Lessons in Humility From Teaching in the Mojave Desert

Thomas Maltman Remembers His First Year As a Middle School Teacher

During your first year of teaching, a plague of grasshoppers invades the Mojave Desert. When you walk from the mobile home classroom where you teach an unruly crew of seventh grade language arts students and cross the black tarmac of the basketball courts, dead grasshoppers crunch under your loafers. You watch in dismay as one of the boys swallows a live grasshopper whole on a dare from classmates. This is not the worst thing that happens that year.

Some of your students have grown up poor, so the lunch the district provides may be the only square meal they get all day. That first year, a black widow spider creeps from the dirty collar of one boy’s shirt and crouches there, fat and poisonous, near the pulse in his throat. You freeze, but the girl behind him smashes the spider with her bare hands. When you use a Kleenex to pluck the crushed corpse from the shag carpet, the boy looks at it, shrugs, and goes back to his grammar book. Neither child comments on the matter. That’s not the worst thing, either.

In this district, a tracking system insures all the best students go next door to the experienced teacher and the rest come to you. The students know this. They call themselves your “castaways” on good days, and on bad days they set thumb tacks on your chair when you’re not looking, but some teachers have it worse. You’re there in the staff lunchroom when the band director has a nervous breakdown. Another day you finally get up the nerve to ask that one teacher, a former army drill instructor, where the jagged scar running down her cheek comes from. “Brown recluse spider bit me,” she says, “down at Camp Shelby, Mississippi.”

One of these kids is named Michael. You learn early on that his father died, and you understand why he looks up to you, so you want to be a kindly presence for him, the older brother he doesn’t have. But when his mom’s newest boyfriend is murdered right before his eyes, right on the front lawn, Michael changes. He goes from being one of your top students to one of your worst tormentors. Daily you kick him out of the classroom, until one day he just stops coming. The special education advisor counsels you: “You can’t save them,” she says, “sometimes you just have to let them fall.” Maybe this is the worst thing, you think, the scene they don’t show you in the bogus inspirational movie where the teacher saves everyone.

Somehow you make it to summer break and you’re pretty sure you’re going to quit before the second year starts. You spend weeks with cousins who live near the beach and you take up bodysurfing. You bleach the tips of your hair and grow a goatee. It’s the 90’s, dude. Before you can quit the second year is already starting and you’re in the thick of it, but something is different now. You have bleached tips and you surf. Without any planning on your part you have become the cool, young teacher, a reputation you don’t deserve. You’re teaching all the same stuff, but you teach it with confidence now. Listen, you hated the desert when you lived here as a student long ago and your dad was a pilot at George AFB. You hated middle school, the worst time in your life, and now you teach in a middle school in the middle of the Mojave Desert. But you know what? You love the stories. You love the words. You love the poems and the songs that give meaning to our struggles. Some of that love comes through in the fumbling way you teach. Plus, that hair, dude. It’s really hard to hate someone with nice hair.

The special education advisor counsels you: “You can’t save them,” she says, “sometimes you just have to let them fall.”

All along you have this crazy dream to write a novel, but you don’t know how such a thing is possible. Your job overwhelms you during the work week. On weekends, you find the time to write a couple of poems, one on Saturday and one on Sunday, and you send these poems to various literary journals, your goal to collect rejection slips from all fifty states.

You would probably be there still, teaching in the desert, sending out poems on the weekend, but you meet someone, a pastor from Minnesota who also loves books, a redhead with a dream of sharing the Gospel. She also believes in your dream, despite all available evidence telling her otherwise.

What will matter more than any small talent you might possess is your doggedness, the way you latch onto a story or idea and won’t let go until it’s finished. Let’s say you go back to graduate school to hone your craft and find the time to write, and after you graduate you start teaching at the college level. Maybe you go on to publish a few of novels and they do okay. It all comes true, everything you hoped and dreamed, but it’s also bittersweet. Your first novel receives a harsh review in the newspaper that all your friends and family read. Here is your dream, one you spent years bringing into being, and according to the review you are a failure. Yet despite the review the novel will go on to win several national awards and more than a decade later you will get emails from readers thanking you. So what if there is little money or fame, not in any of it? Maybe the rest of your life you will go on doubting yourself, but you also hope you will not let these doubts stop you. You reach the summit, but the oxygen is thin up there, so what can you do but go back down into the valley?

The valley is a good place to remember. It’s good to be humbled, even if it hurts at the time. If you strive to make art, you have to know you will be rejected by publishers, by newspapers, by colleagues and friends, but in the end it’s worth it, because you did it for only one reason: you love the stories. So you take time to remember where you came from because there’s not a day that passes when you shouldn’t give thanks. You’re lucky. Here is the place where you began: The Mojave Desert. Grasshopper plagues and black widows and gang members bleeding out on a patch of yellow lawn. You remember all this, because my God, isn’t this life full of marvels if someone like you sometimes manages to tell the story right?

__________________________________

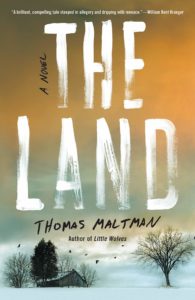

From The Land by Thomas Maltman. Used with the permission of Soho Press. Copyright © 2020 by Thomas Maltman.

Thomas Maltman

Thomas Maltman has an MFA from Minnesota State University, Mankato. His first novel, The Night Birds, won an Alex Award, a Spur Award, and the Friends of American Writers Literary Award. His second novel, Little Wolves, was an Indie Next pick and an All Iowa Reads selection. He teaches at Normandale Community College and lives in the Twin Cities area.