as a “coach.” I went back to this student’s paper refreshed the next morning. Upon a second close reading, I found places for improvement. They were there the day before, of course, I had just been too stunned by the depth and range of the piece that I hadn’t been able to concentrate on editing. This time around, I highlighted the words that felt awkward. I cut extraneous dialogue. I suggested a different ending. And I slapped an A+ on it when done.

We were coming up to the class on revision in a few weeks. Normally I have the students revise a piece of their own writing. This time, I decided to have my students tackle revising the first three pages of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, smiling that its title was practically begging to be the guinea pig for this exercise. Working in breakout rooms, my inexperienced writers made ruthless edits to the opening scene, many of which I agreed with. We had a good chuckle over Franzen’s use of the word “zoysia” in the seventh sentence of the book, leading to a class refrain we used for the balance of the semester: #justsaygrass. We Edward Scissorhandsed a paragraph describing a repeating bell sound that could have been rendered in a single sentence. Could we have written The Corrections? Maybe if we combined our brainpower. But that didn’t mean we didn’t have valuable criticism.

At my 15-year Yale reunion, I attended a reception where the Dean of Admissions spoke. His name is Jeremiah Quinlan—he was a member of my same class. Joking, but not really, he told his fellow graduates from the Class of 2003 that none of us would have gotten in today. Having just read The Meritocracy Trap by Yale Law School professor Daniel Markovits, I see what Quinlan means. It’s a whole new level of competition at the top. I will read more midterms and final papers that surpass what I can do. But that doesn’t mean I’m done teaching.

I will continue to track change my students’ work to a higher level. But there’s a second part of my job. I’m a coach, as well. Every writer will face writer’s block and the sting of rejection. Every writer will feel vulnerable sharing their words. I can encourage my students to keep going, to stare down the blank page, and to frame their rejection letters at the same time that I’m reminding them, for the thousandth time, to “show-don’t-tell.”

And, while I may have needed to look up zoysia, I will always be able to comment #justsaygrass.

________________________________________________

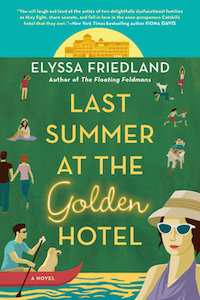

Elyssa Friedland’s Last Summer at the Golden Hotel is available now via Berkley Books.

Elyssa Friedland

Elyssa Friedland is the acclaimed author of Last Summer at the Golden Hotel, The Floating Feldmans, The Intermission, and Love and Miss Communication. Elyssa is a graduate of Yale University and Columbia Law School and currently teaches novel writing at Yale. She lives with her husband and three children in New York City, the best place on earth.